published: 16 /

6 /

2016

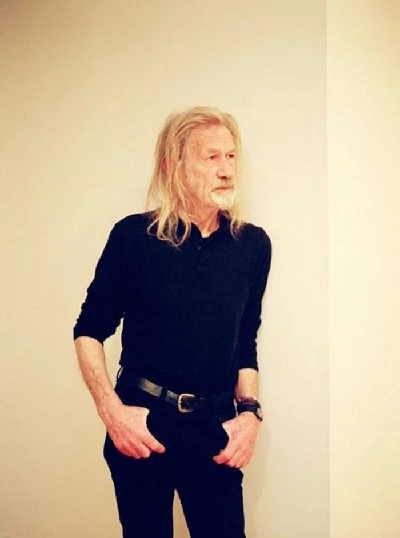

Crass founder Penny Rimbaud talks to Kimberly Bright about his main musical influences

Article

Crass founder, activist, writer, artist, and unlikely English folk hero Penny Rimbaud has spent much of his adult life in the Essex countryside at Dial House, the longest running intentional community in the UK, welcoming strangers and feeding them soup made with vegetables from the garden. While the population of idealists that have come and gone are self-selecting in their polite willingness to get along with others and contribute to the labor of running the place, amazingly only two problematic residents and one guest has ever been asked to leave the commune in its fifty year history. Also amazingly, according to Rimbaud the most often stolen thing from the house’s common area has been copy after copy of Valerie Solanas’ 'S.C.U.M. Manifesto'.

Before, during, and after his time with the influential anarcho-punk band Crass, Rimbaud has been the elder statesman of the counterculture and direct spiritual descendant of the Romantic poets. For someone who has had such an impact on youthful rebels all over the world, to the point where a “Crass punk” is its own specific stratum and veganism is no longer seen as a bizarre fringe lifestyle choice, Rimbaud is an unexpected surprise. Rather than the angry, noisy dissident with a spiky, hard-hitting, anti-authoritarian leftist political message one may expect to meet, he turns out to be a soft-spoken, well-educated, well-read, cultured, confident, erudite hippie country gentleman who happened to come from a privileged background. Rather than use these advantages to his own benefit over the years, he has lived as the equivalent of a philanthropic libertarian British Dalai Lama - or possibly a local hedge wizard. If Prince Charles lives long enough to become king, he could do a lot worse than to take Rimbaud on as his ecological policy advisor.

At 73 Rimbaud’s taste in music is naturally far ranging and eclectic, yet his list of pieces and artists that have touched him the most may come as a shock. “Music itself is a balm for me and the sort of music I listen to represents that balm,” he says. “Whether it’s Górecki’s 'Symphony [of Sorrowful Songs]' or Keith Jarrett’s piano or Joni Mitchell, etc etc. I suppose people ask why I like melancholic music. I don’t think it is melancholic. The deeper spirit doesn’t speak loudly. It doesn’t laugh loudly, and it doesn’t cry loudly. It simply is. I like music which simply is.”

On a recent chilly Sunday late afternoon he was kind enough to come in out of the garden at Dial House, where he was clearing away a shrub that had grown up over the window of his study, to stand uncomfortably in cold, wet work clothes and answer questions about what kinds of music have influenced his life and work. Luckily he took a break halfway through so he could get some dry clothes and a cup of tea.

NEW ORLEANS JAZZ

Rimbaud: I listened to jazz since I was a kid. Before rock and roll I was listening to music before Elvis and Bill Haley and those people who were the first rock and rollers. There was sort of blues, which you could very rarely get ahold of and people like those sort of guys you didn’t hear about over in England. There was a trad jazz scene, if you like, which was very attached to a sort of left-wing [view], the beginnings of the peace movement and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the people whose symbol was the peace symbol which then became widely seen as a peace symbol but actually was originally the symbol of CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. I was never that attracted to trad jazz. I mean, I did listen to it, but I liked the real New Orleans jazz, what I ever heard of on albums, on whatever you call vinyl, or actually those breakable things, on 78 rpm. Really I sort of grew up with classical music and jazz.

