published: 24 /

5 /

2006

Best known for his role as a record producer and for his work with the seminal Talk Talk, Tim Friese-Greene now has his own musicial solo project Heligoland. John Clarkson talks to him about his career as both a producer and a musician

Article

Tim Friese-Greene is best known for his role as a record producer in the 80’s and the early 90’s, and especially for his work with Talk Talk.

Friese-Greene began working with Talk Talk, who had started out their career as one of the many New Romantic-era synth pop acts that dominated the charts in the early 80’s, at the time of their second album, 1984’s ‘It’s My Life’, and soon developed a unique songwriting partnership with the band’s singer Mark Hollis.

While the lush-sounding ‘It’s My Life’ was essentially a pop album and spawned massive hits across Europe with ‘Such a Shame’, ‘Dum Dum Girl’, and its title track, its follow-up, 1986’s ‘The Colour of Spring’, from which was drawn another big hit ‘Life’s What You Make It’, found Talk Talk abandoning their synthesisers and proved more experimental. Described by one critic as being like “an easy-listening version of Can”, it was more acoustic in tone and had the group experimenting with both an adults’ and a children’s choir and also a more orchestral sound. Talk Talk’s final two albums, the gloriously mellow ‘Spirit of Eden’ which came out in 1988 and its more feedback-dominated successor 1991’s ‘Laughing Stock’ both ran to six extended tracks each and, early and pioneering influences on the post-rock movement, found the group moving increasingly into modern classical and free-form territory.

As well as Talk Talk, Tim Friese-Greene also worked as a producer with acclaimed independent bands such as ethereal guitar-rockers Lush and shoegazers the Catherine Wheel, as well as more commercial chart acts such as Thomas Dolby and one-hit wonders, Tight Fit, whom had a No.1 hit with their single ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ in 1981.

Always a restless talent, Friese-Green wearied of doing production work in the 1990’s and abandoned it to concentrate on his own solo project, Heligoland, with whom he has recorded an EP, 1997’s ‘Creosote and Tar’, and two albums, ‘Heligoland’ from 2000 and this year’s ‘Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie’. All have come out on the small label Calcium Chloride.

In contrast to much of his previous output, which was rich in detailed atmospherics, Heligoland surprisingly has a lo-fi and scuzzed-up, rugged blues sound. Friese-Greene’s original main instruments were the keyboards and organ, but both the EP and the two albums have him playing a five-string guitar and tackling vocals for the first time. The lyrics of ‘Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie’, which appear hand-written on the booklet that accompany its CD, suggest a want for personal freedom and seem to rail out against the dumbing down of society.

Pennyblackmusic spoke to Tim Friese-Greene about both his career as a producer and his evolvement and growth as a musician and songwriter.

PB : You first began working in the music industry back in the mid 1970’s. How did you first become involved in music ? Were you interested in sound and engineering from an early age ?

TFG : It wasn’t that early. I had a friend who worked at Air Studios as a tape operator and he took me down for a visit one day shortly before I left school and I became totally smitten with the whole idea of working in a studio. I had been listening to music for years, since I was 11 or 12, but I just thought the whole idea of the sounds you could get out of these huge speakers and how you could adjust and change parameters was fantastic. From that point my course was set.

PB : You initially started out at a place called Wessex Studios in London as a tape operator, didn’t you ?

TFG : That’s right. It is now gone.

PB : The role of tape operator also no longer exists. What did that involve ?

TFG : It really involved exactly what it says it involved. Remotes weren’t really invented until the late 70’s, so you used to have a tape-op sitting on a chair next to the engineer and the 24 track, pressing rewind, forward, stop, and play. Generally these machines didn’t have tape counters on them, so you had no way of knowing where on the reel your first chorus was or your second verse. What you used to do was look at marks revolving on the tape. To be able to move around efficiently and to anticipate where the producer wanted to drop in was an art in itself. It was a job that demanded a great deal of concentration. I took it very seriously and I was a good tape-op.

PB : You moved from that into engineering and production . How long did that take ?

