published: 26 /

11 /

2011

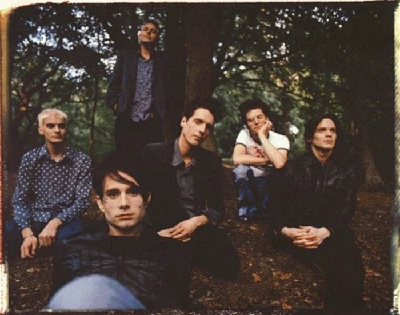

In the first part of a two part interview, Bristol-band singer-songwriter Patrick Duff talks about to Denzil Watson about his tormented, but seminal 1990's alternative rock act, Strangelove

Article

Musicians often tend to be tortured types. Many struggle to survive the excesses and the highs and lows that the rock’n’roll lifestyle brings. Modern music history is littered with the many casualties that have fallen by the wayside; Kurt Cobain, Ian Curtis, Billy Mackenzie, Richey Edwards. The list goes on. Perhaps it goes with the territory.

Patrick Duff, ex-Strangelove front-man and now established singer-song writer in his own right has been through the rock’n’roll machine and has come out the other side with a story to tell. And boy, what a story it is. From street busker in his native Bristol through to his recently self-released second solo album “The Mad Straight Road”, Patrick has quite literally been there, done that and got the T-shirt.

The interview I did with Patrick is probably the most honest and genuinely fascinating one I have ever done. Too compelling to leave anything out, I’ve had to split the interview over two parts. This, the first part, deals with Patrick’s days in Strangelove and his brief flirtation with Moon, his post-Strangelove project. Part two will look at how his solo career has subsequently unfolded. And, as you will see, it has indeed been, quite literally, a mad straight road.

PB: Patrick, can we start by talking about your Strangelove days? Do you look back at your seven or so years in Strangelove with affection?

PD: I’m really proud of it. I really think some of the music is great. It’s really stood the test of time.

PB: Listening back to your debut singles, ‘Hysteria Unknown’ and ‘Visionary’, they still sound extremely contemporary.

PD: Yeah, they do. It wasn’t always an easy time but I think we were always destined to break up. I can see that now but I don’t think any of us saw it at the time. I think that’s what made it good. It wasn’t going to last for ever. And we weren’t going to fulfil the sort of potential that we wanted to fulfil, to a certain extent. And in some way we always knew that so it gave us immediacy and a very specific energy.

PB: Your first album, ‘Time for the Rest of Your Lives’ was a really intense record wasn’t it?

PD: That’s probably me. It was my kind of influence on the record. I was writing very simply from the heart, about what was going on for me. I wasn’t schooled or I hadn’t done any study of literacy or poetry or writing lyrics. I just did it completely intuitively. The only words I could get out were the ones that were strong enough to get through. I was writing very directly without trying to hide between any metaphors. I was really going through something intense in my life at that point. It wasn’t made up. It was what was really happening to me. I think that’s what gives it its intensity.

PB: When you write in that way you tend to lay yourself bare, don’t you?

PD: Yeah, you do, but I didn’t ever find that difficult. I found it difficult when my authenticity was questioned in the press. But I never found it difficult to be honest about what was going on for me and that was a relief. At that time it was a very different climate than it is now. People weren’t so open about what they felt and there wasn’t really a currency of openness between people. Maybe it was because I was younger. But that’s how it felt.

PB: Was it a sort of therapy to get these things out via your lyrics?

PD: No, I don’t think it was really. It just seemed like the only thing to do. I wasn’t pushed but when we all got together we were all really creative people and the job fell to me to write the lyrics. I’d never really thought of doing that before to be honest. And so when it came down to it I just wrote about what was going on. That’s all I could do. There wasn’t too much consciousness behind it really.

PB: You had some high profile celebrity fans didn’t you? Radiohead’s Ed O'Brien, once said "We toured with them and changed quite a bit after. They were inspirational”.

PD: That has a lot of weight to it now. It helped us a lot that he said that because he said that at a time when Radiohead were becoming very famous. So that quote helped us and we got on with them very well. We were good friends with them at the time. They saw that we were breaking out. It was really cool to hear it.

PB: Another celebrity fan, the Manic Street Preachers' Richey James Edwards invited you to support them at the London Astoria on the penultimate gig before his disappearance in 1995 didn’t he? Any memories of that?

PD: I just remember how intense I felt their fans were. I didn’t know much about them at the time, although I really respect them and I really respected Richie. I think he was amazing. But I just remember this row of people with a massive amount of intensity at the front of the stage. I remember thinking, “Wow, this is very different to anything I’ve come across before.” We’ve supported all sorts of bands and there was something different about their type of fans. It’s something I can’t really put into words.

