published: 6 /

12 /

2012

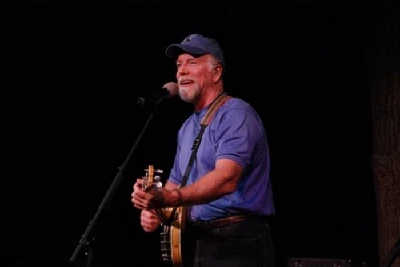

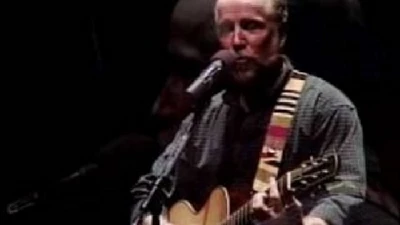

Lisa Torem chats to American singer-songwriter and political activist John McCutcheon about his latest album ‘This Land: Woody Guthrie’s America’, which is a collection of covers of songs by the American folk hero, and Woody Guthrie’s continued relevance

Article

John McCutcheon makes no apologies about his deep convictions, and hopefully his down-to-earth message songs will make people think seriously about justice. The American folksinger and author of the engaging ‘Welcome The Traveller Home: The Winfield Songs in 2004’ undertook his own walkabout in his twenties perusing Appalachia to document the trials of the area’s downtrodden and hopeful.

On his ‘Soap Box’ blog, this multi-instrumentalist, who plays everything from guitar to banjo to autoharp, questions the “demonization of the poor.” When he noticed that contemporary children’s music was full of cliché, he coined 1983’s ‘Howjadoo’. He’s made George Bush the subject of an original, socio-political song. A renaissance man; he has recorded thirty-four albums since the 1970s, proving through his prolificism that so many of his themes remain relevant today and that the players with whom he shares the studio and stage are also timeless.

Most recently, McCutcheon took on one of his favourite inspirations. By virtue of his compelling baritone, instrumental skills and riveting sense of history and popular culture, he has made an album that one beloved American folk hero might have been pretty proud of.

‘This Land: Woody Guthrie’s America’ includes the stunning craftsmanship of guitarist Tommy Emmanuel, the folk wisdom of Tom Paxton and the searing voice of Kathy Mattea. The songs range from Guthrie standards, sung by American school children for decades , and lesser known gems, which speak of human tragedy, that are equally poignant and musical.

To support the album, John McCutcheon is currently touring the US, finishing up in California early next year, and bringing to life those infamous lyrics about America’s unforgettable Redwood forest.

PB: ‘This Land: Woody Guthrie’s America’, which is your 35th album, sounds like it involved a great deal of research. Why did you choose the songs you chose and what makes these songs relevant today?

JM: The research was a combination of 45 years of marinating in Woody’s music and then some scrounging around amongst his papers at the Archives.

I chose the songs I did, first, because I love them and, second, because I didn’t want the album to be a “tribute album.” I figured there’d be plenty of those released this year and, also, because it gave me a chance to focus on his vision of America via his songs: as he said in ‘This is Our Country Here’, with “…as many good things as bad things.” It is not a typical way of approaching such a massive body of work, but it was also more interesting and hopefully more illuminating.

PB: You’ve worked with legendary artists on this recording. Can you talk about how some of them got under your radar and whether you had worked together before?

JM: Some, like Kathy Mattea, Tom Paxton, Tom Chapin, and Tim O’Brien, I’d worked with numerous times before and they’re good friends. Others were recorded in that most 21st-century way: emailing tracks around. Woody was the calling card. Everybody said yes.

PB: The album coincides with what would have been Guthrie’s 100th birthday. What topics do you think Woody Guthrie might have tackled if he were alive today?

JM: One of the things I wanted to do, both in song selection and presentation, was to show how contemporary Woody’s music still is. He hasn’t written a song in over sixty years, and we’re still dealing with immigration, workers rights, income disparity, etc. Sounds like today’s headlines, huh?

PB: ‘Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done’ provides an excellent introduction to the instrumental talents of the players. Can you tell me why you started the album off with this song and how you created the larger than life effect?