TFG : It was very quick. If you had what it took to be an engineer which was decided by the studio boss, the tape-op was usually a temporary position. The idea was that, as you would be doing your job, you would be watching what the engineer did, thus allowing you to move into his shoes when he moved on. That happened very suddenly for me. Two engineers left Wessex virtually at the same time and so I was shoved upwards to plug the gap. It was a relatively short apprenticeship.

PB : Was it a job with good career prospects then ?

TFG : It could be, but it wasn’t always that way. In some studios there were often a pair of studio engineers who weren’t terribly ambitious and who wanted to be engineers all their lives. They could be there for decades. If you were a tape-op in a studio like that, you could be left with the choice of sitting in the studio and hoping that one or them would die (Laughs) or taking the plunge and moving on to another studio where you might get a better hit rate. I was very lucky at Wessex, but I can think of any number of people who just stagnated in their studios because of their inability to move on. It was very much a lottery.

PB : You initially became known in your work as a musician as an organist and a keyboardist. Were those instruments that you learnt as Wessex or did that come before that ?

TFG : I started playing piano when I was about 11, but I never considered it as any kind of career, mainly because I never thought I was very good. I did get a lot of fun out of it, but it was totally superseded by my love of working in studios. All the time I worked in the studio as a tape-op, an engineer and then a producer, I treated keyboard-playing as a hobby. I started playing on peoples’ records quite by accident. My first appearance on a record was in 1977 on a 999 single, which was produced by Martin Rushent.

PB : …Which is a claim to fame in itself really.

TFG : Well, indeed ! (Laughs) That was the first one. I used to play very sporadically on bands’ records in those early days. There was a Hammond at Wessex and a fantastic grand piano, and I used to play around on those quite a bit. I never used to take it at all seriously though.

PB : You had a massive hit in 1981 with Tight Fit’s ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’, which got to No. 1, and their ‘Fantasy Island’ album, both of which you produced, Who else of note had you worked with as a producer up until that stage ?

TFG : There were all kinds of peripheral bands. There was a band called Blue Zoo. They were on Magnet, and they had a hit with a single called ‘Cry Boy Cry’, which got to No.20 in the charts. All the hits I had happened around at the same time that Tight Fit were in the charts. I also produced Thomas Dolby’s EP ‘She Blinded Me With Science’.

I spent a couple of years in New York as well, working with some of the post punk bands over there. One was called Quincy. Dirty Looks was another. I used to do a little bit of Stiff stuff, but there was nothing very major. I never really felt that I was being given the A list .

PB : Did ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ help to push your career forward ?

TFG : No, not at all because Tight Fit had no credibility at all. If I had wanted to cash in on Tight Fit of, then I would have had to work with all sorts of bands that I didn’t want to do. It is always nice to have a No. 1. I was down at the Venue in Victoria when it was No. 1 and everyone was dancing around and buying me champagne, but I found it very hard to get excited about it. One of my big issues at that point was that I wasn’t really getting the bands that I wanted to produce and I didn’t really see how Tight Fit being No. 1 was really going to further my cause. It was more a thorn in my side than anything else. I just knew from that point onwards that being offered the stuff I wanted would prove even more difficult.

PB : How from that did you become involved with Talk Talk ?

TFG : Mark Hollis had noticed that I had had several records in the chart, the Tight Fit one, the Blue Zoo and the Thomas Dolby one. According to him, what made him in get in touch with me was that none of them sounded alike, and, therefore, I didn’t have a signature sound. I think that was quite important to him. Some people like producers who have identifiable sounds. You can think of plenty that do. Trevor Horn, for example, is one. Others, however, don’t. I had never been into the idea that I should have one.

PB : What was the appeal to you of them ?

TFG : I am not sure there was an appeal to me actually. There was nothing remarkable about Talk Talk at that point. I thought their first album ‘The Party’s Over’ was okay. I didn’t particularly rate the song writing at that time, but I thought that Mark sounded okay. I took it on because there was nothing else around that I wanted to do more at the time, and there was nothing I disliked more than not working at that stage.