PB: Around that time you also supported Suede on their ‘Dog, Man, Star’ tour didn’t you? Was it frustrating that they enjoyed universal success while Strangelove remained more of a cult band?

PD: No it wasn’t frustrating. Maybe at the time it was but that’s now gone. I’ve very happy to be doing what I’m doing. To be honest I don’t really want to be saying what I was saying then now. I’ve changed a lot as a person and this isn’t any criticism of Suede, I supported them and I understand how exciting their gigs were. They are like a sort of umbrella for a certain type of person who feels like they are an outsider and when they come together at the Suede gigs and form some type of community that’s really important to those people. And so it isn’t just about the music, it’s about how they provide this focal point for these people to come together. And I can understand why they want to keep doing that because it’s exciting.

My past has been different though. When things don’t work out you’re forced to take that and look at it and you have to change. When things are going well you don’t have to change. It’s like in evolution; if something works it keeps on going. But Strangelove was doomed from the start. Basically it was a ship that set out from port and it had loads of holes in it and it was loaded with drugs and alcohol and other flammable material and it was never going to get to the port of success or longevity.

But I kind of think that makes it better in a way. I kind of like that now. I like the fact that it was flawed and it gives the music an intensity that can only be of that time. I can’t imagine what it would have been like if we had of had success. I would have still been playing those songs, but I can’t imagine it would be half as satisfying as writing stuff about where I am today. If you understand what I mean. I’ve had to let that person go. I’ve had to let that pop star person go and become the soil that I grew out of.

PB: You mentioned earlier that Strangelove were flawed. I certainly don’t think you could have said that about your second album ‘Love and Other Demons’ as there wasn’t a bad track on the album.

PD: No, I don’t think the music was flawed. When you’re in a band and you’re young you are influenced by all the rockumentaries you’ve seen. To a certain extent, because were from the west and that’s our sort of cultural history, it isn’t long but that’s what all bands are at the back of their minds thinking about. So in that sense we were flawed to become the next Rolling Stones.

I don’t think the music was flawed in that it wasn’t good enough, I think the fact that I was in a lot of trouble then as a person and I lived in a totally extreme way there was no way it could keep going. There is no way that I could have survived as that person I was in Strangelove, so in that sense there was no way it was ever going to last. But I think that the music that came out of that is fantastic for that very reason. It makes it better that you were flawed.

PBM: Out of the three Strangelove albums, which one is your favourite?

PD: I haven’t listened to the first one since we did it. I haven’t really really listened to the last one, ‘Strangelove’. I have listened to ‘Love and Other Demons’ and at the time I didn’t really know what I saw doing. I was out of my head. And if I wasn’t out of my head I was in a state of massive paranoia. So it’s really hard to be objective about the album. I listened to it in about 2003 and I realised that it was really beautiful and amazing album and it made me cry when I listened to it as I didn’t realise at the time. I had no idea that I had been involved in something that was that beautiful. So that was a real moment in my life and I realised, “Wow, that was great”. And no regrets that it didn’t go to number one. If Strangelove had hit the top of the charts I would be dead. I wouldn’t be here.

PB: That’s a pretty extreme thing to say.

PD: It’s just the truth. There would have been nothing stopping me.

PB: Well, you’ve kind of answered my next question. I was going to ask why, with success beckoning in April 1998, the band split?

PD: Well, I think by that stage things had changed. I think in a way we were the real thing and there were real lives in that band. Like the bass player Joe [Allen] who had really got into drum and bass stuff. At that point he was into Roni Size and all that. Alex [Lee] was writing a lot of his own stuff. I was writing a lot of stuff too. There was just not enough room in the band. Julian [Pransky Poole] was writing his own music. Everyone was wanting to put stuff into the band and there wasn’t enough room for it. That was when my song writing, because I’d stop taking drugs and drinking alcohol, was starting to become not just something I did intuitively. I started to really seriously think about it. And there was just too much.

I’d say that was what it was. And also because of that, coupled with the fact that when the last album came out it got to number 40 or something, but it was supposed to be going into the Top20. If you’re on a label like Parlophone and the other acts on the label are Radiohead and Blur and they are releasing albums and there’s a massive buzz about those bands and they’re doing amazingly well and you go into the office and you see and feel the vibe around those bands, it’s a small world and you think, “I want a bit of that for us”. So when our album didn’t go to where it was projected to go to, there was a really tough feeling for the band to absorb, and with all the creative frustrations which I just described going on we just didn’t have enough of what it took to absorb all that and stay together

PB: I saw you play in February 1998, shortly before the split, at Leeds Duchess of York and it has to be one of the most intense gigs I’ve ever been to.

PD: Yeah, it was an incredibly intense time. It was right at the end of the band.

PB: OK, a couple more questions about Strangelove. The band's B-sides compilation album, ‘One Up’, that appeared retrospectively in 2008 on EMI showed what a great B-sides band you were didn’t it?

