published: 9 /

7 /

2014

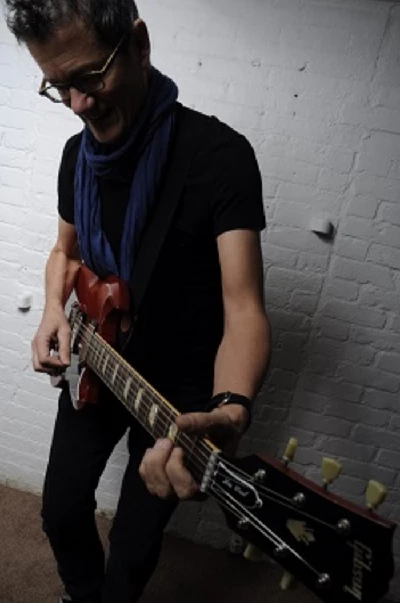

In the first part of a two part interview, both parts of which we are running consecutively, solo artist and Steely Dan touring and additional guitarist Jon Herington talks about working with Steely Dan...

Article

As an early music lover, Jon Herington picked up the saxophone and piano. Later on, he benefited from New Jersey’s tight-knit music community and with his band, Highway, opened for the up and coming Bruce Springsteen. He spent years as a session musician when he was asked to play complicated jazz arrangements on the spot. He also studied with several challenging teachers. It was his intricate group of original instrumentals recorded in 1982 and entitled ‘The Complete Rhyming Dictionary’ that piqued the interest of Steely Dan’s Walter Becker and Donald Fagen.

Initially, Herington was asked to play rhythm guitar for the popular band, but he was called back over the next few years to tour and do additional recording. Concurrently, he recorded his own solo albums. It was 2003 when Herington joined the ‘Everything Must Go’ tour. He also enjoyed working on Becker and Fagen’s solo albums – in this interview with Pennyblackmusic, he describes his delight when working with the longtime Steely Dan members jointly and individually on Fagen’s ‘Morph The Cat’ and Becker’s ‘Circus Money’. Herington also worked with Dukes of September, which consists of Donald Fagen, Michael McDonald and Boz Scaggs at the end of 2000.

He has also released ‘Time On My Hands,’ his third solo album, which features extended guitar solos and original ballads and blues numbers. A roster of talented friends and several collaborators assisted him. He also continues touring with Steely Dan, performing their greatest hits.

PB: Hi Jon. You studied guitar with Dennis Sandole, John Coltrane’s mentor. What did you glean from that experience?

JH: He was a fascinating, eccentric sort of guy. He was really a genius – a painter, a poet, a musician and actually most famous for his having become a teacher. I think I was a little young musically when I studied with him but he was the first guy who really got my hands in shape. He insisted on a really disciplined practice schedule. He wouldn’t let me work out any of his – what he called – literature until I had spent maybe eight months with technical exercises: scales, arpeggios and just a lot of real grunt work.

As I got older, I realised how unusual his literature was (Laughs), and really Coltrane was one of the few guys who actually made use of it in his improvising. Sandole was great for getting people to practice and he was sort of a maestro type of guy. He wasn’t your buddy. It was definitely the student-maestro division. But he was very advanced, and, even though he got everybody playing and practicing a lot, there were a very few number of people who were able to take advantage of his musical approach, the information that he would impart.

But he would fine tune and cater all the stuff that you would be working on musically too. It was all very personalised because he would listen to what you had absorbed, and he would create a new lesson for you based on what you had absorbed and what you hadn’t. He was a pretty brilliant guy that way, but I think had he lived longer and I had the time it would have been great to continue after I had become a more accomplished player. But it still was inspiring and he was eccentric and unusual and kind of funny actually.

PB: When with Highway, you opened for Bruce Springsteen in New Jersey. Did you sense then that Bruce would become so huge?

JH: Well, I certainly didn’t know how huge he would become, but he was huge for all of us growing up in that neighbourhood who were interested in music. He would play at our high school dances, and I knew three or four of the different bands that he had put together and that he had been working with, and he was a phenomenal performer even then and a great writer as well. He had charisma on stage. It was all there from the very beginning, even though the venues were sometimes as small as our high school cafeteria. It was definitely a thrill because he was somebody we really loved, but it also felt sort of normal for us because he was sort of a local institution and he played the same bars we played. He would hang out sometimes and it just felt like a very natural thing.