PB : You were co-credited with half of the songs on ‘It’s My Life’, and then all the songs on the three subsequent albums. How much experience of song writing had you had by the stage of ‘It’s My Life ?.

TFG : Very little ! I had co-written things with other people, some of which had been published and some which hadn’t. Mark didn’t have enough material for the album. We both clicked quite well at an early stage and he suggested that we try and write together. I would never have had the temerity to do so myself, because it is not a thing that a producer does, puts himself forward as a co-writer. It would have been pretty lairy. We used to write on a piano in the front room of my house at the time. I obviously felt that I could deal with it though. I had had a bit of experience at song writing, but nothing particularly major.

PB : You’re often credited as being the “unofficial fourth member of the band.” The band toured until 1986, but you never actually toured with them. Is that right ?

TFG : Yes, I never did. I played one gig at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1986, but that was all I ever did.

PB : Were you ever actually officially a member of the group ?

TFG : No. I was very clear from the beginning that I didn’t want to be a member of the band, even though I was asked to. I knew that there would come a point in which I would want to officially walk away from it and I wanted to be able to do that without any strings attached, so I was very careful to keep my autonomy. I knew that if I was ever officially a member of the band then I would feel that my role would have to change and I would have to demand more say in musical direction. When I was the producer I was happy to respect the sovereignty of the band i.e. Mark in terms of what it did. To work it had to accommodate his world view if you like. That is what I saw the producer’s job as being. I thought that it would be very dangerous for me to see myself as a band member because I felt that it would give me extra rights and would create difficulties.

PB : The band, however, for all intensive purposes, really stopped being a band in 1986. It evolved into something far beyond that. Would you agree with that ?

TFG : I think the thing that made it marginal as an outfit was the fact that Mark decided after ‘The Colour of Spring’ that he didn’t want to tour anymore. That made it very difficult for the other members. After ‘The Colour of Spring’ we dispensed with other keyboard players totally, because Mark and I thought between us that we could cover that base and we did. Mark and I had such a good understanding that it was source of continual frustration to us that we had to constantly explain to other musicians what we wanted. In the end we would just shrug and say “We will do it then”. We started to play more and more of the stuff ourselves and to cut out the middle man. We didn’t have to verbalize so much that way to get people to understand where we wanted to go with it, and to some extent that became the case with the other instruments as well. Neither of us could play drums, so Lee Harris (Talk Talk’s regular drummer-Ed) was always dragooned into playing drums when they weren’t done synthetically. Paul Webb (Talk Talk’s bassist-ed), fell beside the wayside after ‘Spirit of Eden’. Mark even played some of the bass on that though if I remember rightly.

PB : How did you and Mark write songs after 'It's My Life'? Was it mainly through improvisation ?

TFG : It changed from album to album. On ‘The Colour of Spring’ we started off with loops, generally arrived at on the Fairlight II which I had just bought. ‘Spirit of Eden’ was largely written on a drum machine. We then replaced it with Lee, whereas on ‘Laughing Stock’ we started with drum patterns that came from Lee playing them in the rehearsal room. We then wrote the songs around the drum patterns that he came up with. All of the three major albums started in different ways.

PB : One of the fascinating things about Talk Talk is that there is no real pattern there. Each of their five albums could be by five different bands really.

TFG : Yes, I would agree with that, although to some extent I see the leap between the last two as being smaller and them having some similarities. I see ‘Laughing Stock’ as being a refinement of the whole of the ‘Spirit of Eden’ aesthetic really. Phill Brown, who engineered both those records, and I sat down before we did ‘Laughing Stock’ and we discussed some of the things that we didn’t like about ‘Spirit of Eden’ and in what way we would like to rectify them on the ‘Laughing Stock’ album. We saw it very much as an evolutionary thing, rather than a revolutionary thing, which is what we had been looking at before that.

PB : Did you do other things between 1983 when you first started working with Talk Talk and 1991 when it all ended ?

