published: 21 /

2 /

2011

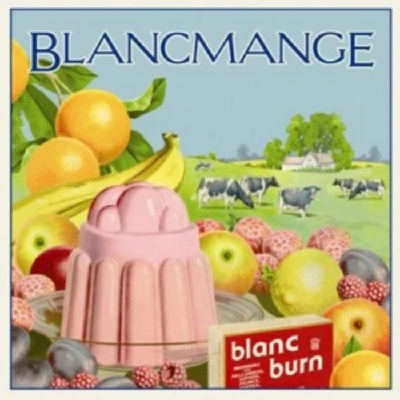

John Clarkson speaks to Neil Arthur from 80's electronica act Blancmange about their reformation after a break of 23 years and just released fourth album, 'Blanc Burn'

Article

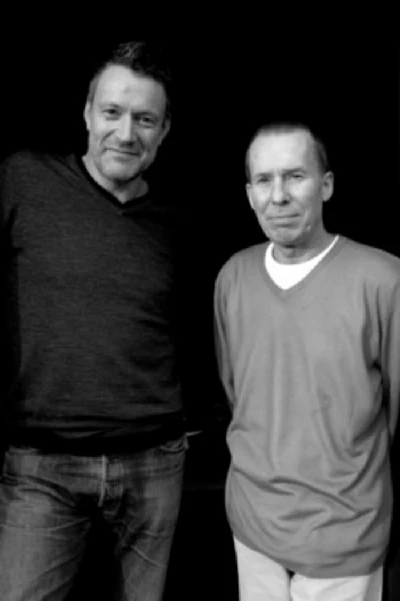

The last few years have seen the return of several of the key electronic acts of the early 1980s. Most of its major players seem to have made a comeback now. The reformation of the synth pop duo Blancmange after an absence of 23 years has, however, come as a particular surprise to many fans of electronica as both its protagonists, Neil Arthur (vocals, guitar and electronics) and Stephen Luscombe (synthesisers, keyboards), have since both gone on individually to have successful careers as composers of soundtracks for film and television.

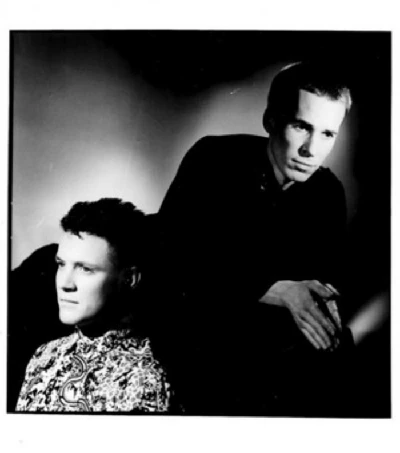

Blancmange formed in 1979, shortly after Arthur, who was brought up in the Lancashire town of Darwen, moved to North London to study at the Harrow School of Art and met Luscombe, who had been raised locally in the suburb of Hillingdon and was working as a printer.

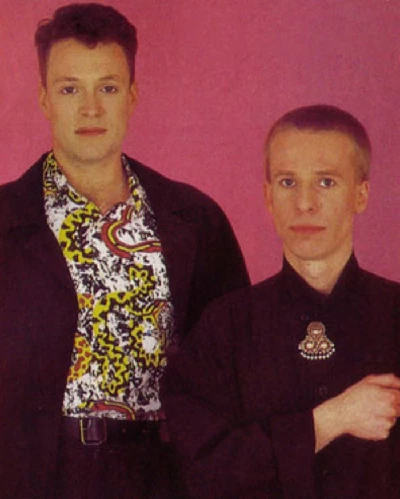

The duo released their first single, ‘Irene and Mavis', in a limited edition of 1000 copies on their own label, Blaah Records, in 1980, before signing to London Records in 1982. Over the next five years and before their break-up in 1987, they had a string of seven Top 40 hits including ‘Living on the Ceiling’, ‘Waves’ and ‘Blind Vision’, and also released three albums, ‘Happy Families’ (1982), ‘Mange Tout’ (1984) and ‘Believe You Me’ (1985).

Blancmange’s reformation has seen them release a fourth album, ‘Blanc Burn’, on Proper Records and also play their first British tour in quarter of a century.