SKIFFLE

Rimbaud: I was in a skiffle group when I was about twelve or thirteen. I formed a skiffle group called La Bohème. They did a few gigs. We even got some Teddy Boy following, which was quite an achievement, I can tell you. It might have been because we had a tea chest bass player called Kate Wilson who was extraordinarily good looking and considerably older than the rest of the band. I think that actually the Teddy Boys were rather pursuing Kate than enjoying our music. Nonetheless we got a following of Teddy Boys, which was quite extraordinary, really, considering I came from an upper middle class background and I could be very quickly identified as coming from a different class than these working class kids who weren’t going to take any shit. But they really appreciated what we were trying to do, which was very lovely.

I made a sort of banjo out of an old tennis racket and press. You know those presses you keep rackets from bending on? Maybe they don’t use them anymore, but they used to use this thing you screwed down to stop the racket warping. By stringing stuff around it and bashing it, I made this ukulele banjo sort of thing. I rather badly played that, but I was the singer. We did some Leadbelly stuff. I can’t remember what it was. Sonny Joe [Ivy], Brownie McGhee, that’s the sort of stuff we did on top of the very English version of skiffle, because skiffle grew out of the trad jazz tradition. That was very much a development from trad jazz. I mean, in America it’s jug music, isn’t it, where you play bottles and washboards and tea chest basses.

I don’t know how Kate got into the band, anyway, but she was very nice. We were all quite a bit younger than she was. Maybe she was being Mum. I’m not sure. Dad wouldn’t let me go out. We got some good gigs. We used to do this Marconi Radio Jazz Club which didn’t go out on the radio, but it was the jazz club in the nearby town [Chelmsford, Essex]. It was a big Marconi radio factory. They were big telephone people in those days. There used to be some good audiences and stuff. I had to go in my school uniform. I wasn’t going to be allowed to go out looking like a tramp, as he would put it. So I used to smuggle some stuff in a bag and change when I got out to the forest or whatever so that I could look at least a bit cool by the time I got to the gig. Eventually he stopped me doing it altogether. I was forbidden, I mean, not that that would have stopped me, but the whole thing collapsed anyway. That was the end of my years of skiffle. I suppose we lasted a year and a half or two years.

BRAHMS

Rimbaud: My dad absolutely adored Brahms. That’s one of the few things I inherited from my father, a deep love of Brahms. Brahms was probably the first classical composer I listened to seriously. My tastes headed up to the 20th century, and my father’s tastes tended to go sort of back to Bach and early music. While mine moved progressively and quickly toward modern music, like Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Shostakovich, all of the 20th century greats.

BENJAMIN BRITTEN

Rimbaud: Notably I suppose Benjamin Britten, through his work the 'War Requiem' was an influence. I was a school chorister and a very good one as well. I actually sung in most of the great cathedrals of southern Britain, not in the north. Members of choirs would be selected for big performances in London and I was selected to perform in what I think it was the first ever performance in Britain of Benjamin Britten’s 'Spring Symphony', and he was conducting it. That was my early experience, and I was only nine or ten or something I suppose but being involved with engaged with and working for a 20th century musical genius. He was a lovely, lovely man, he was very warm. He was very warm and humorous and very caring and lovely and it was great working for him. Anyway, that introduced me to Britten.

I think it was ’62 or ’63 he came out with the 'War Requiem', which was the setting of the 'Latin Requiem' text set against the war poems of Wilfred Owen, who was a First World War poet who died in the last week of the war, shot in the last week of the war, whose poems are tragically and passionately sensitive toward youth, really, his deep love of his men. It wasn’t just his men but all mankind. Although he went to war as an officer he very quickly came to understand the madness of it, and his compassion fell on all sides. He wasn’t a jingoistic Back Britain nationalist. He was a humanist. Anyway, that inspired in me a pacifism which was already there in its early stages within my thinking, that the 'War Requiem' knocked home entirely and completely my revulsion toward war and violence. That was a big early one. I guess the top of my album list is and will, I guess, always be Benjamin Britten’s 'War Requiem', because it’s one of the great pure voices of the 20th century, and in that 20th century which was so incredibly engulfed by war, his was such a beautiful plea and cry for peace within that madness on a profound level of people like Gandhi or perhaps on a lesser similar level someone like John Lennon or Martin Luther King. All these people who have cried against the oncoming tide, demanding peace and love and respect, and in the musical sense Britten really hit that one right in the heart with the 'War Requiem'.

