Delines

-

Interview with Willy Vlautin

published: 7 /

5 /

2014

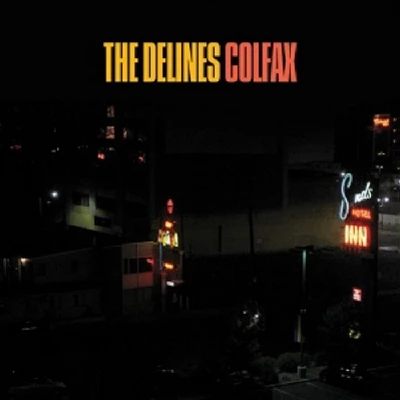

Richmond Fontaine frontman and singer-songwriter Willy Vlautin talks to John Clarkson about his new band the Delines, their debut album 'Colfax', and 'The Free', his recently published fourth novel

Article

“We drove into Denver and they parked their car across the street from a place called the Bluebird Theater on Colfax Avenue. I told them thanks and started walking down the street…It wasn’t a good part of town. There were liquor stores and bars and dirty magazine places. I saw a drunk black guy pushing an empty baby stroller and I saw a guy whose face was deformed and a woman who yelled at a man and said horrible things to him and chased him around a Walgreens car park.” (Willy Vlautin, ‘Lean on Pete’, Faber and Faber, 2010, Pages 241-242)

One of the longest streets in America, Colfax Avenue in Denver is renowned for its down-at-heel nightlife – its strip joints and sex shops, its rough bars and its prostitutes.

Singer-songwriter and acclaimed novelist Willy Vlautin set part of his 2010 third novel ‘Lean on Pete’ on Colfax Avenue. Its fifteen year old narrator Charley, a runaway, winds up there for a while, before fleeing after hitting with a tire iron a local criminal who has beaten him up and robbed him. Now the Richmond Fontaine front man has revisited it again with ‘Colfax’, the first album from his new band, the Delines.

“I played for twenty years on Colfax”, he tells Pennyblackmusic on the phone from his home in Portland, Oregon. “And we played every bar there. We played all the bad bars and then we would play a good place. Then people wouldn’t show up to the good place, and then we would go back to the bad place. It was just a constant up and down. You kind of equate how your band and life is doing by which club you are playing there. Our van broke down a couple of times on Colfax and we got snowed in on Colfax. It is not as bleak as it was, say, ten years ago, but it is a miles long avenue and it is littered with run down shops and things like any bad street in any town.”

“‘Colfax Avenue’, the song which gives the album its name, is about a woman going to look for her brother,” he adds. "He has just got back from Iraq, and he has had a really rough time there, and he is this aimless alcoholic and he disappears there. She goes looking for him at night. I thought that feel of that street fitted the whole feel of that record and in particular that song.”

‘Colfax’ is something of a departure for Vlautin, who has recorded ten albums now with Richmond Fontaine including the albums, ‘Winnemucca’ (2002), ‘The Fitzgerald’ (2005) and ‘We Used to Think the Freeway Sounded like a River’ (2009). While Vlautin has always been the lead singer in Richmond Fontaine, he has handed over vocal duties in the Delines to Amy Boone, whose sister Deborah Kelly, with whom Boone co-shares vocals in the Texan band the Damnations, provided guest vocals on two other Fontaine albums, ‘Post to Wire’ (2004) and their last record ‘The High Country’(2011).

‘Colfax’ has allowed Vlautin to write through the versatile Boone for the first time in his song writing career from a woman’s perspective. It songs, as are most of Richmond Fontaine’s songs, are character-driven. These include ‘The Oil Rigs At Night’ in which a young wife runs out on her passionless marriage while her husband is working offshore, and ‘I Won’t Slip Up’ in which an out-of-control teenage girl tries to seduce a neighbour into giving her a downtown so that she can go drinking. Elsewhere on ‘He Told Her the City was Killing Him’ a lonely woman falls in with a volatile drifter and tries to convince herself that staying with him is better than being alone, while on the final song ‘82nd Street’ its narrator manages to get away from the life that that was destroying her.