PD: Yeah, I can’t remember. I’ve not listened to that compilation all the way through, although I’ve just clicked on the odd thing and had a listen. I think I clicked on the ones I remember being quire good. I think there were some good, quite creative and unusual things that came out.

PB: Given that every other band from the 80s and 90s has reformed, do you think Strangelove will ever reform?

PD: I don’t think I can see that at the moment but you never quite know what’s going to happen. I have played Strangelove songs since, including the last London gig I did and I did feel connected to it. But I don’t know if I’d want to be behind that amount of noise. I don’t know where it’s really where I’m at. What do you feel like when you see middle-age blokes get up and play the music they were playing when they were 20?

PB: I think it depends upon the circumstances and how you do it. I do remember reading somewhere that Feargal Sharkey wouldn’t join The Undertones reunion because it didn’t seem right singing ‘Teenage Kicks’ when he was in his 30s.

PD: The songs of Strangelove are full of angst. If you’re not feeling angst any more and the songs are really about that then they change into something else. I can imagine playing some of the slower stuff, but I can’t imagine doing the really full-on stuff. And it would be a bit weird not to do that stuff.

That came from a specific place and time and I was absolutely desperate when I wrote songs like ‘Time for the Rest of Your Life’. I was crying out for something and it was the only way I knew at that point. I didn’t even know what I really meant when wrote that song. It was really about that point of my life, about screaming out to a God that I didn’t even believe in because I was so desperate and needed help but I didn’t know where to turn to so I turned to something I didn’t even believe in. When I performed that song on stage that was what was going on at that stage. How could I do that now when it’s not that way any more? I could get in touch with that anger that was in me then as it’s probably inside somewhere, but it wouldn’t be the same thing.

PB: Okay, let’s move to your post-Strangelove outfit Moon. It didn’t last very long. What happened?

PD: The creative driving force behind that band was me, I think. But the real driving force was the drummer Don Jenkins. He came to me and said, “I want to start a band and I want to do it with you.” He’d been in bands before and been on the verge of getting signed for a long time and he wanted to get us a record deal. That’s what was driving him. And he wanted to make great music. So we decided to make a new wave band. I wanted to do something rawer than Strangelove and a little less sophisticated musically. Music that was more stripped down.

He [Dom] was saying, “We’re to do this gig and do that gig” because my mind didn’t work in that way, so I needed him and he needed me. He was able to muster up all the contacts I had. He had that kind of brain and he knew how things worked in the business.

So we did this gig in London and all the music press came. It was all set up for us to get this really good review and it didn’t happen. What happened was I got really personally attacked in the press. And that killed the band. We’d only been together for nine months. And Don understood that the fact that we’d been slagged off mattered a lot. It was a massive boot in the face because we’d worked really hard but we’d not been together for long enough to sustain that sort of blow.

PB: That’s a real shame because you had a really good set of songs when I saw you at the Garage in London. I remember a really beautiful song at the end of the set where you sat on the edge of the stage to sing it.

PD: Ah, yes, that was ‘Destination Moon’.

PB: What happened to all those Moon songs? Did you record any of the songs beyond the two tracks you did for the single?

PD: No. We might have done some demos but I don’t know what happened to them. The band was about trying to get back to where I was. I got used to that lifestyle. Being in a band, touring around with a record company supporting you. Having your wages come through every month. Your manager sorting everything out for you. I got very used to that. It was the only way I knew how to live.

When Strangelove ended it was like, "Shit!”. I was signing on and at one point I had someone saying to me, “What are you going to do now Mr Duff? You’ve been trying to get a job in music for six months now and nothing’s happened”. I remember sitting down in a Job Vacancies place and thinking, “Fucking hell man. This is heavy. I don’t want to get a fucking job. I want to do music. That’s what I do.” So it was really scary.

So having Don who was saying, “I’m going to get us a deal and get you sorted out again”, I just went with what he was saying. But for that to happen lots of pieces of the jigsaw had to be put into place, one of which was support from the press and another support from a record company. And neither of those things came along. So Moon ended and all the songs that I’d written in that period just hit the dust, basically. It’s quite sad really.

I didn’t have the foresight to say, “We need to get into the studio and make recordings of them. We need to document what we’ve done. Let’s go and do it. And stick it out ourselves”. None of that thinking existed then. Sticking an album out then that wasn’t on a proper record label was like a failure. Thinking was so different then. It’s hard to imagine it now. If it was now I would have just recorded those songs and make sure they were available.

And there we shall leave it for now. Part two which will be published next month will pick up on what Patrick did post-Moon as he started out on his solo career and bring us right up-to-date of his musical journey.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/PatrickDuffAr

https://twitter.com/patrick_duff

Picture Gallery:-