published: 28 /

8 /

2011

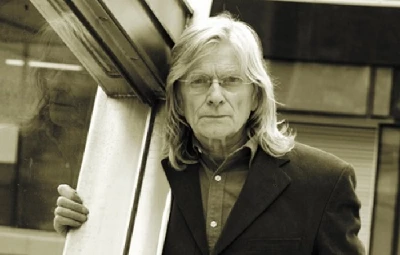

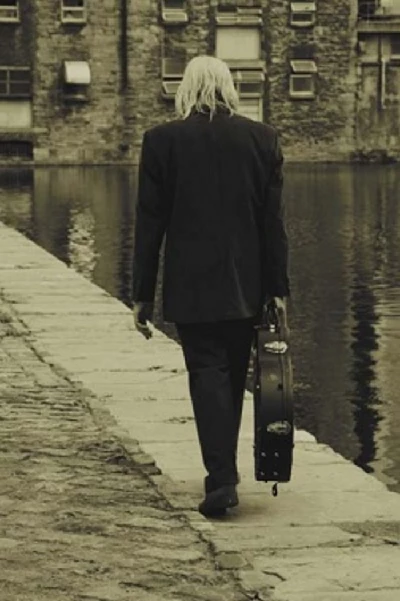

Henry McCullough, the one-time guitarist with Wings, speaks to Lisa Torem about working with Paul McCartney and his album 'Unfinished Business', a collection of covers and original material, which has recently been re-released

Article

PB: Hi Henry. Which area in Ireland are you from?

HM: I live in the north; near the Giant’s Causeway.

PB: That’s a spectacular area.

HM: Nobody here has ever heard of it.

The Giant’s Causeway consists of thousands of basalt columns, weathered by centuries of volcanic activity – these columns form gigantic steps, which rise mysteriously from the land and beneath the sea – and have inspired a myriad of fables.

I guess there are not too many geologists here today at this year’s annual Fest for the Beatles (held in Rosemont, Illinois), but perhaps some fan might have heard of Bushmill’s Distillery – it’s a great place to grab a pint and is only steps away from the famed World Heritage Site.

Like the Giant’s Causeway, Henry is a natural wonder. Despite decades of performing with some of the most famous acts on earth, and having a unique style of playing which incorporates folk and riveting blues, he is humble and gracious. He is eager to answer every question that I ask him.

I was lucky enough to catch this guitarist/songwriter for an in-person interview after his completion of several signing sessions and panel discussions.

“Am I talking too much?” he asked me, sincerely, in his soft-spoken dialect, as the tape rolled.

Though this is his first trip to the US in several decades, he has never stopped performing.

Henry McCullough originally played in Dublin with the quartet, The People. In the late 1960s, a move to London meant a name change to Eire Apparent. That band got signed by Chas Chandler - Chas was the legendary bass player of the Animals who, after becoming a manager, took a chance on a young Jimi Hendrix. Eire Apparent’s first album was, not surprisingly, guitar-driven psychedelia embellished by sweeping harmonies.

Henry found himself, in 1969, with Joe Cocker and his Grease Band at Woodstock. He never got to mingle with the hippies as the helicopter flew the musicians immediately back to their Holiday Inn. Henry, however, not only tore through emotional guitar solos, but he contributed some fab falsetto to Cocker’s infamous cover of ‘With a Little Help From My Friends’.

Then Wings drummer, Denny Seiwell, introduced him to Paul McCartney. The talented guitarist toured with Paul McCartney and Wings for eighteen months and made major and memorable contributions to the ‘Red Rose Speedway’ album. The band, during those early days, stopped in randomly at local universities to test out new material – getting looks of disbelief from startled professors and students.

Henry’s release, ‘Unfinished Business’, a combination of covers and his own material, originally came out in 2002 and has just been re-released. It is a tribute to artists that deserve attention. Henry toured with Frankie Miller; an outstanding vocalist who did not receive nearly enough attention in the US, but was well-known in the UK.

