published: 9 /

2 /

2018

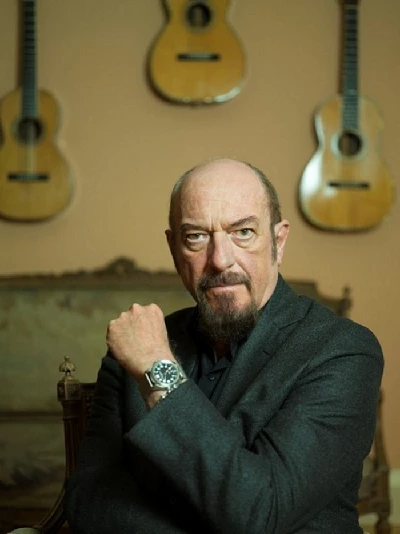

Lisa Torem speaks to Jethro Tull frontman and solo artist Ian Anderson about Jethro Tull's forthcoming 50th Anniversary upcoming UK tour, his favourite autograph and the curse of collaboration.

Article

Ian Anderson is best known as the front man, flautist and all-around multi-instrumentalist for British prog rock group Jethro Tull, which was formed in 1967. The Scottish-born showman is a highly prolific songwriter. The band’s discography includes ‘This Was’ (1968), ‘Stand Up’ (1969), ‘Aqualung’ (1971), ‘Thick as a Brick’ (1972), ‘A Passion Play’ (1973), ‘Songs from the Wood’ (1977) and ‘Heavy Horses’ (1978). Jethro Tull underwent multiple line-up changes over the years and shifted its focus between blues, folk, metal and prog rock.

Ian’s solo recording career began with ‘Walk into Light’ (1983), followed by ‘Divinities: Twelve Dances with God’ (1995), ‘The Secret Language of Birds’ (2000), ‘Rupi’s Dance (2003) and the sequel to 1972’s ‘Thick as a Brick’, entitled ‘Thick as a Brick 2’ in 2012, but his most successful solo album, ‘Homo Erraticus’ (2014), boasts a hybrid of rock, folk and metal.

His touring band members consist of guitarist Florian Opahle, drummer Scott Hammond, bassist David Goodier and pianist/organist/arranger John O’Hara, all of whom Ian has worked with since 2012.

Besides being an extremely gifted and versatile composer and player, Ian is knowledgeable about many other subjects. He remains heavily involved in addressing the plight of endangered species, loves Indian food, is a voracious reader and has appeared on popular American talk shows, where, along with other guests, he freely expressed his views on ‘Politically Incorrect’, hosted by Bill Maher.

Although I had interviewed Ian about world politics and Bengal cats in previous conversations, I was most keen this time around to help him spread the word about his upcoming 8-city UK tour, which will take place in April, 2018 and which salutes the 50-year anniversary of the making of Jethro Tull’s bluesy debut.

We also talked about Ian’s comfort with string quartets, his most cherished autograph and why collaboration is all-too-often a miserable word.

PB: It’s good to speak with you, Ian. How much input did your fellow musicians have over the selection of material you will be performing on your April 2018 UK tour?

IA: None whatsoever. The reason for that is quite simple, really. None of them were in the band when we first began. There were 33 different members of Jethro Tull, so most of the time, most of the members of the band have been inheriting the music that was recorded by their predecessors and so that is still the case today. And since I’m still wanting to focus on the first ten years of Jethro Tull’s music-making, since that’s the period of time in which most fans got to know about Jethro Tull, the guys in the band are not really involved in any decision-making on that score.

What we do, of course, is we talk it through. We try different songs, we rehearse them in sound check to see if we’re going to sound okay and I make a decision based on what we were playing last time we were on tour in that country and, of course, what we will do next year will be a little different. And it being a production show, we have to prepare the video and the virtual guest appearances--on the big screen behind me--and all sorts of things. It’s an elaborate job to put it all together and it’s best that I steer the ship and let the others man the mast.

The idea of taking people on tour, just to be able to announce a song, just to appear in context would be unbelievably expensive and it would also be insulting, just to say, “I want you along just to play this song and then bugger off.” That would be infuriating and frustrating and wouldn’t be a big bang for the considerable number of bucks, to get people from all over the world, put them in a hotel room, deal with all the IRS tax issues and all the government costs.

So out of the 33 members of Jethro Tull, you’ll only be seeing five of them, including me, and, as I said, none of them were the guys playing the original music. A couple of them weren’t even born then.

