published: 14 /

11 /

2014

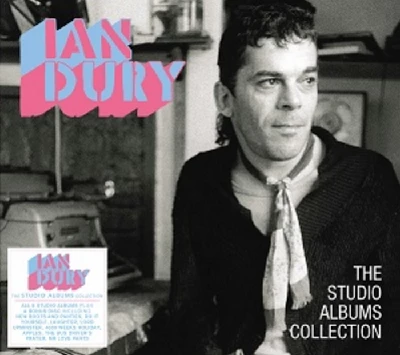

John Clarkson speaks to Mick Gallagher, the keyboardist with Ian Dury and the Blockheads, about his group's history, and a new collection, 'The Studio Album Collection', which brings together all of Dury's work

Article

When Ian Dury died in March 2000 at the age of 57, rock music lost both one of its greatest lyricists and most colourful characters.

The crippled North London–born Dury, who had contracted polio at the age of seven, came to fame relatively late to life and not until he was in his mid-thirties. He had spent the years before then teaching art and five years fronting the pub rock band Kilburn and the High Roads, before finally meeting success when he went solo and released in 1977 his debut album under his own name on the then fledgling Stiff Records, the classic ‘New Boots and Panties’.

The band the Blockheads, which Dury built around ‘New Boots and Panties’, consisted initially of Chaz Jankel (guitar, piano), Norman Watt-Roy (bass) and Charley Charles (drums) and combined together elements of jazz, funk, rock ‘n’ roll, disco and musical hall vaudeville. For touring purposes, it soon expanded to also include Mick Gallagher (keyboards), John Turnbull (guitar) and Davey Payne (saxophone).

Dury’s lyrics on ‘New Boots and Panties’ mixed together Cockney rhyming couplets, clever wordplay and sharp observation, introducing such characters as the bragging, bedpost-notching brickie, ‘Billericay Dickie’; the sympathetic but slow-witted ‘Clever Trever’, and ‘Plaistow Patricia’, a former whore who still many years from her last trick was still unable to shake off her roots or a lingering heroin addiction. Other songs included ‘My Old Man’, a tribute to Dury’s late bus driver/chauffeur father, and ‘Sweet Gene Vincent’ a homage to his musical hero, the also crippled American rock and roller who had died in 1971, aged just 36.

Dury met with instant success with ‘New Boots and Panties’, and followed this with stand-alone single ‘Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick' which went to number one in the early weeks of 1979.

He put out two more albums with the Blockheads on Stiff Records, 1979’s ‘Do It Yourself’ and 1980’s ‘Laughter’. After this, he disbanded the Blockheads, and released four albums without them –‘Lord Upminster’ (Polydor, 1981); ‘4,000 Weeks Holiday’ (Polydor, 1984), which takes its name from the lifespan an average person can expect to live; ‘Apples’ (WEA, 1989), which was the soundtrack to a musical he had written for the Royal Court Theatre in London, and the understated ‘The Bus Driver’s Prayer and Other Stories’ (Demon, 1992).

Shortly after being diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1996, Dury reformed the Blockheads permanently, recording one final album together, the much acclaimed ‘Mr Love Pants’ (East Central One, 1998) and touring with them regularly until his final gig at the Palladium in London six weeks before his death.

While all Dury’s records have been reissued many times before, a latest set of re-releases offers something new. ‘The Studio Album Collection’ combines together all of Dury’s post-Kilburn and the High Roads’ work in a nine CD set, (including a CD for singles and their B-sides), while ‘The Vinyl Collection’, which will come out in December, collects together all eight albums on vinyl.

“It is a great package,” enthuses Mick Gallagher at the start of an interview with Pennyblackmusic to promote them. Gallagher has been the main spokesperson since Dury’s death for the Blockheads, who continue to tour. “It is Dury’s complete catalogue together in a lovely package for those that don’t have it. I think that it is just wonderful.”

Pennyblackmusic spoke to him about Ian Dury and the Blockheads’ history.