He unearthed an early Dylan song, ‘Ballad of Hollis Brown’, about a farmer in the Dakotas whose life takes a sharp, violent turn. Henry also pays homage to his wife Josie as she tends to the flora: ‘Josie’s in the Garden.’ But, one of Henry’s songs, ‘Failed Christian’, struck a very personal chord – even in total strangers.

“I’m a failed Christian/I don’t go to church/I smoke and I drink and I lie and I curse.”

Though Henry McCullough might have failed at being a Christian - in some folk’s eyes – (give him a moment to explain, please) - he’s a dynamic success at everything else.

PB: You have just finished recording ‘Unfinished Business.” You’ve made some interesting choices in term of selecting cover material. For example, ‘The Ballad of Hollis Brown’ was recorded by Bob Dylan early in his career. It’s about a very, desperate man.

HM: Many of the songs were a tribute to the people that I’ve worked with; I’ve toured with some of them such as Frankie Miller. I was always a fan of Bob Dylan from the early days. I wouldn’t listen with intent. He was changing the world, writing great songs and good lyrics. But, it was also a tribute to Paul and Frankie. So, that’s what it is.

It was great to do it. I just did it in the way that I wanted to do it; the tempo of the songs – There is a cover of a Frankie Miller song – ‘Drunken Nights in the City’ – on the album which is a little bit different than the way his band had done it. It was the same with Paul; (‘Big Barn Red’ from the Red Rose Speedway album) it was the same song, but I did it a little bit differently. It was a nice release.

PB: Back in the Eire Apparent days, the band did a song: ‘Yes, I Need Someone.’ That album is now considered “psychedelic rock.” The arrangements were pretty wild for the time. Of course, you were under the influence of Chas Chandler and Jimi Hendrix. But, I still hear some of that unbridled sound in arrangements you created for Paul McCartney and Wings. Would you say you have gone in a totally different direction stylistically, since then, or has there been a common thread in your arranging?

HM: Well, I’m not really sure how to answer that. To sit down and copy some of the songs, note for note, is kind of like karaoke. I respect everybody who plays music, but some people say, “This isn’t so good and that isn’t so good” – not what I play, but you have to take it for what it is. It’s just me own version of it.

Of course, I grew up with all these people: Fats Domino, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. I was a huge fan, but it wasn’t done on purpose. Like ‘Big Barn Bed’ – I was sitting around the house, at the time. It sounded like something, but I couldn’t remember what it was. I started singing along and I said, “Oh, I’ll do this.”

I didn’t sit down consciously and say that I’m going to use this style or that style. It just happened out like that. It doesn’t happen on purpose. But, I was looking at the songs from an outsider’s point of view.

PB: But those artists that you’ve just mentioned as inspirations were all pianists. Is the instrument less important than the riff?

HM: You cannot do a Fats Domino song without putting in a saxophone. So, that’s what I did (Sean McCarron plays sax.) I played the ‘Unfinished Business’ songs on my own for a long time, on my own, you know?

I meant to do this on my own – it’s really expensive to make an album. 40,000 pounds…I didn’t have that sort of money to spend. But I never get the financial rewards back from it because I don’t have anybody who does distribution and who works at the business end of music. I shy very much away from that and I’m happy enough to live with it like that.

PB: Is that because you want to maintain your artistic freedom?

HM: I’m not that good. I never, ever thought about it like that. It just turned out that way and it has more to do with the people I’ve worked with. I didn’t say to Frankie Miller: “let’s do: ‘Drunken Nights in the City’.” It’s a great song. Fats Domino was a great rock and roll player. I didn’t think about it before. It was only afterwards that I realized that these songs were part of me history, as well.

PB: Henry, in the 1970s, you ventured into the area of studio production with an artist named Rosetta Hightower. Was that a one-off project? Did you think about producing other artists after that or was that experience enough?

HM: It was enough. To produce for other people – I didn’t exactly have the experience. It was just a melody – that’s the way it was done and that’s the way I looked at it. It was just a melody.

PB: How did you get involved with George Harrison’s Dark Horse Label? George had produced artists like Ravi Shankar and had a quite, limited roster.