PB: Regarding ‘Jethro Tull – The String Quartets’, featuring arranger/keyboardist John O’Hara, the Carducci String Quartet and your classics (released: March 24, 2017), how did you achieve the right balance between rock and more traditional classical tastes?

IA: It was a bit of a vanity project, in the sense that I thought it would be one of those things I could tick off while I was able to do it. To work with a string quartet is, for me, not an original concept. We’d been working with string quartets since 1968 when I recorded a piece called ‘The Christmas Songs’ with voice, mandolin and a string quartet.

I’ve been doing that stuff for a long, long time and working with orchestras of different sizes and shapes; choirs and so on and so forth, but I wanted to do a ‘Best of’ Jethro Tull album in terms of picking some heavy hitters and realizing them in a more classical style of string quartet album.

That was something we worked on in the early part of last year and recorded it in September of last year and it was released in March of this year. It’s now an old project and not one I ever intended to take to the concert stage. Again, the logistics of organizing a tour with a string quartet…They’re all pretty busy doing their own recitals and concerts in the classical world. To try to find any time to do something together was proving to be very difficult within the few months surrounding the release of the album so we just decided that it was probably best not to go beyond the recorded work. It’s all back in history now, having recorded it a year ago but it feels like a project that’s done and dusted and put to bed. So on to the next things.

PB: You wrote something perplexing on your website, “I have a distinct dislike for poetry in general.” If you’re not a poet, then who is?

IA: Well, I’m never really sure what poetry is to different people. To me, it’s like a song without music. I’m not really a fan of poetry. I never have been. I occasionally read things. But I find that it all seems to be a bit self-conscious when you’re pontificating in verse. There is no music. There is no context for it. There’s merely the thoughts on the page. It’s not even spoken or sung. So. we don’t really know how Robbie Burns would have sounded, had he been reading one of his Scottish dialect poems from that era of poetic history. We don’t know what it would have sounded like.

We have no idea what it would have been like, listening to Shakespeare’s sonnets. We have no way to know. They’re just thoughts on a page. They seem, to me, rather isolated, rather poor specimens. Words without a home, whereas words with music does give context and, of course, we have the luxury in the 21st century of having the technology to allow us to make that available for posterity. And posterity, indeed, is a happy beneficiary of our tortured efforts.

PB: Historians enjoy looking back at an artist’s career, to draw conclusions about a body of work. Picasso’s “blue period” comes to mind. But critics can be pretentious, so let’s use you as our source. Looking back over the years, do you spot sonic milestones that speak to how you have developed musically?

IA: Well, in terms of the generic Jethro Tull, it can be a little confusing to the first time on-looker. When you look at the history of it all because we began, as many bands did, back in the late ‘60s, jumping on the blues bandwagon, because it was a way into music and playing essentially middle class, white man’s blues, which were usually a fairly poor derivative of the black American folk music, which the blues truly is.

Even before Jethro Tull, I remember playing that kind of music for a couple of years and then wanting to move on, trying to do something a little more original. That blues period gave away to what was dubbed in 1969 by the British music press as progressive rock music. We first heard that term; not “prog rock”, but “progressive rock.” It’s a more gentle and broader brush way of describing music that was, perhaps, more eclectic. It was drawing on different musical influences. It was developing the rock genre in not one, but many different directions.

So I was quite happy to be part of that vanguard of more developmental rock music and, of course, prog rock came when the press decided that that was a suitable description from a more ambitious, sometimes more symphonic or even operatic approaches to making complicated rock music, which was very often rather arrogant and self-indulgent.

Especially in the hands of the early Genesis or Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Yes; perhaps more than any other bands, they might be considered to be the top three exponents of that “showing-off” kind of music. So over a couple of years, I suppose, you would classify Jethro Tull as a prog rock band, but then it became in ’77, more of a folk-rock band, with ‘Songs from the Wood’ and ‘Heavy Horses’.

Other influences were corrected along the way, but I’d have to say that these days what I do is a mixture of all of the above, even going back, as I sometimes do from time to time, to perform some pieces from our very first album (‘This Was’). When you look back at a long career, it’s really drawing together all of those sometimes disparate music forms and styles and trying to bring them together in the context of a two-hour rock concert.

PB: Given the choice, would you prefer to collaborate with J.S. Bach, Igor Stravinsky or Ludwig von Beethoven?