PB: You didn’t appear on ‘New Boots and Panties’, but you became a Blockhead shortly afterwards when you were invited to join the Stiff’s Greatest Stiffs Tour to promote it. How aware were you of Ian’s work before then?

MG: Johnny Turnbull and myself were actually in a band just prior to Ian doing that album with Charley Charles and Norman Watt-Roy. We were called Loving Awareness and we were involved for a while with the pirate radio station, Radio Caroline. We put an album out on its owner Ronan O'Rahilly's record label (‘Loving Awareness’, More Love Records, 1976), and we did jingles and sessions for him.

Rhythm session players were always in demand, and Charley and Norman, as the bass player and drummer, got most of the sessions. After one session for Radio Caroline, I think an engineer, who had been working with us that night, suggested them to Ian and Chaz.

Charley and Norman went in and did the initial demos and subsequently the album, ‘New Boots and Panties’, and while they were doing it we, of course, heard what was going on and thought, “Wow, this is off another wall. This is really good.” So, when Ian released the album and wanted to go on the road and to augment the studio band, our names were put forward by Norman and Charley, and we got on board and Davey Payne also got on board at the same time.

PB: You were literally a band that came together on stage. You weren’t given a lot of time to rehearse beforehand, were you?

MG: That’s true, but Charley and Norman, myself and John had all been playing together already, so we were quite tight. There was some semblance of rapport between us anyway. We had been playing together for four or five years at that stage, and I had known Johnny Turnbull for even longer than that. We had been playing together since he was sixteen and I was twenty. We had an empathy if you like, and that came to the fore on the Stiff tour because Ian suddenly realised that he had a kicking band (Laughs).

PB: Ian has been described as “taking punk out of exclusively teenage values into a much wider sphere.” He was never really a punk as he was first of all too old and secondly what you were all doing musically extended far beyond that. How did he feel about punk? Was he happy to be seen as some sort of father figure there or did it annoy him?

MG: No, he embraced it because it he was a wordsmith more than anything else, and punk was a backbone for getting those words out. Music was the medium he used but the remit of his medium was pencil and paper, and punk gave him a platform to do that. We were quite long in the tooth, but punk gave us all a base to go out and play music which we loved playing. We were sort of punk punk (Laughs).

PB: You toured with the Clash and appeared on their albums ‘London Calling’ and ‘Sandinista!’ How did Ian and the rest of the band get on with people like John Lydon and Joe Strummer?

MG: There was both a standoffishness and a recognition of each other. They weren’t like mates, but they were supportive in ways that they could be without hanging on the coat tails of each other. There was both a mutual respect and a musical dislike (Laughs).

PB: You toured regularly across the UK and eventually in Japan and Australia, but you only toured once across America. Why was that?

MG: Ian wasn’t great at travelling. He had this disability that he tried to ignore most of the time, but long distance travelling wasn’t his thing. He wasn’t enthralled with America. The band went down great, but the Americans saw Ian as this very strange English geezer hobbling around the stage and shouting. They got the band but they didn’t get him, and I think that was one of the reasons why he was a bit disenchanted with it (Laughs).He used to say that it was working at right angles.

PB: You did that tour with Lou Reed?

MG: We did that tour with Lou Reed. Sometimes we blew him off stage. We were so enthusiastic, and he was this cooler-than-cool New York rock star with a similar attitude at the time to his music. We went on stage first and we went on to kill him (Laughs).

PB: Apparently Ronnie Wood and Rod Stewart turned up one night and tampered with Lou’s guitar strings.

MG: They came along to a gig in L.A. We had a chat backstage and said how moody Lou was. He was very moody on that tour, standoffish. Few words came out of him in our direction, and as they went off they passed his desk and detuned his guitar (Laughs). It completely ruined his set. It was like being hit with a van. Lou predictably went crazy.

There was another time in Philadelphia in which we had done our set, and the dressing room was right next to the stage, and the only way out was to go across the stage. So, we waited until Lou was just about ready to go on, and the audience was really wound up, and we said, “Right, we are leaving.” We had this big Philadelphia police woman with us who escorted us off the stage, carrying all our suitcases and waving at the audience. They were expecting Lou, who went up like a rocket (Laughs). There were incidents like that of one-upmanship and gamesmanship throughout the tour.

