Miscellaneous

-

Profile

published: 23 /

8 /

2016

Adrian Janes finds that the Punk 1976-78 exhibition in the British Library, though by no means exhaustive, succeeds in conveying something of the fraught circumstances in which the punk movement arose in the UK and the excitement and great creative energy it unleashed

Article

On a terminal a rolling display of front pages shifts between reports of mass unemployment (from the days when over a million out of work was thought scandalous, rather than today’s rebranding of a similar figure as “record numbers in work”), and the fallout from the Sex Pistols’ expletive undeleted appearance on the tea-time TV show ‘Today’.

This appearance can be seen on one of the screens that intersperses the exhibition (along with other powerful clips of bands like the Buzzcocks and Siouxsie and the Banshees). It’s striking how the exchanges between host Bill Grundy and the Pistols (as well as a peroxided Siouxsie) are little more than smirking banter with a side order of swearing, Grundy clearly neither impressed nor distressed. But presented next day in the press as an asterisk-laden dialogue, it all came over as much more aggressive and helped to fuel a reputation that meant the majority of the dates on the December 1976 ‘Anarchy in the UK’ tour were cancelled.

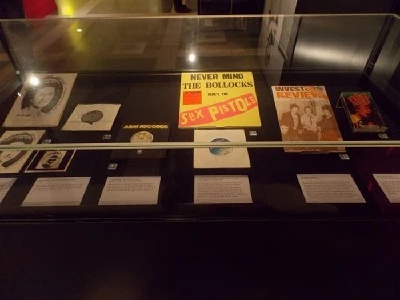

After an initial nod to the Ramones’ galvanising effect, the Pistols’ story becomes necessarily central to the exhibition, given the inspiration both their sound and their look provided to others. The displays include examples of clothing, like the notorious ‘Two Cowboys’ T-shirt, from Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s shop Sex (where the band were initially brought together); bassist Glen Matlock’s resignation letter, signed by all five Pistols (including one John Beverly); and a cover of ‘Investor’s Review’ which celebrates the Pistols as Young Businessmen of the Year, for their legal looting of three record companies’ coffers within twelve months. Musically, this merrygoround is represented by examples of limited pressing or never-released singles, as EMI, A & M and Virgin in turn tried to make “cash from chaos.”

Elsewhere are examples of Situationist literature. Situationism, an outlook which melded art and revolutionary politics, influenced both McLaren’s practice as a manager and Jamie Reid’s work as a graphic designer. Reid used the subversive concept of ‘detournement’ for images like the safety-pin sporting Elizabeth on the sleeve of ‘God Save the Queen’, originally an official portrait by Cecil Beaton.

This reuse and repurposing of existing material was also part of an effort to make an impact with limited resources. For young people with scant cash, this meant customised jumble sale and charity shop clothes. Communication, in a time of three TV channels and before home computers, mobile phones and the internet, was chiefly in the form of fanzines like ‘Sniffin’ Glue’, handwritten or using manual typewriters. Although this was the most famous title, a selection of these publications reveals how rapidly and widely the message and the image spread throughout Britain.

Just the extra physical effort that was needed to get these fiery screeds onto paper and reproduced says much about how ready the young were for something fresh. This new wave of energy among musicians and writers fed punk’s audience and often inspired them to do something creative in turn, which could just as well embrace fields like fashion and film. For example Don Letts, DJ at the first punk club, the Roxy, began his film-making career by filming bands who were also simply his friends. And just as Letts is now an esteemed 6 Music DJ, so the exhibition notes how many of the fanzine writers went on to successful media careers.

Karl Marx, a familiar face within the British Library 160 years ago, can also be glimpsed provocatively stitched into a Pistols’ shirt in one of the video clips. But punk was important in seriously politicising many. A picture of members of Steel Pulse and the Clash demonstrating together outside the house of Martin Webster, a prominent leader of the fascist National Front, and a letter to the music press which helped to launch the Rock Against Racism campaign, recall a time when the NF seemed to have the same malign potential as its present-day French namesake.

Women aren’t massively represented - to Viv Albertine’s signed chagrin, on one of the exhibition panels - but one screen shows an interesting extract from a film called ‘Stories of the She Punks’. This features recollections of the liberating impact of punk, from members of bands like the Slits and the Raincoats. A large picture of Poly Styrene in some sort of rubber ensemble is seen elsewhere. I’d suggest that it’s space constraints that are chiefly responsible for any apparent neglect: in terms of popular impact, arguably the Clash and the Damned should also be better represented than they are.

At the end, in the same space as the fanzines is a wonderful display of picture sleeves from one hundred punk singles: a listening post allows you to hear a song from each one. Those spiky chords and urgent voices, out of tune rather than Autotuned, still have something to say.

Whether you belong to the Blank Generation or are a bored teenager, ‘Punk 1976-78’ is a short, sharp, salutary shock. It may even make you form a band.

Picture Gallery:-