TFG : I always made it my policy to try and do one record between Talk Talk albums, even though Talk Talk albums were exhausting to do and I usually took break after doing them, which was in convention to my previous policy of working back to back. It, however, became more difficult for me to find stuff that I wanted to do. I was okay between ‘The Colour of Spring’ and ‘Spirit of Eden’ , but after ‘Spirit of Eden’ I found it really difficult to find anything that I found challenging enough. Talk Talk records were quite fulfilling. I didn’t really feel that I was desperate to go off and do something else. The one thing I did try and do was go back to doing guitar bands again just to kind of keep myself a bit roughed up. ‘Spirit of Eden’ was only intermittingly rough. I do like a lot of noise really, which is why ‘Laughing Stock’ is a bit noisier. It is because I wanted it noisier.

PB : Which other acts did you work with during this period ?

TFG : I did an EP with Lush and worked with the Catherine Wheel. I did some single projects as well.

PB : ‘Laughing Stock’ was a very tough album to record..Lee Harris and Phil Brown both apparently had to seek therapy afterwards. Did it have a similarly adverse effect on you ?

TFG : It didn’t really. ‘Laughing Stock’ was an interesting and intriguing and challenging record to make, but I had never had this massive psychological overload that the others did. I don’t think that Mark did either. I can understand why Phil in particular did though. It took a long time to record. He was in a darkened room for a year listening to the same six tracks. There are albums that have gone on longer than the making of that one, but it must have been a particularly intensive experience and probably what forced him to have a period of readjustment afterwards.

PB : Was there a feeling once you had done ‘Laughing Stock’ that that was it ?. That was the end of Talk Talk.

TFG : I knew from halfway through ‘Laughing Stock’ that it would be the last album that I would make with Talk Talk. Nothing happened after ‘Laughing Stock’ to make me think again. It was always my intention after 'Laughing Stock’ to go off and produce something else. I am not quite sure whether at the point I had had the thought that I would do what I did, but I felt that four albums was enough.. I felt that that Mark and I had simply run our course. We had had a really good run of making records that constantly pushed things forward. I didn’t see any way of moving further beyond that and I wanted to go. Mark wasn’t happy with that, but he didn’t have any choice. He went away and decided what to do on his own (He released a solo album, ‘Mark Hollis’, in 1998 -Ed).

PB : How do you feel about Talk Talk’s albums now ? Do you still like listening to them ?

TFG : No, I don’t to be honest. I can listen to some of them more than others. The one that I actually have the most problem with is ‘Spirit of Eden’. When I said that to another journalist recently he found it quite difficult to believe, but it is the one that bothers me the most. ‘Laughing Stock’ is abstract and difficult to kind of get a grip on and I rather like that about it. It was recorded in a much more lo-fi way which was a very deliberate policy on my behalf and I like it much better for that. ‘Spirit of Eden’ is a bit too clean for me. It gets on my nerves. It sounds a bit over-earnest to me now. It could do with a bit of humour on it somewhere as far as I am concerned (Laughs).

PB : You moved from that onto another long-standing relationship with another band the Catherine Wheel. You produced their first album ‘Ferment’ and last album 'Wishville'

TFG : They were a good group. They were one of those bands that I worked with in between Talk Talk albums. I did 'Ferment' between ‘Spirit of Eden’ and 'Laughing Stock' .

PB : And you play organ and keyboards on all their other albums in between ? What was the appeal to you of them ? What did you like about them ?

TFG : I thought their song writing was fantastic. Rob Dickinson, their singer, has just brought out a solo album, 'Fresh Wine for Horses' in America and which has made zero impact over here. I am not sure how it is doing over there, struggling I would imagine. I think that Rob is a fantastically under-rated songwriter. It has been a constant state of annoyance to me that he has been passed over, because, although I have disagreed with the presentation of some of the songs, and felt they were rather waylaid by whatever was going on at the time, I have never doubted his songwriting ability at all. I just thought the Catherine Wheel were head and shoulders above the competition and I still do. That was really the draw for me. It was their songs. I really am quite in awe of Rob 's songwriting talent.

PB : Did it take you long after Talk Talk to start composing songs on your own ?