After art school I was listening to tons of Benjamin Britten more than anything. I went through all his work, all his operas. My main creative occupation in those days was painting rather than writing. I just had his music playing all the time, like 24 hours a day. I mean, there isn’t anything he wrote that wasn’t involved in some way with the broadening of the human spirit. He was very much a pacifist and gay at a time when being gay was illegal in this country etc etc, so his work was redolent with this desire for a better world. How could we do it? What did the terrible pains we inflict on other people through not doing? I was very drawn to that. I guess really those years when I was pretty much on my own here painting was pretty much imbued with Britten’s work, maybe listening to a bit of jazz now and then. Occasional bit of Beatles or something or other, but it was primarily Britten.

BILL HALEY & THE COMETS

Rimbaud: Looking back, because I was a chorister, because I lived in a semi-musical family in the sense that my father and mother loved music. Dad could reasonably well play the piano and he certainly used to like to play the piano, thumping away, so music was always part of my life. When I first heard Bill Haley it was on a sort of pirate radio station called Radio Luxembourg, which you could listen to on earphones, and that’s where I first heard him. Radio Luxembourg used to play exclusively sort of jazz and blues and stuff as it came over to Britain, which was increasingly happening by the ’60s. Hang on, I’m losing the track here. Oh yeah, yeah, I heard some Bill Haley and thought, “Oh well, this is fantastic,” and so I went to the record store and ordered it, and when I got back home I just got a complete bollocking from my brother and my parents. I was actually really indignant, because actually on the back of 'Rock Around the Clock', or it might have been 'See You Later, Alligator' I can’t remember which one I bought, but on the back of it was 'When the Saints Go Marching In', which of course is an old jazz number, so I just didn’t get it. I was thinking, “What’s your problem here?” It didn’t sound much that good to me, really, just some funky jazz more than anything else. It was “Get that out of the house!”

It was partly a class thing. By then rock and roll and Bill Haley and the early rockers, Eddie Cochran and those people, were all in Britain very heavily followed by the Teddy Boys, who were really the first working class kids who basically said, “Yeah, well, we want a life too,” and they did it by style in the same way as bling. “We want a life. Look at me. I can look good.” It’s a first step toward claiming your own space. So rock and roll even in its early stages would be identified as being potentially a music of revolt or a music of objection or a music of downright cockiness. I mean, it was something people were attaching to say to straight society, “Piss off, get out of my way.” So I think that much of my parents’ and my brother’s reaction to me coming home with some rock and roll when actually not necessarily disliking the music, although Dad loathed the music. It was my brother more than anyone who introduced me to jazz, so I could not understand him disapproving of this new music.

THE BEATLES

Rimbaud: The first time I heard the Beatles was 'Love Me Do', their first single. I was in a bowling alley. I was still at art school, and I thought they were a girl band from Detroit. That’s what they sounded like. Funny, isn’t it? But they really did. They sounded like Mary Wells, people like that I was really into at that time. What we used to call blue beat or now we consider ska music. That was happening then. That sort of stuff like Mary Wells and Dionne Warwick and those people, I was really enjoying that, and the Beatles just had that feel to it. They were sticking to arrangements, but their voices sounded like women’s voices to my ears. My ears pricked up when I first heard that. I thought, “Wow, this is amazing! What’s going on here?” I found out it was guys, they were from Liverpool, and I found that really exciting. There’s something new and fresh. I mean, they weren’t saying anything particularly in those days, but somehow by their very nature they were saying something. Yeah, I was very inspired. They were also working class. Working class kids making a break was big in those days. I wasn’t working class, but I think my early experiences at home and the innate snobbery of schooling and churching and familying I experienced didn’t ring any bells for me. I was in revolt against it. At the age of four or something, I was in revolt the day my father came back from the war. If this is the real world, count me out. That’s why I never have become particularly political with a big “P” because the real world the material world is where politics with a big “P’ belong. Well, I don’t belong in that political mind, because I don’t belong in the material world, at least if what my dad told me was real.