We took it in stride at the time and, of course, it wasn’t long after we had worked with him on one of the shows or two that he did his first record for Columbia, I think, and he was sort of off to the races. His whole show was a little less extreme because the parameters of the places he was playing were smaller and he wasn’t quite as histrionic and broad and bold with his performing, but it was powerful. He always went for it, and he was always a natural to me.

He was a huge songwriting inspiration for me as a kid. We were aiming for a similar thing at the time. It was really great.

PB: In the early 1990s, you were really steeped in the jazz world. You worked with Randy Brecker and you released ‘The Complete Rhyming Dictionary’ a while later and then recorded with Jim Beard, Victor Bailey and Peter Erskine. How did those players and the jazz itself inform your playing?

JH: That time was a particularly great one in terms of recording. Most of that came from being around New York at a time when there were still a lot of bands playing a lot of music that had been mostly promoted by a band like Weather Report. Pat Metheny was working a lot there. In a way, they all seemed like disciples of some of Miles Davis’ bands – they had gone on to make their own bands -- so it was Miles and Weather Report and all those followers of that kind of music making. It was before the smooth jazz thing really took off. And it was a much more adventurous, modern, vital sounding music but that phase was sort of ending.

I was lucky to be in New York and to get in on quite a bit of recording with Bob Berg and Randy Brecker, and almost all of those connections were from my buddy Jim Beard, who had worked with a lot of those guys live and had done a lot of producing and recording for those bands.

It was exciting to do that kind of work, and I had been working on that kind of thing for many, many years myself. ‘The Complete Rhyming Dictionary’ came about by being in New York at the right time and being associated with a lot of players and that theme. But it really felt like an ending to a musical era rather than a beginning. It wasn’t like after I did that record I decided to take that band on the road and try to work and get that music out. In a way, it was kind of the closing of a musical chapter because it just didn’t seem like it was the same market as before for that type of music. The smooth jazz thing was starting to take off and it didn’t appeal to me at all – it just didn’t feel right-- and I was beginning to rediscover my interest in songs and singing and writing, which connected more to an earlier time in my life, which turned out to be a very endearing obsession

.

I was starting to work with a little band of my own writing tunes and it was a vocal band, and it was a much more rock and blues-oriented thing than that instrumental music and especially that instrumental music that I made.

PB: What was it like transitioning from composing instrumental music to working intensively with a vocalist, like Madeleine Peyroux, in a stripped-down trio?

JH: The thing with Madeleine came a whole lot later. It’s funny. I started out as a player interested in blues and rock guitar. The British Invasion was what really convinced me that this was something I really had to do, but then when I went to college I became really interested in jazz because there was a lot for me to learn musically on guitar and it seemed like the best vehicle for allowing me to do that. You don’t really take that on lightly. It takes years of focus and practice. But once I got out of college and just tried to make a living out of playing the guitar I realised that I should reclaim the styles that I grew up loving and playing –in other words – increase my range and ability in a various number of styles in order to work more because I was interested in doing studio work and all sorts of variety -- it seemed like the necessary thing to do.

So Madeleine’s job was certainly different from many of the other jobs that I do. It’s the closest thing to a jazz job that I get to do. It doesn’t really feel like a jazz gig. It’s not a pure jazz gig. There’s a lot of pop and a lot of folk, so it’s a bit of a hybrid thing too. The difference in that case is it’s very quiet. We certainly do a lot of songs that are out of the jazz tradition. It required a different kind of approach, but it doesn’t feel at all unnatural to me because, after having made a living as a freelancer for many, many years and doing the kind of variety of work that I’ve done over the years, it doesn’t feel difficult to go that way for a month and do that tour and play it as appropriately as I can and then turn around and do the Steely Dan thing. It’s a lot louder and a whole different thing. There’s a lot of blues and rock guitar sounds. It’s not a quiet jazz guitar thing in terms of the sounds like Madeleine’s gig is.

When I do my job that’s different again. Instead of thirteen on stage it’s just three of us and it’s a very different role, plus I’m singing. I kind of thrive on the variety and if I didn’t do any one of those jobs, for instance, it would be a much less interesting year for me. I’d probably miss it. So even though there’s a strange sort of chequered development, as far as my musical history goes, because I’ve never really let go of some of the things that I’ve loved, not only have I tried to keep them all available to me to use when I need them, but also to find a way so I don’t sound schizophrenic. This can be as natural as that.