As well as Boone on vocals and piano and Vlautin who plays guitar, the Delines also consists of the Decemberists’ Jenny Conlee-Drizos on keyboards, Richmond Fontaine’s Sean Oldham on drums and percussion, and two other local Portland, Oregon musicians Freddy Trujillo on bass and Tucker Jackson on pedal steel. The music on ‘Colfax’ has a late night country soul vibe and is achingly sad, epitomised by the album’s one cover, ‘Sandman’s Coming’ which, written by Randy Newman, is an eerie lullaby in which Boone soothes her baby daughter to sleep by warning her that life doesn't usually work out and that she can always expect the worst out of it.

Vlautin has now written four novels. His first novel, 2006’s ‘The Motel Life’ - about two teenage brothers in Vlautin’s home town of Reno, Nevada who go on the run after become involved in a hit and run accident - has just been made into a film starring Emile Hirsch, Stephen Dorff and Kris Kristofferson. His second novel, 2008’s ‘Northline’, is about an under-confident and alcoholic waitress, Allison Johnson, who flees from Las Vegas and her detestable Neo Nazi boyfriend after becoming pregnant and tries to begin a new life in Reno in Nevada.

His latest book ‘The Free’, which came out in late January, tells of a young brain-damaged Iraq veteran Leroy, who waking up in a rare moment of clarity, attempts suicide by throwing himself down a set of stairs onto some spikes. As he lies afterwards in a coma in hospital, he enters a nightmare dream world in which he and his girlfriend Jeanette are chased across America by a supremacist organisation called The Free. The book also focuses on its two other central characters – Freddie, the night watchman at Leroy’s group home for disabled men, who working two jobs already and heavily in debt starts a cannabis farm to pay off his daughter’s hospital bills; and also Pauline, a nurse at the hospital, who, looking after her mentally ill but emotionally abusive father, has as a survival mechanism detached herself from the world.

In what is our fifth interview with him, Pennyblackmusic spoke to Willy Vlautin about both his new book and also ‘Colfax’.

PB: How were the Delines formed? There seems to have been conflicting stories - one that Amy Boone invited you to write the album around her after a drinking session, and the other that you decided to form the band around her after listening to her warm up by singing country records when she was on ‘The High Country’ tour?

WV: Well, both are true. I have been a fan of her and her sister Deborah Kelly’s band the Damnations since the 1990s. Deborah sang on Richmond Fontaine’s albums ‘Post to Wire’ and ‘The High Country’, and then, as Deborah was pregnant, Amy toured with us for ‘The High Country’ tour. When we were on tour, she did used to warm up by messing around with country/soul tunes, and her voice would just kill me. Then one night when we were on the road and we were drinking she said, “Hey, we don’t you write me a batch of songs?” I think she was messing around, but I took her seriously and went home and started writing songs for her.

PB: Was it difficult writing an album from a woman’s perspective? You have written from a woman’s perspective in your books ‘Northline’ and ‘The Free’, but had not written many songs from the point of view of a woman before. Was that hard?

WV: It was really freeing. I had always written songs before around my own voice in Richmond Fontaine, and what it can do and what it can’t do, and what I feel comfortable singing abou and have got the guts to sing about (Laughs). Amy doesn’t, however, suffer from the same limitations. I really took my handcuffs off myself with this album. I had always loved those country/soul epics, but I had never felt comfortable singing them myself.

It was really fun because I could write songs that edge towards the classics and which were bigger songs, whereas I never felt that I could do that with my own vocals. At another level it, however, made me really nervous because Amy is a close friend, and the last thing I wanted to do was let her down.

PB: How long did it take you to write ‘Colfax’?

WV: I don’t know how many songs I wrote exactly, but I wrote a lot more than the ones I used on the album. It was while I was working on ‘The Free‘, and it took over a year and a half. During that period I was constantly chipping away and working on songs for her. I didn’t show her any of them for a year. I am one of those guys that prefers to have the concepts and the ideas of what I am doing in place before I show it to anybody, just so that I can explain it.