PB: Ian notoriously didn’t like his band mates to be too comfortable on tour and would often take steps to be confrontational and wind you and the others up. Do you think that he did that just so that when you went on stage with lots of anger and fury and played a really explosive show?

MG: In a simple word, yes. He was like the cog in the centre of the wheel and he would go to a lot effort to try and keep us apart as individuals, so that we communicated through him rather than with each other. He was a control freak, but it worked. We were prepared to go along with it because it was working, and in fact it wasn’t until Ian died that we really got to know each other. The four of us knew –Norman, John, Charley and I – had already known each other for a long time, but getting to know Davey Payne and Chaz Jankle took years.

PB: He did something similar with ‘Do It Yourself’ as well. He put several members of the band in different rooms, handed out lyrics and told them to come up with the music, didn’t he?

MG: That came from his days of being institutionalised himself because of his disability as a child. He was very much of the Protestant ethic of work whereas the rest of us were more Catholic in our approach to it and, when we working on ‘Do It Yourself’, we went down to this big house in Wolverton which he had hired for the occasion and it had lot of rooms, so I would be in a room with a piano, Johnny would be in another room with a guitar, Chaz would be in the front room , and Norman would be working on something with Charley, and he would visit the rooms and see how we were all getting on (Laughs). We all had different songs that we would be working on. It was like a little college. We all thought that it was hilarious.

PB: It took two years for ‘Do It Yourself’ to come out after ‘New Boots and Panties’. Bands were putting out albums at that stage often as little as six months apart. Why did it take you so long to put it together?

MG: Ian decided to do things at his own pace. After we had a number one hit with ‘Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick’, Ian decided to go on holiday for a year. We had no idea that he was planning that, and suddenly he said, “Right! I am going on holiday.” That is why I went off and toured with the Clash because Ian wasn’t working. He went on holiday and in fact took most of the band with him, who all had a busman’s holiday, and I decided to go off and tour wiith the Clash. We have never followed rules though. We have always done things our own way. We had to make some concessions towards Ian’s physicality.

PB: With regard to that, the Blockheads had a policy with the early records of not putting out singles on albums or even allowing singles to come off albums once they had been released. Why was that?

MG: To be cool (Laughs). That was down to Ian. It was just to be controversial. ‘Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll’ was on one of the first versions of ‘New Boots and Panties’, but it was taken off. Ian thought that if you didn’t put the single on the album people would buy the single and the album. I wasn’t a Stiff Records thing. It was Ian saying, “I don’t want any singles on the album.” With hindsight, I think he would he have probably sold more albums if he had had the singles on them.

PB: ‘Laughter’, despite its title, is not a happy album at all and a lot of its subject matter was pretty dark. Ian was by this stage drinking heavily and was addicted to painkillers as well. Was that just a reaction against fame? Once he had got this fame so late in life, did he find it very difficult to live up to it?

MG: He liked the fame, but it was the commitment that came with fame that he didn’t like. ‘Laughter’ was the third album of a record deal that he had signed with Stiff to get new teeth. Every album that he did was to get new teeth.

He had done ‘New Boots and Panties’. He had done ‘Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick’ and ‘Do It Yourself’, and ‘Laughter’ was the last album that he was committed to for Stiff. Chaz had gone off to be a film score writer in L.A. People were deserting the ship. I had gone off with the Clash, and he pulled everybody together so that we would do this last album.

The Blockheads in fact were doing our own stuff in a studio in Fulham, and he turned up after having been away on holiday again and said, “Oh, this is a nice situation,” and so he hijacked the studio and started paying us to do a new album which was ‘Laughter’. There were a lot of painkillers and alcohol involved and his lyrics were brutal, but they are true. As a poet and a writer and an artist, he had the right to do that. We didn’t want to just do ‘Top of the Pops’ and that was it. As musicians and artists, we wanted to do something that meant something to us, and ‘Laughter’ was a reflection of that and how Ian felt at the time.