I’ve worked to try to do that and, as I’ve said, I don’t find myself in places where I find myself musically uncomfortable. It’s lucky but it’s a function of the good musicians I get to work for and with.

PB: It sounds like being a session musician can be demanding yet it also sounds like a great training ground for working with Steely Dan, a band that is known for its ambitious arrangements.

JH: For their early years, they had a sort of a set band of musicians. But very soon after the first couple of years, they began to employ studio musicians regularly on their records. There are a lot of different styles and sounds on their records, and it makes sense that the kind of player who can manage a band like Steely Dan is the player with some session experience. Everyone in the band is like that – some of them work much more than I do in the recording scene but that’s slowed down over the years.

All those guys are quite capable. They’re all good readers. They play in a number of styles and they’re just seriously trained and talented musicians. All those things are necessary to do a good job in that band and their standards have always been very high. It’s a hybrid of styles. There’s pop, there’s funk, there’s R & B, jazz harmony, but there’s rock and blues, especially in terms of the guitar sounds.

PB: And you’ve worked with Donald Fagen and Walter Becker on their solo albums. Was that a different kind of experience?

JH: It’s not completely different but it’s fascinating in the way it reveals individual contributions to the whole Steely Dan work. If you bother to just check out the lyrics to Walter’s writing alone, for instance, you really get a feeling for why Steely Dan’s lyrics sound the way they do, the really dark, film noir quality, the sort of characters that he creates. They’re even more concentrated and distilled on the Walter records, and when you hear Donald’s solo records there’s a quality they have of being a little more romantic and slightly more sentimental – never too sentimental. But they’re a little less ironic and certainly a little less dark. They’re a little sweeter.

PB: So, they’re a good compliment for each other.

JH: I think they’re a fantastic compliment, but I also love their individual records too and you get a slightly different take from each of them. You can certainly recognise them – in terms of Donald’s chord voicings, his interest in jazz sounds. You can easily hear a kind of signature quality about his solo records that really connects to Steely Dan records. They sound, at least, in some superficial sort of way, more obviously like, “Oh, yeah, this is Steely Dan,” plus he’s singing and he’s the voice of Steely Dan all the time so that’s a powerful thing.

If you really listen to a Walter record, it doesn’t take long to realise that his input in the Steely Dan stuff really steers it in a different direction and it’s a unique one, and the two of them together are hilarious. When you’re in the same room with them, like I am a lot, and you see the two of them start to joke around together, basically, everyone in the room shuts up because they’re so hilarious and so clever. They have a shared history of years and years of movie loving. They’re both big movie fans and jazz buffs so not only have they shared the last fifty years of pop culture history - and they were really great at absorbing it because they’re huge listeners, huge readers and huge watchers, but they also have known each other that long and worked together that long. It’s an unusual relationship (Laughs), and whenever they start going at it in any way everybody listens.

PB: What are the Steely Dan songs you most enjoy playing on tour?

JH: Lately I’ve been loving playing ‘Green Earrings’. I love the vibe of it and the way that it’s a fun hybrid for me in that it’s got a fun jazz style chord progression to play over, but it’s a rocker at the same time and the sound I use is sort of a rock sound. I always love playing ‘Black Friday’ because this band plays it really so well and it’s the closest thing to sort of a blues shuffle that we do. It always feels like an easy and fun and an open-ended vehicle for me.

But, as far as the songs go, I’ve always been a huge fan of ‘Third World Man’, because I think the Larry Carlton solo on that record is probably one of my favourites, if not my favourite pop guitar solo. And I love‘ Deacon Blues’ because it seems to sum up – I mean, if you had to tell a stranger in one song what Steely Dan was about I think I’d play them ‘Deacon Blues’.

PB: There is a compelling attitude that comes across in that song.

JH: The character is such a typical Steely Dan character in a way. He’s a loser – the proud loser in a way – he’s different and he’s flaunting his distinctiveness and wearing it. That’s a great one and it’s from’ Aja’. That’s their peak, I think. It seems to be the album that almost everyone looks to as their high point and I wouldn’t disagree.

Picture Gallery:-