IA: Well, I’d be scared to collaborate with any of them because these are proper musicians. I’m not a collaborator by nature, anyway. I find it very difficult to work with other people. I’m more than happy to play on somebody’s record if I like what it is they’re doing and if it’s well within my musical scope to be able come up with something that fits the music and is technically within my means, but in terms of sitting down and trying to work with Beethoven or Bach or Mozart, or whomever else you mentioned, that would be virtually impossible for me to do because I don’t read or write music in the conventional sense and it would be very difficult from a vocabulary point of view to do that.

I’ve collaborated, I suppose you can say, with a couple of Indian musicians, with Anoushka Shankar and Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, another classical Indian flautist, but I have to say that it’s always easy when you’re dealing with people who work in an improvisational way because you don’t really have to get into the detail of using words to describe musical ideas. When I work with orchestras, for example, I’m reliant on our conductor to be able to act as the interface between me and them, when it comes to explaining things or trying to put it into some context for them, to enable them to just read the dots on the page, so I think I would find it very difficult to collaborate in a sense with classical musicians and perhaps even with contemporary musicians. It’s just not something that fills me with a particular desire, really.

Having said that, my guests in two-days time—I have Loyd Grossman, coming up to play,

doing a couple of his songs in Durham Cathedral and Peterborough Cathedral, and Marc Almond, from Soft Cell, doing three of his songs with me. And Joe Elliott from Def Leppard is coming along to actually sing two of my songs in the Bradford Cathedral. So you can describe that, I suppose, as a collaboration, but it’s guest appearances. It’s not what I think you have in mind; you’re talking about the more creative process of originating some new music.

(Ian is mentioning these guest artists in reference to a series of ‘Christmas Jethro Tull’ concerts, performed on December 14-16, 2017).

I can’t write with other people. I just can’t do it. I’m just too self-conscious. I hate to have anybody anywhere near me when I’m writing songs. It’s just a very solo thing, something that is absurdly private, to the point of obsession.

I lock myself in a room and I can’t bear the idea of somebody’s listening to my words and music.

PB: You’ve been a great supporter of animal rights and an educator on related awareness over the years. TIME magazine recently featured an issue exploring the emotional lives of our best friends. In 2018, what can we do to make their lives easier?

IA: Well, stop eating them, I suppose, for a start. I’m not a vegetarian but I do rather limit my intake of meat. And I prefer fish. I find it easier from a moral perspective to eat fish than I do to eat cows and sheep and even chickens.

There’s a disagreeable side that goes on with all mammals. They obviously feel pain, quite similar to ours. I ascribe to their emotions. I certainly feel fear. Terror. They feel impending doom. And, of course, I’ve been involved in animal husbandry, particularly with fish, but also with sheep and cattle. I’m very reluctant to go down that route of rearing animals for food. But I think, perhaps, if we were going to be kind to animals by not eating them, we would be kinder to the human species, and even kinder still because of the vast reliance that people place on raising animals for red meat, depleting the planetary resources and cutting down trees to make huge areas for grazing cattle in various parts of the world and all of the bad stuff.

The Americans, the Brazilians, the Argentinians and the Australians are meat consumers to the point of absurdity. It seems like no one can go without one meal without eating dead animals. I find it quite absurd.

I find occasionally I will eat a steak or a piece of chicken or something but it’s something that I’m reluctant to do very often and my reluctance is as much because of the environmental issues surrounding livestock. Breeding for human consumption is as much that, as it is to do with the aspect of animal cruelty and animal suffering.

Arguably, there are some sheep in our fields right now. They’re not my sheep, but they’re grazing in our fields and they are all destined for the meat market. They are perhaps a little more fortunate than some other species of animals because they are roaming in wide open grassland with lots of natural food stuff for them to eat. They will feel the sun on their back or the snow on their back as they have for the last 48 hours. They are out there in the natural environment doing what sheep are born to do. Unfortunately, they’re also born to die, but they will have had a reasonably good life—they will have had an excellent life, while they’ve been alive.

Perhaps the killing of game for human consumption is a little bit more acceptable to me because there is something about animals that are out there in the wild, having a natural life. What I’m very uncomfortable about, is intensive farming when it comes to warm-blooded mammals.

Fish farming, I can go along with, up to a point. I’ve had quite a bit of experience with that, but the intensive farming of chickens, for that matter, or beef cattle makes me very uncomfortable with some of the practices that go on, and that is partly the reason that I don’t eat very much meat. If I do, there are plenty of sources of organically grown meat, that are certifiable that I would choose, if I were going to eat meat.

PB: Last time we spoke, you revealed, “They’re going to have to take me kicking and screaming” off the stage. Do you still feel that way about touring?