TFG : It was a conscious thing. After Talk Talk I had a rest while I had a sit back and think about what I was going to do and what bands there were around that I wanted to do. I decided that I didn’t want to do any of them and that I was convinced that somewhere there was a record I wanted to make. I just wasn’t quite sure what it was, so I rented a very small hut on an island in the middle of the Blackwater Estuary in Essex. The island was called Osea Island . I went there with a four track and worked out exactly what it was that I wanted to do and how I wanted to sing if indeed I did want to sing because I wasn’t even sure of that.

PB : You had done no singing at all until that stage, had you ?

TFG : No, none at all. It was a completely unknown quantity for me. I thought it quite possible, given I think that 95% of vocalists should probably never have bothered to sing in the first place, that I wouldn't like my voice enough to be able to want to make a record with it. As it was I actually came to terms with it quite quickly. I could see a way that it could work within the music environment that I wanted to create. That was how I arrived at the whole Heligoland aesthetic. It was this kind of a mixture of how I wanted my voice to sound and how I wanted it to sound within the context of the instruments I wanted to put together and how distortion would also play a part in that.

PB : It’s largely a solo project, isn’t it ?

TFG : It is totally a solo project. The only time that I am forced to use someone from outside is when I have a very hard and fast idea for an overdub in which I know only one thing will do. For instance on 'Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie' it was very clear to me that I wanted a sound of a flute here and a violin there. As I don’t play either of those instruments I had to get people in from outside. There is not much that I won’t play. I can get something out of most instruments, but I just wanted on these particular fronts to have proper playing, rather than to play as I do which is a much more chaotic and accidental kind of thing. I don’t get people in except when absolutely necessary.

PB : How long did it take you to put together this new album ?

TFG : It took me a long time, two years That is largely because I moved house into what had been an abandoned mattress factory. I had to clean it up, paint it, and set up my studio in there even though the word studio is being a bit generous. It was just a desk, a rig and all my instruments stuck higgledy-piggledy all over the place.

While it took me two years, I didn’t spend anything like that amount of time in the studio. I did quite take long chunks out of that. I didn’t used to work weekends and I didn’t work for a lot of the summer as well, so that is another reason why it took so long.

With each of my records I always have one disaster and something holds it up. On ‘Heligoland’ it was to do with drumming and on ‘Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie’ the hard drive died just before I managed to back up the whole summer’s work. I lost about thirty overdubs, which was one of the most distressing things that has ever happened to me in my life. I had to go back and redo all this stuff that I was really happy with. The album never recovered from that in my eyes. I never felt the same about it. Once I had lost all that stuff it was only ever going to be a second best for me. Nobody else would spot it, but for me it was really all spoiled. It was never going to be the same again. Until then it was shaping up to be an album that I would actually really like. I have never actually made an album that I have really, really liked.

PB : How do you feel about 'Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie' now?

TFG : I don’t know. I haven’t listened to it. I never listen to anything after I have mixed and mastered it. It is generally far too intense an experience. All I can say is that I have got nice memories of a lot of it in my head. I am still enthusiastic about it because I am a great fan of my own songs. Although some of it consists of second time around performances in which I had to desperately copy sounds that I had got before. I think they are all cool. I think, even after all the problems with it , it is probably a cool record.

PB : Having done most of your songwriting in collaboration with Mark, how did you find starting to write songs for yourself ?

TFG : I found it really liberating. One of the reasons that I won’t go back to production is that when you are working by yourself you can have an idea, however abstract, and not have to justify it and not to have to explain it and not have to try and convince anyone that for the next five days you want to work on this particular route.

I don’t have to do any of that. If I want to spend a week finding a bass sound I can do that. If I want to spend ten days finding the one chord that I can find in my head but I just can’t find on the guitar I can do that. That’s the sort of freedom I can get from working on my own. I get so much pleasure out of dealing with my own little deviations. It is a lot of fun.