Every time I wrote for her I pictured her going to work as a secretary in a big city and having a drink before work, meaning that at one level that she is kind of cracking up and falling apart, but at another level she is not really as she is still getting up in the morning and going to work. I was trying to tap into her resilience of character.

PB: ‘Colfax’ was co-produced by John Askew with Sean Oldham and yourself at his studio in Portland. John worked on both ‘Winnemucca’ and ‘The High Country’ with you. ‘Winnemucca’ in particular is a masterclass in restraint. ‘Colfax’ similarly has as simmering undercurrent of tension. Was that why you wanted to work with him again because you knew that he could get for you that sound?

WV: Yes, I knew that he was interested in making that kind of sound. We had as well such a good time working with him on ‘The High Country’. John always thinks of things in terms of movies. He is a very cinematic producer. He always thinks of things in an epic, soundscape way. He is really into the feel and the vibe of the song, and I really relate to him on that.

Both ‘Winnemucca’ and ‘Colfax’ are restrained. I think of ‘Colfax’ as being a record after you have gone out for a night and you don’t want to quite stop. You want to have a couple more drinks and you don’t want to rock out, but want to have a late night record that will make you stay up too late. ‘Colfax’ is that kind of record. ‘Winnemucca’ in contrast is the kind of record for when you wake up the next day and you want to get yourself going. If there is a Sunday morning hangover record, then ‘Winnemucca’ is that kind of record.

PB: ‘Colfax’ has a timeless feel. It could have been made at any point during the last fifty years. A lot of the stories on it are also timeless. The characters on it go through sort of dramas and tragedies that happen to people time and time again and have for generations. The stories about the young girl running wild on ‘I Won’t Slip Up’ and the woman preparing to leave her husband on ‘The Oil Rigs At Night’, for example, will all have taken place countless times. Was that why you wanted to record ‘Colfax’ in this style, as a reflection of that timelessness?

WV: Yes, I have always thought that Amy had a timeless kind of voice. We use a lot of Rhodes piano and pedal steel on this record, and I have always been in love with that combination of instruments. I have always thought that if you put them together right they marry together in a really beautiful way. I think that they give this record a lot of its late night feel.

I also wanted the lyrics to have the feel of or just to be a little grittier than you would find on, say, a Sammi Smith record or some of the quieter Bobbie Gentry tunes. I wanted the lyrics to be a little more intimate and to have a little more grit to them. I felt that was my job to push them a little bit more in their intensity than you would find on those older records.

PB: You have covered Randy Newman’s song ‘Sandman’s Coming’ on ‘Colfax’. It is a pretty bleak song. Why did you decide to put that on there?

WV: I am a huge Randy Newman fan, and Randy Newman was an inspiration to me for a lot of these songs on this record. Amy is a really good piano player, and it is just her on that song, playing that record live one night in the studio.

That song, however, sums up to the whole record. The idea is that there is no lucky break. The narrator of the song is saying. “Hey little girl, they are just lying to you if they say that it is not going to be awful. It is going to be hard.” All of the women on the record could be the small child who the narrator is singing to on this record. They could be that same little girl growing up. I like it because it is such a rough, unwelcoming lullaby, but it is really truthful. It is like the mother is saying on it, “Things are going to be rough for you. Things aren’t going to be easy. You are never going to get anything for free, and you are going to get your heart broken again and again.”

PB: You finish the record on ‘82nd Street’. It is not in any way a hopeful record, but it is perhaps the most hopeful song on the entire album as the main character has escaped from this life that would have eventually otherwise killed her.

WV: 82nd Street is really Portland, Oregon’s Colfax. It is about this woman who had led this really fast and kind of nasty, hard life, but now she is out of it. The idea of that song is that you wake up in the morning and you are not hungover, and you go about your day and you see all these people stumbling down the street and trying to get home. You feel like you have escaped it, that you made it through that maze and that you’re not like that or destroying yourself anymore. It is a very great feeling, and moves back to that theme of resilience once more. All the characters on this record are beat up and dented but still resilient. I think Amy carries that feeling really well.