PB: Chaz Jankel had been replaced by Wilko Johnson from Dr Feelgood. How did that change the dynamics of the group?

MG: It was difficult for Ian because Chaz was his main writing partner, and their break-up wasn’t particularly amicable. Chaz wanted to go off and do his thing and was quite justified in doing so, but Ian hadn’t really expected him to and was pretty upset about it.

I think Ian met Wilko at a gig. He had just left Dr Feelgood and was moping around and Ian said, “Why don’t you come and join the Blockheads? We’re making an album”, and so Wilko came along and was on ‘Laughter’.

PB: Did you find yourself having to write around Wilko a lot because he has such a unique and original guitar sound?

MG: It was a bit weird incorporating it with the Blockheads. It did give the band a rougher edge than before, but again we embraced it.

PB: After the Blockheads folded, you stayed with him and helped him write the songs for his musical, ‘Apples’.

MG: Ian had a residency with at the Royal Court Theatre in London. He used to do a bit of acting and met Max Stafford-Clark, who was the Artistic Director there at the time. He invited him to do a musical, and so we worked on ‘Apples’. He wrote the songs, and then he wrote the play around them which is the wrong way round (Laughs). He should have written the play and let the songs come from it. We enjoyed it, but it wasn’t well-received by the critics and closed after just a few weeks

After that we were given the opportunity through Max Stafford-Clark do some stuff with the Royal Shakespeare Company. We set a few period pieces to music. We used to go for walks in Richmond Park and plot up things like researching Morris dancing music in the sixteenth century. It was fun. Nobody took us up on any of that, but that material is in the vaults of the Royal Shakespeare Company now. We did try and record it, but it would have involved about twenty people and we were told that it was too expensive.

PB: You also worked with him on ‘The Bus Driver’s Prayer and Other Stories’ album.

MG: That was a very personalised little record. We got various friends in to do things like Mervyn Rhys-Jones, and Johnny Turnbull, Chaz and Davey Payne all also appear on it, but not always together. I enjoyed doing that album. There are some good songs on it like ‘The Jekyll and the Prawn’ and ‘The Bus Driver’s Prayer’. It is probably the least known of all Ian’s records, but it is one of my favourites.

PB: Many people see ‘Mr Love Pants’, the final Blockheads album, as the natural successor to ‘New Boots and Panties’, and Ian himself described everything else “as inferior and in between.” How do you feel about that?

MG: We all felt that too. We all felt good about ‘Mr Love Pants’. By that time Ian had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. When we had been in the studio beforehand, he was always very angsty and difficult. He always felt that he was under a lot of pressure when he was in the studio, and suddenly he had been diagnosed and we went in and did the album and he was really relaxed. It was the first album which we ever did together that he was really calm, and his performance and his delivery and they way the songs were written, everything about it was really done in a lovely place. There is a real rosy glow about that album.

PB: You toured extensively in the two years up until his death. What were those tours like in comparison to previous tours?

MG: Well, obviously, difficult, because the physicality of them got worse. Through his treatment he got five years extra to his life, but the quality of his life went down. He, however, wanted to keep working – and I can understand that. If you have got a sentence over you like that, those two hours on stage every night are the one time that you are not thinking about it.

That was really the reason why the band continued. It was pretty difficult standing on stage and watching him sit on a stool and sing ‘Wake Up and Make Love to Me’, but then at the same time that was the reason he was doing it. It was giving him an escape from it.

PB: Did he still used to wind you up before you went on stage or had that gone?

MG: The energy had gone, but the quips and the little looks were still there. The little cheeky look was still there.

PB: He played his last gig six weeks before his death at the London Palladium. Was there a feeling of finality about that occasion?

MG: I think there was. The reason that we did the Palladium was to make it a stand-out gig. We are of the generation when playing a gig at the London Palladium was seen as being the height of the entertainment world. There were lots of shows filmed here on the telly in the 1960s and 1970s with Bruce Forsyth and entertainers like that. We knew we had reached a certain pinnacle to do a gig there. It was lovely. Mo Mowlam and lots of people came down to see it. It was really warming.