It can be very limiting making records for other musicians and for record companies. The record companies, particularly the major labels, want music to tick all the right boxes. Your bass drum has got to be punchy. Your snare has got to be loud. Your guitars have to be bright. Your vocals have to be ridiculously loud. You are forced into a very rigid way of looking at it by the people paying the bills, especially with drums, bass and guitar music, and I found that incredibly limiting.

The idea of never having to do that again is a total liberation for me, Whatever you want to do, you do and there is no one else going “No, I don’t want you to do it like that.”

PB : You were given a lot of freedom with Talk Talk, especially with ‘Spirit of Eden’ and ‘Laughing Stock’. In some ways then is that a continuation of what happened in Talk Talk ?

TFG : Yes, to a degree. I would quantify that though by saying that even with someone that I felt sympathetic with musically like Mark there were still channels that I had to move down. There wasn’t any point in me saying “Okay, let’s go over here” because I knew what would work for Mark and what wouldn’t. Although they were boundaries that I was largely sympathetic to they were still boundaries, whereas Heligoland for me anyway, possibly has no boundaries.

PB : Was it a conscious decision then after doing these big orchestral sounding records with the likes of Talk Talk and the Catherine Wheel to do something more lo-fi ?

TFG : Yes, definitely. When you’re involved in production you’re always working towards someone else’s template, whether it is the band’s template or the record company’s template. People don’t like the idea of their records sounding worse than their demos, using the word “worse” in a very subjective way. For me people’s demos are almost invariably better sounding than their final records. I don’t mean better in terms of their fidelity. I mean better in terms of how interesting, how charismatic, how endearing, how moving they are. Musicians doing demos are more likely to do things off the top of their heads, because they are doing things as the inspiration strikes them rather than copying something and trying to improve on it further down the line when they feel that they have got to accommodate the record company or their listening public. A lack of finesse is really important to me because all it signifies to me is a lack of production, a lack of a barrier between the playing and the listening. I now see production in that respect as being a largely negative thing.

PB : Is that why you started putting “deviced by Tim Friese-Greene” instead of “produced by Tim Friese-Greene” instead on the credits of the albums that you were involved in towards the end of your production career ?

TFG : That was a particular thing for the Catherine Wheel at that particular stage. I only put it on ‘Wishville’, which was actually the last record I ever produced. I said to them I didn’t want the responsibility of the record.As it was largely not mine and as with most of those records I was working to someone else’s template. I didn’t think putting “produced” on it was fair to anybody because I didn’t want the responsibility of something that in the end I might not be happy with. I didn’t want the responsibility of it if it went right, and equally I didn’t want the brick bats if it went wrong, so I thought of “deviced” as being somebody who provides musical devices or mechanical devices to some extent, but which didn’t have that rather Svengali like connotation with the word “producer” which dates back to the 50’s and 60’s. I think it is a complete anachronism these days and that it should be stricken from the record.

PB : You play a five string guitar on both this album and the last album You only started playing the guitar more recently. Why did you decide to play a five string guitar rather than the more regular six string instrument ?

TFG : It actually happened by accident. I broke my G string and I didn’t have a spare. I lived in the middle of the country at the time. I, therefore, simply moved my B string up to be my G string and when I got there I thought “That looks quite interesting” and so I changed the tuning slightly on one string. Then Heligoland was born and I wrote a few tunes on the five string. I can play a six string guitar (Laughs), but I just choose not to because I prefer my tuning. I did normal tuning when I first picked the guitar up in about 1985. I played the guitar at the beginning of ‘Spirit of Eden’, which was the first time I played the guitar on record. Those were the only two chords I could play. I played that with six strings, but that was pretty much the last time I did play with six strings.

PB : Why did you decide to call this new album ‘Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie ?

TFG : It signifies to me the polarization of recording techniques. The very low end is represented by a pitcher or a flask. They are earthenware vessels and, therefore, very primitive. That represents the most basic sort of recording technique that I use. Moxie in contrast is a computer recording language, so that represents the kind of digital age if you like. It is a symbol to me of the fact that the album uses very low ends of technology and then very high ends of technology at the same time.

PB : How do you write your lyrics ?