HM: I was on the road and I had recorded the ‘Mind Your Own Business” album, my first solo album which came out in 1975. I didn’t have access to people who knew how to distribute the stuff. George got to hear one of the songs and he gave me a call. I went down to the studio and he said he’d like to put my album out and I said okay.

He took it to a distributor and all of the rest of it. But, at the time, he was in court over his song, ‘My Sweet Lord.’ (Harrison was in court because the melody of ‘My Sweet Lord’ was said to have been the same as that of the song by the Chiffons, ‘He’s So Fine’-LT.)

George went to court and lost the case and had to pay at least six or seven million back to the people who had written it. So when he lost that case, Dark Horse folded and that was me, at the losing end.

PB: Let’s get back to how you come up with some of your unique sounds - that riff on ‘Poor Man’s Moon’?

HM: You sit in the house and you play around and, all of a sudden, you get this idea.

(Henry mumbles some melodies under his breath.) Several of the songs on the album remind me of the Grease Band days. I like to have only one chord. You can get so much out of that one chord. If you listen to some of those African bands – they don’t change chords. If you get it right, you get a bigger feeling from it than when you change chords.

With ‘Poor Man’s Moon’, I had the riff, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with it. I went into the studio and the engineer said, “Are you ready?” I said I was, but I had no idea what I was going to be singing. I had the riffs, but I didn’t have any lyrics. It was just done there and then. I breezed through it really.

PB: Isn’t that what happened when you recorded ‘My Love’ for Paul McCartney and Wings, on the ‘Red Rose Speedway’ album? There was a spontaneous magic that happened on that solo.

HM: It doesn’t happen all of the time. We did it in one take – which scared the life out of Paul.

PB: Is Paul a more structured person?

HM: I didn’t want to play what Paul had suggested. It had happened with George Harrison. George had sat in and said he’d play whatever they wanted him to play. But, I couldn’t be as much a member of the band.

George Martin was in the control room. He asked me what I was going to play and I said, ‘I don’t know.’ There was a fifty-piece orchestra. I did it in one take, which was unusual. I might have made a mistake, which could have been fixed within the first, four bars. I closed my eyes, the orchestra played along – and from the control room there was silence.

With music, sometimes you come across something and it’s a gift from God and it’s channeled through you. I swear, I never heard those notes before that way. My career wasn’t on the line, but I knew that if I’d gotten it wrong that I’d have to accept the fact that I didn’t do it in bits. But it’s captured there and sometimes I think that’s the best way to get it - if you capture it right.

To capture it like that, from beginning to end – it’s not a long solo – and Paul didn’t like the way I did that (Henry is referring to the improvisational way it was done, not the finished product-LT), but I assured him…

I went to see Paul when he performed in Dublin. I hadn’t seen him since 1973 or 1974. He knew I was coming down, so he gave me a big hug and kiss afterwards. He said that no matter where he goes, he couldn’t help bringing up this Irishman whose solo had been perfect for the song. He felt that the solo on ‘My Love’ was special.

I don’t know any other kind of solo, which would have worked on that kind of song. I think it hits the song as well as any other song by anybody – that’s why I was delighted to be in the studio. I left with a happy heart because I had shown Paul that this could be done, this way, but I was dead lucky!

When some people meet me, they don’t even ask me how I’m doing. They say, “Hey, man,” and they talk about that solo– because I’ve made my mark on that song. You couldn’t write a solo for that song – it had to be captured like that. That’s the power – you can’t touch it and you can’t change it. I did it for Paul.

PB: Now, in performance, when Paul tours with Brian, Abe, Wik and Rusty, ‘My Love’ is performed with a set solo.

HM: Yes, and I’ve heard it played, note for note, by saxophone players. Musicians have played it exactly as I had done it – sometimes they get it a little bit wrong – I got it a little bit wrong. I just bypassed that first note. But, the second note made up for it. It’s hidden in there, a tiny little mistake – but, only you and I know about it (Laughs.)

PB: Many musicians have commented positively on your tone. Can you describe what that means?