While they masked it well with quirky videos and crisp, upbeat melodies, Blancmange were often bleak and lyrically intense. ‘God’s Kitchen’, their first single, revealed Arthur’s doubts in the existence of God. ‘Waves’ was about the after shocks of depression that come when a relationship ends, and their last big hit and masterly cover of Abba’s ‘The Day Before You Came’ was more about the monotony of day-to-day living than the flowering of a new romance.

Recorded almost entirely in Arthur’s home studio, and without the arsenal of guest musicians that were a recurring feature of their three other albums, ‘Blanc Burn’ is the most lo-fi of all Blancmange’s records since ‘Irene and Mavis'. The only other musician other than Arthur and Luscombe to play on it is Pandit Dinesh, an Indian percussionist and tabla player, who appears on six tracks and has been a presence on all of Blancmange’s albums to date.

The soaring melodies of their previous records are still there, but one has to search deeper to find them. Less instantly catchy and infectious than a lot of their back catalogue, and more subtle and slow burning than their other work, ‘Blanc Burn’ nevertheless grows with each new listening and ultimately is highly captivating.

The lyrics are also once again dark. Opening track, ‘By the Bus Stop@Woolies’, a spoken word song in which Arthur speaks his lyrics in a pantomime Lancashire accent through a voice distorter, finds him spikily remembering his early awkward forays into the world of teenage dating in Darwen. ‘The Western’, which thrusts Dinesh’s rattling percussion to the fore, is about illness, and closer, ‘Starfucker’, a mocking attack on the emptiness of celebrity culture.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Neil Arthur a few days before the start of Blancmange’s British tour about ‘Blanc Burn’.

PB: The first question is the obvious one. You have taken many of your fans by surprise and come back after an absence of twenty three years. Why have you decided to come back now and after so long?

NA: There was no formula or master plan. We had never really talked about doing it before and then a couple of years ago we were in the room at the same time, and asked the question of each other and both said yes. We agreed to see what happened. We said that we would write a few songs together, rather than talked initially about doing an album. We gathered momentum really last year and finished ‘Blanc Burn’ in the autumn.

PB: A lot of your contemporaries from the early 1980s have also reformed over the last few years such as OMD, Soft Cell, Yazoo and Heaven 17. They have all come back again after long absences. There seems to be something in the wind at the moment.

NA: There does seem to be, doesn’t there? From our point of view-and I’ll speak for Stephen. I am sure that he won’t mind me saying this-we didn’t walk away from music when we stopped doing Blancmange. We just found another way of doing it and really enjoyed doing it, and still do with the soundtrack work we do for film and TV.

I have always carried on writing songs and when this opportunity for me and Stephen to get together arose the nice thing about it was that - unlike the days of before when what we did was get a few demos together and then eventually ended up with a record deal - we allowed ourselves lots of development time.

I have my own home set up, a small thing for doing the film stuff on, and we did everything in my space and mixed it in a couple of mates’ studios to take it out of the environment that we had recorded it in. Then we presented the finished article to the record company. You wouldn’t have been able to do that twenty five years ago. That is one of the reasons actually why we did get back together, just that we have been able to do it our way. We have written, played and also produced it.

PB: The only other musician who appears on the album other than Stephen and yourself is Pandit Dinesh. He also contributed to all three of Blancmange’s albums. Could you conceive of making a Blancmange album without him?

NA:(Laughs) There are songs that he hasn’t played on. He didn’t play on ‘God’s Kitchen’ or our second single ‘Feel Me’ or ‘Waves’ or things like that, but he has been a mate ever since we recorded the first album. We first met him when we did a session for ‘Living on the Ceiling’. We did an original version which was purely electronic and then decided to add some percussion and also Deepak Khazanchi on sitar, and that was when we met him up with him.

We have recorded with and without Dinesh, but I always love working with him. In fact I am off to do something with him tomorrow and Stephen does all his film music with him. They always work together and had their own band together, the West India Company, for a while in the late 80s. Dinesh and I are also involved in a side project called AWP1 which we do from time to time which is an acoustic thing and breaks away from the electronics which I am normally surrounded by.