PB: You were together with Ian off and on for twenty three years, and have continued to play together in the fourteen years since his death. Ian said about the Blockheads that “We’re proud of ourselves. We’re the best of what we did.” Is it simply because of that that you continue?

MG: Yes. We felt that we were in our own field. Nobody did the stuff that we

did, the quirky humour and the Englishness and the musical hall slant and the heavy funk. We wanted to continue because we enjoy playing together, and we are still going on. We released an album last year called ‘Same Voice Different Jockey’, which got a great reaction.

We are a little cottage industry these days. We were involved with a record label, and we ended up losing the rights to an album we had made when they decided not to release it. It was devastating at the time, but we just went out on the road and played live until the pain from that went away. Then last year we decided to do another album, and this time have released it ourselves through Kickstarter.

PB: Did you ever think after Ian’s death that you should stop?

MG: We did. We stopped for a year (Laughs), but Chaz used to have his own studio off Holloway Road in London, which was very convenient for people just to drop in, and so we used to pop in and see each other and have a jam and play around and it went from that to starting to do gigs again.

PB: Who does the singing now?

MG: Phil Jupitus, the comedian, who is a big Blockheads fan, used to guest with us sometimes, but we did most of it ourselves. Chaz in particular has a good voice, but the character was gone. We didn’t have that character of Ian, and so we asked Derek Hussey, who had been Ian’s minder and driver, to take over.

He didn’t have a job anymore, but he still would come along to gigs and so we would get him on to stage do ‘Clever Trever’ and ‘Billericay Dickie’, which were the character things, and he could do because he has a similar attitude to Ian. They drove around together for years and had the same sense of humour, and slowly he became more and more centre stage. He ended up writing all the lyrics to the last two albums, and very good they are too.

Who have thought it at our age? We have all got bus passes now (Laughs). We are past it, but are still going and enjoying every moment of it.

PB: Thank you.

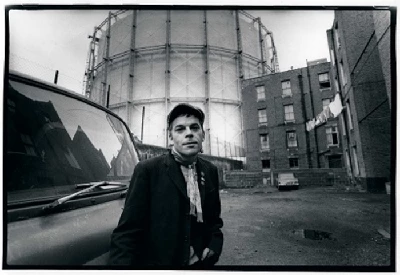

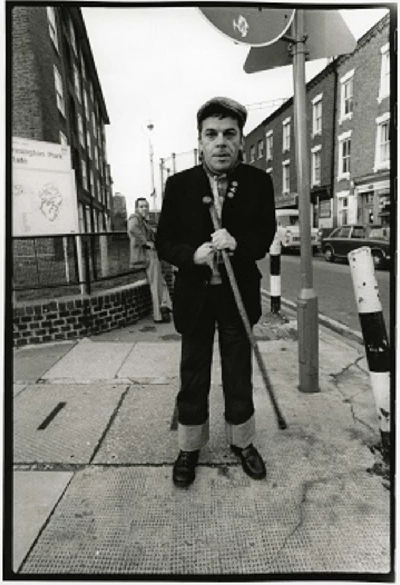

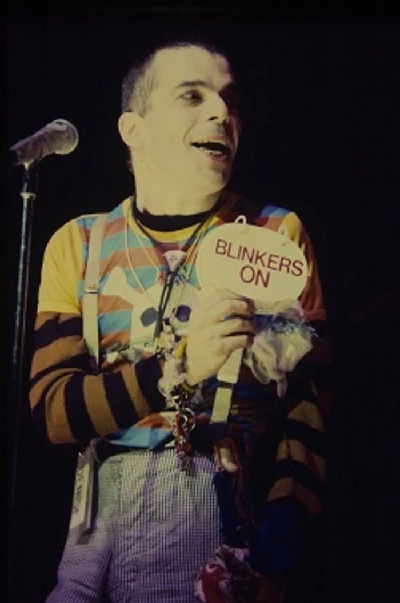

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

727 Posted By: Don Sawhill, Placerville, California on 25 Nov 2014 |

Great piece, Mick clearly was very fond of Ian !

|