JONI MITCHELL

Rimbaud: Joni Mitchell was the first person I heard who attracted my ears. Joan Baez was a bit too serious for me. I suppose it’s because her politics were very much directed towards the American situation, you know, so they didn’t make so much sense. Although in some respects, there are some similarities between the problems in America and the problems in Britain, there are also huge differences in the way we go about dealing with them. We have a class system in this country which just does not exist in the same form in America. We don’t have the same type of racial differences here than in America, and all of these things are very delicate and very sensitive to place. It’s partly why Crass chose not to eventually go anywhere but Britain, as we found that people weren’t actually understanding or we weren’t understanding the situations that we were talking about.

An example is one occasion we went to Germany to play a gig very early on, and as we were doing the sound checks and things there were masses of kids waiting outside. It started turning nasty. The police turned up in their cars and got out, got out behind their cars with their guns pointing at all the kids outside the thing, and we didn’t know how to deal with it. In Britain we’d have known precisely how to deal with it, because we know the language, we know how you behave, we know what accent to put on, we know how to blag our way through a situation. There we didn’t a clue. You know, what happens if you walking toward someone waving a little white flag? What do you do? I know what will happen here: you’ll be given the space. Given that we were very serious about what we were doing, we couldn’t risk putting other people at risk other than ourselves, you know, to say what we wanted to say.

So, in the end we decided the best thing to do was not go away from Britain.

A lot of what we sang about was very universal. The important stuff we sang about was universal, but it could be very place specific, and on that level it was very difficult. For example, 'White Punks on Dope'. You know, in this country at that time there were a lot of white liberals being rather patronizing and condescending toward the black voice, which was growing fast and also there was a lot of the Left trying to ride on the backs of that protest. So we flew in saying, “Come on, just pull back, if you want a riot, make your own riot, don’t start getting on other people’s trip and that’s fucking it up for them.”

We got a lot of support from black radicals for our stance on that, but what I’m saying is that that would have been a completely different situation in America. The traditions, the backgrounds are so incredibly different. I mean, the black community in Britain they’re not primarily from the slave tradition. The black community in Britain is primarily people who came over in the ‘50s under the lies of being offered great sources of fortune if they did and then finding that actually they were just being used as third class workers, but they didn’t come from slave tradition. They did far, far back when the West Indies were first inhabited or they were taken from Africa, but it didn’t have that long looming history of battle that black America has. That particular song I was using as an example wouldn’t have been applicable or made sense in the American theater.

JOHN COLTRANE: 'A LOVE SUPREME'

Rimbaud: John Coltrane’s 'A Love Supreme', that one stays pretty heavily a favorite. Actually just about anything Coltrane’s done, but that one, for sentiment, I think it’s a very powerful voice. It’s one that really started to bring together sort of black and white alternative thinkers in a big way. Obviously you’d had the peace movement, but that brought in a popular element, of some popular culture element. I note that 'A Love Supreme' was loved just as much by black radicals as it was by white radicals. Yeah, one of the great … points in social affairs. One that possibly hasn’t had the profound effect it should have done. I think on every level it’s a very valuable album in its sentiments: its political sentiments, Its spiritual sentiments, its beautiful balance between the inner and the outer self, which I think is good, just an honest, straightforward plea for love and goodness in the world, which I appreciate.

I don’t find John Coltrane noisy. It’s almost like it’s the blood running through my heart, and I can feel that, and that’s the music that calls me. Stuff that flows through my heart and not through my head.

MODERN JAZZ/AVANT-GARDE JAZZ

Rimbaud: I was always interested by modern jazz, Sonny Griffin. I was actually more interested at that time in the West Coast jazz, Miles, Gerry Mulligan, the cool jazz rather than the fierce bebop, although I loved Parker and people like that, but actually Gerry Mulligan was really big for me. Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker. I thought they were suave.