PB: The three previous Blancmange albums featired a lot of special guests. As well as Deepak and Dinesh, you had people like Malcolm Ross from Josef K and Aztec Camera, Hugh Masekela and Blair Cunningham from Haircut 100 and the Pretenders all making guest contributions. This album was recorded by just the two of you and at points the three of you. Was that a conscious decision to strip things back to basics?

NA: We decided very early that it was going to be me and Stephen and that Dinesh was going to come in and guest on several tracks. Part of that decision was made from a purely economic point of view. When we started working on the songs, Stephen and I, however, realised that we didn’t need anyone else. I am not sure if we made a conscious decision as such to go back to basics, but looking back on it now I can see that it was the very first time that we had done that since the very beginning.

PB: Maybe because it is more lo-fi than your other records, but much of 'Blanc Burn' seems to have a really sinister sound in comparison to the previous albums. You were always fairly melancholic as a group, but this album seems darker both musically and also lyrically than your other albums. Was that intentional?

NA: Not really. It just came out that way. There is a song called ‘Murder’, which started the second side of the vinyl version of ‘Mange Tout’ and I thought that was at the time it is quite dark. ‘God’s Kitchen’, our first single, was also fairly bleak as was ‘Feel Me’.

A lot of people have said that though. There was no intention to make it any darker than we had done in the past. I write the lyrics though (Laughs) and I guess that a lot of it is just down to me. I am 52 now. I am very excited about the future and I really like looking forward rather than back, but (Laughs) there comes a point as well when you think you should know all the answers to things and you realise that you don’t. Every day I learn something, but at the same time I seem to know less. I am intrigued by that. I consider myself to be open enough to want to know everything, but the one thing I am certain of is that I am less certain. I think that thought is reflected on a lot of the songs on the album.

I just write about what was there. I have written some stuff on there which is observations. It is not social commentary, but observations. If people want it to be social commentary that is fine by me, but it is just observations of what I see and feel and what other people have told me.

PB: ‘By the Bus Stop@Woolies’ is a real homage to a bygone age, not just to when Woolworth’s still existed, but before there were mobile phones and texting and when setting up a date with a girl was a major strategic operation.

NA: The story there was based on my own experiences of growing up in Lancashire and the really low expectations that you had of your relationship. At the same time, however, it meant everything to you. You didn’t have this kind of big world view on things. It was your world and a walk with a girl to to the kiosk and up to Lions' Den and round the bandstand and back over the tops, as I write about it in the song, was as often as big as it got.

The reference in the title was to how everyone going on these dates would meet at the bus stop outside Woolies. The bus stop is still there, although Woolies isn’t. I decided not to sing it and to do it in a Lancastrian accent. I put it on a bit more than it is, but it felt right for the song.

PB: ‘The Western’ seems to deal with illness and fear of illness. Was that what that song was about?

NA: There was this song from the 1980s by the Sound called ‘I Can’t Escape Myself’, in which the singer (Adrian Borland-Ed) was singing about how the person that he feared the most was himself and the idea of that has always me stuck with me. We do have these battles with ourselves. It was about fighting illness, but rather than it being a physical battle, I would say that it was more of a mental thing.

PB: ‘Starfucker’ shows an anger and a disgust with the national obsession with celebrity. Is this something which really annoys you?

NA: I live with it, but there is a sort of venom there I suppose. It was just about people can get obsessed with what is happening or going wrong with this celebrity or that one, but often lose sight of the fact that those people who they should be caring or worrying about, their friends and relatives, often have far bigger problems and difficulties.

PB: You are about to do a British tour. What can fans expect from you for that? Is it just going to be a mix of the old stuff and the new stuff?

NA: I think if we went out and didn’t play the old stuff there would be something wrong. We have got to go out and respect that there will be people coming along expecting to hear that. We will be playing the old material and also a fair smidgen of the new stuff. Maybe I’ll tell people about the material, “There is a new song coming on. If you would like to go and get a drink, off you go now (Laughs).”

PB: What are your plans after that?

NA: Remixes. We’re putting together a bunch of remixes and then we’ll do more dates for the summer. We are also hoping to tour Europe.

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/BlancmangeMus

http://www.blancmange.co.uk/

https://twitter.com/_blancmange_

Have a Listen:-

Picture Gallery:-