IA: Nothing has changed in the last year, particularly, to make me feel differently about it, but it becomes more and more inevitable with every passing year that my days are numbered and I don’t know what the number is, but I can’t even begin to guess, really. Hopefully more than a thousand, perhaps as much as three thousand. Who knows? But sooner or later, I’m going to have to call it a day. I’ll have to call it a night, even if I don’t go kicking and screaming. I’ll probably be gently deposited in a cheap hotel room and told not to return the following day.

PB: If you were to pass the baton to the next generation, what style of Ian Anderson-composed music would best satisfy the average teen’s tastes?

IA: It might depend whether it was a boy or a girl. An eighteen-year-old… It’s not that there’s necessarily a gender-specific answer, but I might be inclined, perhaps, just through gender stereotypes, to suggest, to a girl, “This might be more your cup of tea”… in terms of a subject that is more sensitive or on a subject that might be more approachable.

But if it were an 18-year-old guy, maybe I would make the assumption; however wrongly, that, perhaps, something heavier, more rock-like, might be the suggestion. But I think that’s what compilation albums are for; to draw upon a cross-section of music from a particular time.

If someone says, “What should I listen to?" I’d say, find something like (Laughs) ‘The Very Best of Jethro Tull’ or words to that effect and it will give you a carefully chosen cross section of music that record companies and I have decided would be reflective of the general musical styles of the band at that point when it was released. You can’t go wrong with a good ‘The Best of…’”

I don’t listen to a huge amount of music, but when I want something to listen to, it’s usually a collection of classical or jazz or blues. It’s usually a ‘Best of’. I let somebody else suggest to me, what might be a good balance of music to listen to, whether it’s, broadly speaking, symphonic music or folk music or blues, whatever it might be--I’m quite content to let somebody come up with a playlist.

PB: Ian, although you and your music have entranced the world at large, I’m guessing you might have some special feelings for the fans, living in your own back yard. Is there anything you’d like to say to the British audiences you’ll be seeing next year?

IA: Nice to see you again. It’s been a couple of years since we’ve been on tour. We have a few shows early next year which will be an opportunity, I suppose, to play the production tour, the 50th Anniversary Tour to mainly an older audience, which has probably been with us for a long time. The UK and the US and German audiences tend to be rather older. The demographic is kind of different. They’re loyal. They’ll stick with you. Of course, they’re getting on a bit now, whereas…

The Latin countries: Spain, Italy, Brazil, Argentina--places like that, we have a lot of younger fans in the audience who seem to be energised by perhaps that kind of retro phenomenon of rock music in its very creative period in the ‘70s. It’s a little different wherever you play.

But I can’t blame the UK audience for being nearly as old as I am. I only blame them when they leave their trollies and block the aisles of the supermarket fruit section. Then they’ll get a bit of a stiff talking to…

Bless them, they’re very nice. But what else would I say to them? Let’s just do all of us a favour on a cold and wet evening near a stage door or something. If you want an autograph, I’m happy to do it; just one. Don’t bring your entire record collection. Because you don’t have the time in life to stand there and do that and neither do I. And there’s somebody else waiting in the queue and I have to get back to my bed or up to the stage, if there’s a sound check.

I have just one request. If you want an autograph, then I’m honoured that you asked me, just the one. One person, one autograph. It’s a fair enough rule.

PB: I’ve stood in a line behind some of the fans with the fifteen albums…

IA: And the selfies, as well. Because they don’t know how to work their cell-phone cameras. And I’m not enamoured of those who want the quick photo. It always makes me feel a bit uneasy.

But there you go. I’m an old stick-in-the mud. I prefer to make eye contact with somebody and say, “Hey, great to see you. Thanks for coming to the show.” To me, that ought to be the exchange. Just look them in the eye for a second. I think that’s rather more important. There are such flimsy excuses for stimulating the memory, such as an autograph.

I do have one autographed photo, I have to admit, by Cliff Richard, one of the most famous and endearing pop stars. I have Cliff’s autograph on a photograph and it says, “To Ian.” Who could ask for more than that? A personalized autograph from Cliff.

I’m certainly not going to go hounding him to his dying day to request more autographs. I would perfectly understand that if I did such a thing, he’d say, “Oh, hi. Nice to see you, again. Now bugger off. You’ve got my autograph already.”

PB: Thank you.

Band Links:-

https://www.facebook.com/officialjethr

http://jethrotull.com/

https://twitter.com/jethrotull

https://www.youtube.com/user/tullmanag

https://plus.google.com/11327796081114

https://www.instagram.com/jethrotull_/

Picture Gallery:-