PB: Was it important to you to finish on a note of hope as well?

WV: I didn’t feel that this record was as bleak and as rough as some of Fontaine’s records, although a lot of people have disagreed with me on that. That song just feels right at the end for me. It has this dreamy feel, and I wanted it to end on an easier, settled down note, like “Finally I have made it to a place where I can rest.”

PB: To move on to talk about ‘The Free’, the character of Freddie in ‘The Free’ has similarities to the character in your song ‘43’ on ‘We Used to Think the Freeway Sounded Like a River’ in that he becomes involved in running a cannabis farm to pay off a relative’s hospital bills. Was ‘43’ the starting point for Freddie’s character or did something else give you that idea?

WV: It was around the time that were starting to work on ‘We Used to Think the Freeway Sounded Like a River’ that I really started thinking about ‘The Free’. Most of the time my lyrics in my songs are sketches for a novel. I think that every novel I have written has started as a song.

The woman in ‘A Letter to the Patron Saint of Nurses’, which is also on ‘ We Used to Think the Freeway Sounded Like a River’, is also an early version of Pauline. The working title of the book right until the very end was ‘A Letter to the Patron Saint of Nurses’.

‘43’ is basically the same story, but in the song the guy is taking care of his mother, not his daughter. He is still in debt, however, and running a marijuana grow operation in his basement. It is a story that never quite left me. The main characters and the ideas of ‘The Free’ kept shaking me until I sat down and started getting it together.

PB: The three main characters of Leroy, Pauline and Freddie all briefly touch upon each other’s lives, but they live very separately from each other and they spend most of the novel apart from each other. Did ‘The Free’ start out as three separate books?

WV: No, I definitely wanted to mix these three characters together from the start - a nurse, a guy who is drowning in medical bills and works in a group home for disabled men, and this injured war veteran together. I wanted to write about the effects of war and about long term care giving in a group home, and the effects of that on Leroy’s mother Darla and his girlfriend Jeanette as well. I see the main theme of this novel as being about nursing, and all that it entails from the viewpoint of a nurse to care givers and to the wounded.

PB: It is also a novel about Iraq. Iraq is a forgotten war. There is little mention of it in the press now in either the United States or the United Kingdom. Was one of the other themes of this novel for you, to give its soldiers a voice?

WV: Yeah. The nearest military base from Portland, Oregon is maybe a hundred miles away, and so you don’t see a lot of returning soldiers around here. The papers very seldom talks about it, and it is never at the forefront on any radio or TV programes. It has been forgotten about. I was horrified and ashamed that so many of these guys were coming home with brain injuries

The problem of brain injuries is that you can’t control your emotions. Your dark times are extremely dark, and you often go down dark holes that you can’t quite get out of. Most of the soldiers in the United States are soldiers because they have nothing else going for them. There are mainly small town guys. I am not talking about officers. Where the army gets the most recruitment is through jingoism and poverty.

I didn’t feel I was the right guy to write about war. There are obviously great books coming out about the effects of war about Afghanistan and Iraq, and there have always been great novels by soldiers. What I thought I could offer and write about was the costs of care giving and nursing. Everybody alive knows of someone who has had to take care of someone with a long term injury, and where I wanted to focus my attention was on the aftermath.

The government hires the soldiers, gets them to join up and sends them overseas, and then they get hurt and the government stabilises them. The army sets them up as best as they can and then they move on, and it always lands on the family’s back. I am a big advocate for care giving, and my intention with Leroy was to discuss that aspect of it, and also to put the reader in the mind of a guy who sees great darkness on a daily basis.

PB: You’re a writer who both in your songwriting and novels has always focused on the real world, but much of ‘The Free’ is set in this alternative fantasy/dream world in which Leroy goes into after he has attempted suicide and is hospitalised. Was that the most difficult part for you to write?