I really loved Johnny Griffin a lot. He’s sort of disappeared, though. I got more progressively into that whole, I suppose, what we’d call mods’ music. You know, the Beatles were a part of that, people like the Animals. I didn’t much care for rhythm and blues. I didn’t like white people doing blues, because I used to do them when I was a kid in the skiffle band, and it didn’t wash for me anymore. I particularly liked the Beatles, because it was like English folk music, really. It didn’t use blues riffs, and I liked that. It wasn’t ripping off black culture in any way, and I think that was one of the nice aspects of it. It didn’t make any blues reference at all. Again it had that slightly English folk quality about it, which I liked, because it has a purity about it, I guess. I’m interested in that thing in America where people are rediscovering what was known as redneck music, realizing that good stuff from the Ozarks, hillbilly stuff, which is kind of interesting. These new American folk bands. It seems to be a new area of discovery. You know, the Left was so difficult toward white working class attitudes in America, they just sort of ignored their music as being politically unsound. I think that was a sad mistake in a way.

[Performance art group EXIT], that came out of painting. That’s when my paintings became more and more abstract. From being super realistic, I started becoming more abstract, then I thought “Well, I can’t get more abstract enough,” and then sound was the obvious next move. Initially what we were doing was writing scores on graph paper with color and shape, and the shapes represented the quality of sound, the colour with different qualities or weights and things, so it was a visual score. So the first year with EXIT that’s what we worked from, but progressively we worked toward improvisational stuff, partly inspired by American free jazz, people like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp, people like that, but also the Stockhausen Messiah and the great European classical composers.

I was very inspired by John Cage, for example, not necessarily by his music but just by his attitude. I was unaware at the time that he was heavily into Zen, but he was a practitioner of Zen, and I guess that’s what I picked up on.

When I was at art school as a student I used to say what I was looking for was truth and beauty. I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew that’s what I was looking for. It was actually the call of the Romanticists, the British poets who were also on the quest for truth and beauty. I guess it always has been my quest.

People say I was pushing the limits with Crass, but that’s just not true. It may be a very wild cry but it was really just saying “For God’s sake, we must do something. We have to move on. We have to destroy war. We have to learn love.” That’s what it was trying to say in a furious and angry way. Because by then I was getting so frustrated, I’d lost my way. I didn’t know how else to do it. Since then I’ve had twenty years pretty much silently writing in my shed, and had no interest at all in going out into the world. It was only at the beginning of this century that I went back onto the road, if you like, and started talking and reciting poems and getting involved with jazz musicians and performing again. It took me years to find the strength again to find some deeper inner thing that I could take out into the world, because I think there was a sense that we hadn’t really fulfilled our desire within Crass, and that was an unfillable desire, which was to change the world.

GEORGE HARRISON

Rimbaud: I don’t really like much rock and roll now. I hardly ever listen to it. I occasionally listen to George Harrison. I love his album 'All Things Must Pass', and that’s a deeply spiritual album. He wasn’t so much into Zen as into some of the Indian-based philosophies. Nonetheless there are great parallels, and I could identify with that. There was one line of his, “Everyone has choice whether to or not raise their voices.” I think I was about 24 at that stage, I’d been out of school teaching at the art school, and it was just a revelation for me. Just a simple line like that, you don’t have to shout. You’ve got a choice. You don’t have to be angry, that’s saying. You don’t have to take it out on people. Look to yourself. There is no authority but yourself. What I learned from George that came out twenty years later as “There is no authority but yourself.” What he was saying was “Don’t get upset about it. It’s you. Look to yourself first. Look to yourself.” I suppose that’s what I looked for in the music, that immortal quality. I mean, if there is any immortality about human existence which is proven by the fact that we still exist. It exists on love. It doesn’t exist on war or politics. However rigid and stupid and ugly it can sometimes be, we survive. That’s what I always feel. We survive. Some of us don’t, but that’s part of what’s happening. Our job is to do it with all the rich fulfillment of love. There’s no point otherwise. We’re walking on the dead. I know that. I honour them by not being judgmental, not by being critical but by thanking them that they’ve given me this place to be.

'Hot Crass Buns' drawing by Moose Allain

https://twitter.com/MooseAllain/status/713743144202936324

Band Links:-

https://crassahistory.wordpress.com

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penny_Ri

https://www.facebook.com/crass

Picture Gallery:-