TFG : I have very strict rules about lyrics, which I insist on adhering to. I have to enjoy singing them and they have to be very singable, They also have to look good on the page. Generally you find that most people’s lyrics fit one of the two categories. I don’t think that most people’s lyrics fulfill both. You either have lyrics that work well as poetry or look good on the page, and they don’t sing particularly well or they sing fantastic, but when you write them down you think “That really is a bit crap.” Both those criteria have to be fulfilled for me to be able to want to keep them. I do take the intelligence of lyrics really seriously. I don’t mean intelligence in terms of using long words. I mean in being able to find a format for lyrics which possibly hasn’t been explored that much before.

PB : One of the things you said in a previous interview is that you still feel naïve as a musician, whereas you feel much more experienced as an engineer. Do you still feel that way ?

TRG : Yes. The important thing for me is to keep moving. I tend not to play many keyboards these days and have probably not been playing keyboards for about ten years. In the same way I think that it is possible that I may not make another guitar album. I am not saying that I won’t, but I think that it is unlikely that I will. I think that it is important to keep the freshness of exploration there. It means that you have to constantly try new stuff out, and for me that means learning new instruments. That is what I meant about naivety. Naivety is a bit of an oddball thing in that it is nothing that really is under your control. You can’t pretend naivety. You either are naïve or you’re not. Naivety can only come with a kind of unfamiliarity with something. There are several ways one can do that of course, but for me the most potent way that one can do that is by simply playing on an instrument that you are not terribly familiar with and that I think is the key for me.

PB : What will you do next ?

TRG : That’s a good question. I don’t know. After the first album I renovated my house and then I started ‘Pitcher Flask and Foxy Moxie’. I may do the same thing this time. I may do some traveling because traveling is the thing I do best after making music. I may travel and then start another album after that, but to be honest I am not really thinking that far ahead and I certainly wouldn’t say that I will definitely make another album, because I am not convinced that I will . From previous experience when I have said that I won’t make another album I generally have done, so I possibly will.

I don’t think that it will be another guitar album though. I have now got tinnitus. You can only really listen to guitar music loudly and it is now so bad that I can’t listen to it as loudly as I would like without making my ears ring loudly, so it is possible that I will go off at a tangent for the next album if there is one.

PB : It is basically a blank canvas at the moment then, is it ?

TRG : Yeah. I think all of my albums are. I was always intending to do ‘Pitcher, Flask and Foxy Moxie’ as a refinement of the first album and to very much tie up between them conceptually. Someone forced me to listen to the first album a while ago, but I was srill surprised at its similarities to the second one. I knew that ‘Pitcher Flask and Foxy Moxie’ would be an extraction of the first one, but I wouldn’t want to do the third album as being an extraction of the second one, in the same way that I said with ‘Laughing Stock’ that “Okay, that seam has been mined down now as far as I want it to be mined down. I want to find something else.” I think that may well apply to the next album.

PB : Thank you.

More information about Tim Friese's musical and production careers can be found at www.heligoland.co.uk

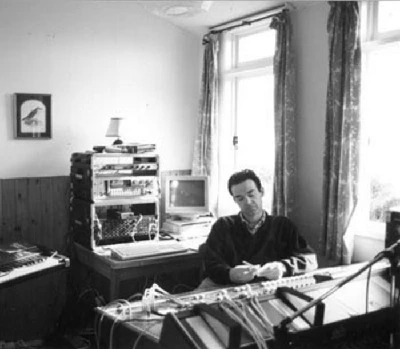

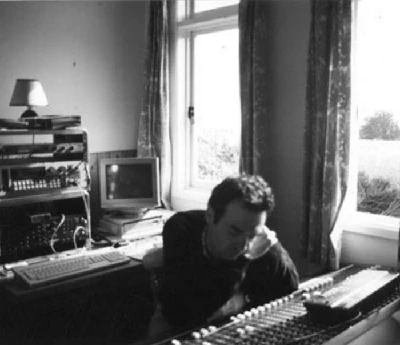

Picture Gallery:-