HM: There are tone controls on the guitar. I don’t use pedals at all. People say that I’m from the “old school.” I just readjust the volume or something. By doing it like that, I’m consciously aware of how my right hand strokes the notes. You develop a kind of sound and tone of your own.

Even if you use the plectrum, there’s a connection between this hand and that hand, and if you do it, unconsciously – which I do, you know, I’ve developed a way of working. You just touch the string and that’s what the tone thing is all about. I’m old-fashioned and I’m too old to change.

PB: Was ‘Belfast to Boston’ based on real-life experiences? (This track had been previously recorded on the 2001 ‘Belfast to Boston’ album.)

HM: I was touring America with Joe (Cocker and the Grease Band) in the 1960s. I met people and there were a lot of drugs about; mostly weed and mescaline and stuff like that - that was the 1960s and I wouldn’t dare do that now.

I had a ticket to Boston. It was about being in the band, meeting an Apache and taking peyote.

PB: You have written such beautiful images; and, at the end, you invite us to be tucked into your pocket…

HM: I just love you and I’ll take care of you..

PB: You wrote: ‘Ould Piece of Wood (The Loss of the 335)’ about a special guitar of yours which got stolen.

HM: It was a Gibson guitar, model 335, which I had bought in 1963. I had had it for 32 years. I had cherished it and it became my own. We had developed a relationship and I was never too far away from it – through the good and bad times. I never forgot that guitar – it was my partner in crime.

I was with the Polish musicians that I was working with. After the plane ride back to Heathrow, on a British Midlands flight, I went to the baggage area and there was no guitar. I spoke to the people in charge and they said not to worry – that it would be there. They said they would get it to me, in the morning, by taxi. They brought the suitcases and I asked about the guitar. It never arrived.

Six weeks later a guy calls me up and says that my guitar was on sale. He called me from one of the best known guitar shops in the UK. I called the owner and introduced myself – he told me the guitar was in the window.

On my guitar was a painting of a woman – I had met the artist, John Napper, through our interest in folk music. (Napper, in the 1950s, had been one of the British Royal Family’s portrait painters and had also designed the inside cover of the Grease Band’s debut album-LT). On the painting, there were a couple of shamrocks and flowers around the controls. John had created this with that blue light that shines – fluorescent light.

There was a horse’s head on the top curve. It was like a Greek-style, horse’s head. It was squared off and on the bottom was a semi-naked lady. I used to use this little blue light and I would light it up.

So, I said, “You had my guitar in the window. Can you tell me where it is?” He told me that this guy had walked in off the street with my guitar and asked him if he could put it in the window, so he put it in the window.

I said, “Hold on a minute. Some guy you don’t know walks in and says he’s got my guitar and you put it in the window?” And, do you know what he says to me?

“Henry, I didn’t know where to find you!”

I said that this was ridiculous. I got a hold of the law. They were useless – I had asked them to sort this out. I was told, “Leave it with me. I’ll sort it out.”

I called the shop a few days later and told them that I have the police on the case. The guy told me that “the guy” came back, a few days later, and took it.

I asked him if he had gotten the guy’s forwarding address. He hadn’t gotten a phone number, no nothing. They stole my guitar and it went underground. I swear to God. I hate to talk about people in the music business, but that shop stole my guitar and then it went underground.

I never saw it again and I cried bitterly. I sat on the bed with a heavy heart and I thought about all these years with that beautiful guitar, and some asshole takes it into a guitar shop and has all these lies told about it.

I’m too old to tell lies, but when you’re confronted with people in the business, that tell you lies - I put me head in me hands and I knew it was gone. It never resurfaced after that. I bought a similar model in Belfast but I couldn’t get out of it what I was getting from the other one.

PB: What prompted ‘Failed Christian?

HM: When I was growing up, my mother took me to church for the evening service. She was spiritual, but she didn’t go to church all of the time. But, I couldn’t figure out what it was all about. There was this man that you couldn’t see, but he’s there all the time. Your mind isn’t ready for it. Then, after fifty years of age, I realized what the whole thing was about.