WV: It was actually the easiest. It was the most liberating and it was fun. It was romantic. I liked the fine window between reality on the outside world around him and in his hospital room to what is going on his dream world, his escapism. That was really fun for me.

The hardest part of the book was writing about Freddie and Pauline because they get no breaks. I wanted to write about two people that have no escape, that are working class, and one of whom is working two jobs. That was really hard because every time I wanted them to have some fun I had to handcuff myself back to the mission of the novel and to keep them in the grind. They are in the grind though like most people are in the grind. That was the hardest part.

PB: Last few questions. ‘The film ‘The Motel Life’ has just been released. How much involvement did you have in its making? Were you on the set a lot?

WV: No, I had no real involvement. I showed the two guys, Alan and Gabriel Polsky, who directed and produced it around Reno. I told them what I thought and that was about it. Then when Kris Kristoffersen was filming his scenes they knew I was a big fan and so they invited me down.

I was on the set for a couple of days, but I didn’t feel very comfortable being there. There was one scene where Kris Kristoffersen was sitting in a restaurant that I had eaten at since I was a little kid. He was even sitting in the same booth that I always sat in, and I would have still changed some of his dialogue (Laughs). In my mind I was thinking, “I don’t think that he would have said it exactly like that,” and that was when I knew I had to get the hell out of there.

It wasn’t my project. It was the filmmakers’ project rather than mine. Overall I am really happy with it though. Those guys worked really hard and made a really good film. It was made with a lot of love, and I really admire it what they did with it.

PB: What is the situation with Richmond Fontaine now? Your bass player Dave Harding is now based in Denmark. There are less opportunities as a result for Richmond Fontaine to meet up and work together. Was Dave’s absence another factor in you deciding to form the Delines?

WV: Yes, definitely. Dave is married to a Danish woman, and they moved to Denmark. I was having a really hard time writing ‘The Free’, and I needed at least a year off to finish that book. The band also needed a break and Dave was leaving. We have always been a group that has taken breaks from each other, and are the kind of band that it would be the death sentence of to push it too hard. I think that one of the gifts that we have is that we know when to push and when also to ease off.

One year turned into a year and a half or nearly two years, and, while we had hung out together separately, I don’t think we had all even been in the same room together. Then we decided to start playing again together because we had all missed it so much. We have just started rehearsing songs and preparing for another record right now and Dave is going to play on a couple of tunes, but the majority of them will feature Freddy Trujillo, who plays bass in the Delines.

PB: So, you have got two bassists in Richmond Fontaine now?

WV: Yeah, exactly (Laughs). Dave really wanted a change. We all miss him, of course, and we were sad to see him go, but a guy’s family always comes first. Married life suits him well and I know that he loves being a father. I am really happy for him.

PB: The Delines has been described as a side project. Do you see it as that or do you see it as another band?

WV: I have never seen it as a side project. Hopefully I will always get to play with the guys from Richmond Fontaine. I love them and we have been together a lot of years. The camaraderie of Fontaine is one of the favourite things that I have. The Delines is, however, a band in the same way as Fontaine as a band.

PB: You’re going out on tour and coming over to Britain in June. Are those going to be the Delines’ first dates?

WV: Yes, we are going to do some warm-up shows around Portland. The first real touring we will be doing will be in the UK. We will start in Ireland, and then we are going to come back and tour the States.

PB: Finally are you working on a fifth novel now?

WV: Yeah, I have been touring ‘The Free’ in the United States since January and also been working on Richmond Fontaine songs, but I am nearly a draft done with my new book.

WV: It is a kind of gift to myself. It is set in modern times and is about two cowboys that lose their jobs at the same time, and they drift down through Nevada and Arizona. It is a lot easier on my head than ‘The Free’. ‘The Free’ just about broke me, and I told myself that if I ever finished ‘The Free’ and could lay it to rest that I would give myself a gift of being around these two cowboys, and so that is what I am doing (Laughs).

PB: Thank you.

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-