JM: It was really simply a fun way to get a lot of folks playing together. Most of it was done live and, especially for people like Tim, Brit, Bryn, and me, old time string band music is like falling off a log. The song was originally written and recorded in 6/8 time, so I simply hammered it into 2/4 and turned on the tape.

PB; On ‘Pastures of Plenty’ you feature your skills as a hammer dulcimer player. At what point in your career did you come across this instrument and how did you perfect your skills? Also, would you say that it is a particularly difficult instrument to play?

JM: It is the most recent instrument that I play in concert (I play a bunch of other instruments simply for my own enjoyment, never in public)…that was nearly 40 years ago. I’m still “perfecting my skills” as there is something new to learn all the time. It’s pretty wide-open territory because I know all the traditional guys, and they were pretty straight ahead tunes players. To expand the possibilities has been a lot of fun.

No, I would say it’s not particularly difficult to play. It is challenging to become really good at any instrument, however. But it’s set up diatonically and both hands are doing the same thing (unlike, say, the guitar or fiddle) and the instrument sounds great right out of the box the first time you try it out (unlike, say, the fiddle!).

PB: Another example of unique instrumentation appears on Fats Kaplin’s accordion in ‘Deportees’. Why the accordion?

JM: The song was about Mexican nationals, and I always thought the Tex/Mex accordion was key to giving it life.

PB: ‘Ludlow Massacre’ and ‘1913 Massacre’ are songs that are underscored by human desperation. In a world where light pop often dominates the airwaves, many audiences have not been exposed to songs that run so deep. How intensely have the lyrics affected you and what has been the audience response?

JM: Probably the things that affect audiences most are that they’ve never heard about these incidents. Our history books are full of blank pages of stories that should be told. Songs also have the advantage of taking contemporary stories (granted, both of these are historical…but all of history was contemporary at one time), and rescuing them from the ephemeral nature of our news culture. A great story on the news or in the papers today is forgotten forever tomorrow. Songs can be sung over and over and the stories retold and remembered.

PB: A few of the songs were left unfinished by Guthrie. How did you approach honouring this great folk artist when you tied up the loose ends?

JM: It was the most daunting collaboration of my life…and the other writer was never in the room. I tried to let Woody stay in the driver’s seat and figure out how to provide a little help in getting the story told properly. I was aided by years of being familiar with his writing and coming from the same sort of musical and political cloth. Hopefully I helped do the songs justice.

PB: You mention that you grew up learning some of Guthrie’s material, but that it wasn’t until later that you discovered he was the composer. For someone getting to know your music, what should they know about you as a writer, performer and citizen?

JM: If I have done my job, the songs will tell them everything they need to know. The job of the writer is to try to tell the story and then get out of the way.

PB: On ‘Hobo’s Lullaby’, you perform a duet with Tommy Emmanuel. This is the one song on the album, which was not written by Guthrie. Had you worked with Tommy Emmanuel previously? How did you achieve the sound you both wanted?

JM: I included the song because it was Woody’s favourite song. Also I love playing this song. Tommy and I are old friends and have frequently crashed one another’s sets at festivals. We had wanted to work together for a long time, but our respective touring schedules prevented it. We found a day we were both available, met at a studio, set up a couple of mics, sat across from one another, and went at it.

PB: This album was your first recording of covers. If you go back into the studio, will you record another album of covers or return originals?

JM: I’ve already written another album of original songs. I can’t really say whether I’ll do another album of covers. The Woody album seemed so natural and I’d thought about doing one for years. The centenary this year finally gave me a perfect excuse to do it. But another? Maybe I would do an album of Si Kahn songs (though we’ve written lots together) or Pete Seeger stuff. I am only interested in doing things in which I feel like I can say something new and/or interesting.

PB: Last year you covered a great deal of the US on your tour and you played many intimate venues: coffee houses, churches and libraries. What is on the agenda this year?

JM: More of the same, really. Plus Australia.

PB: If you could have tea with any character from a novel or movie, who would it be?

JM: Atticus Finch.

PB: Thank you.

Picture Gallery:-