When I went to church, back then, for the evening service, the choir started. They passed around the collection jar and if I saw half a pound or a six-pence, I would take it – anything for a bag of sweets. The choir would be singing all these harmonies and it would scare me half to death.

On the way to the studio, I got this feeling I’m going to meet my maker. If I go to hell, you’re going with me. There were things I had seen with me own eyes and I felt I was contributing more to the spirit of things than these people ever did.

Nick Lowe covered it and so did Dave Alvin and an American gospel group, Over the Rhine. I’m very picky about how I put a song together. I use very simple chords and stuff. It wasn’t a thing that I would have dwelt on – it just came out, that song.

But, I got more letters about it – people started talking about it. I have a sister who can’t even say ‘Failed Christian’. She can’t even say it. People think that you’re not owning up to God and Jesus and that I think I can do exactly what I want – but, it’s not like that at all. It’s just a different way of looking at it.

PB: It’s interesting that other songwriters wanted to cover it.

HM: Nick Lowe asked, would I mind if he covered it. The only thing is, he said, you can’t put out your arrangement until six weeks after I’ve done it. He wanted to do his own version of this song.

A preacher wrote me a four-page letter about the song. He said, “Henry, I’m worried about that song you wrote about a failed Christian.” He quoted the Scriptures to me. So I sat down and wrote him half a page about the drums and the trumpets and everything else. I still have that letter at home. He wrote me back again and said, “I was scratching where I wasn’t itching.” All of that surrounds the ‘Failed Christian’ song.

But, then a minister got in touch. He was preaching from the pulpit about being a “failed Christian.” He said, “I just want to let you know that.”

PB: That song has gotten a lot of mileage.

HM: And, I owned up to stealing from the collection plates. But, after that church service was over, I didn’t know what they were talking about. But, now I’m a great believer in a higher power. But, I couldn’t have done that song when I was 20 or 30 because I was taking mescaline and all kinds of drugs. But, eventually I got back into the studio and realised now is the time for this.

PB: How aware are you of your effect on the audience as you perform live?

HM: There has to be that connection.

PB: Do you think about it when you’re on stage?

HM: I never think about it. But, I know, from experience that you try things that you would have never tried before. When this thing happens between the music and the people that you have listening to it – it makes you take a chance that maybe you wouldn’t take if you were tired.

There’s an invisible thing that connects you to the audience. It doesn’t come out all of the time. But, you never drop below a certain level, so the people wouldn’t know if you’re not interested or that you’re too tired, because the music is good enough for them.

But, when you get it going, it’s spiritual as well.

There’s this connection – music, I think, is the greatest art form of all. There’s Picasso and the art world – but I can’t see it. Music can make you laugh, it can make you cry and it can bring you to your knees. I don’t get that from any other art form, but I don’t know about art. It’s the music that has been with me since I was born.

I’ve been playing music since I was about eleven or ten ,and it’s not always easy. You do things and sometimes it’s not financially worth it, but you do it because this is what you do. You can do different gigs for nothing, because of what’s created by you and the audience. But, like I said, you can’t do anything about that because it appears out of the blue.

PB: Thank you, Henry.

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:-

|

|

477 Posted By: Lisa Torem, Chicago on 06 Oct 2011 |

Hi Cal Donia,

Yikes!! I'm so sorry about that misinformation and my apologies to Frankie, of course, too!!

I'm glad to know, though, that he is currently living in London and receiving the respect he clearly deserves.

I agree that Frankie has an incredible legacy and admire intelligent artists like Henry McCullough who appreciate his talents, as well.

Thanks for your timely comment!

Best Wishes,

Lisa

|

|

476 Posted By: Cal Donia, Northern Ireland on 05 Oct 2011 |

In your Henry McCullough interview you mention Henry working with "the late Frankie Miller."

It would come as a big surprise to Frankie to know that he is dead - he isn't !! Frankie suffered a brain haemorrhage while in New York in 1994 & was very ill for a long time but he now lives in London & has continued to recover. He has written some material since &, even though he won't be able to perform again he's still out there & a much respected man; a really exciting live performer, a highly respected songwriter & man whose recorded material is still superior to that of many of his contemporaries.

|