published: 24 /

12 /

2019

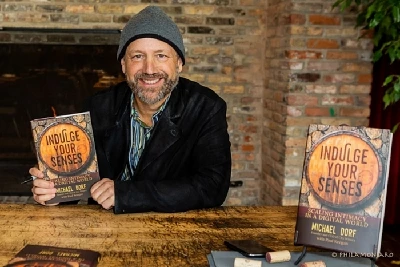

Lisa Torem speaks with American music entrepreneur and venue owner Michael Dorf about operating the City Winery, and his new memoir, 'Indulge Your Senses'.

Article

I’m chatting with the animated Michael Dorf in an all-weather, heated “igloo” at the City Winery Riverfront, as yellow water taxis and hulking, architectural tour boats roll across the sparkling waters of Lake Michigan. It’s no accident that the venue’s view is stunning, the servers are knowledgeable and courteous or that the drinks and sharing platters are of high quality; these variables are part of a well-conceptualised plan.

Comfortably dressed, eager to talk shop, the envelope-stretching exec blends in seamlessly with the brunch-time clientele; not surprising, considering he shares Midwestern roots — Mr. Dorf is from neighbouring Wisconsin.

It’s a busy day, which doesn’t promise to slow down. He’s signing books, schmoozing with employees and reconnecting with old friends. A few feet away, a camera crew awaits. I’ve a strong feeling that the coffee cup he’s sipping from will have to be refilled quite a few times.

In 1986, when still in his twenties, the transplanted New Yorker honed his electrical, plumbing and talent buying skills when he opening The Knitting Factory, located in Greenwich Village, New York. The trendsetting venue boasted an eclectic array of musical styles, but primarily featured the genres of rock and jazz. The list of notable regulars included Lou Reed and John Zorn.

In 2008, Dorf debuted the first City Winery in New York, subsequently adding Chicago, Atlanta, Nashville and Boston to the roster; the common denominator being that each establishment features live entertainment, an on-premise winery and “white tablecloth” dining. A typical “concert venue” “can host up to 200 guests for a seated dinner and up to 300 guests for a cocktail style event” according to the Chicago website. While many major American cities offer fine dining, up-scale bars and concert halls, the idea of housing all amenities under one roof has made the City Winery model unique.

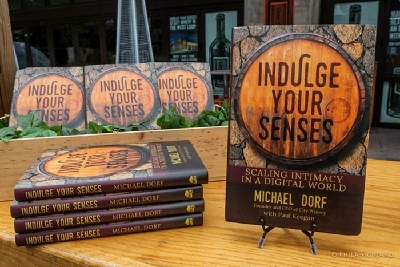

During our engaging in-person interview, Mr. Dorf elaborates on essential points covered in his recently published memoir, 'Indulge Your Senses: Scaling Intimacy in a Digital World' (with Paul Keegan). Read on to discover how his dream of creating a restaurant and urban winery with live entertainment came to fruition, the challenges of running a complex business during the dot.com era and what he learned about sustaining human relationships along the way.

PB: Congratulations on your new book, Michael. Future entrepreneurs and entertainers alike will find your story compelling.

MD: Thank you. I tried to put it in my own voice. My parents had only one real comment - Did you need to curse so much?

PB: As CEO of City Winery nationwide, you’ve had the unique opportunity to nurture and promote live entertainment. That said, what do you look for in terms of professional attitude and talent when you hire an act?

MD: I’m glad you said, “attitude,” instead of, “just liking who you work with.” It’s critical. There can be a great artist who is critically acclaimed and really, really important but if they’re so mean and so hard to work with… Luckily, we have a choice of who we want to work with.

At the same time, I probably think I’m as forgiving about attitude as anyone, but an artist is a creative person and looks at the world differently, communicates differently, not just in the manifestation of their work, but when they’re not on stage, how they deal and look.

We try to give them some leeway, we try to look at that. Shlomo (Shlomo Lipetz), who is at the head of booking now, is pushing this on all of our talent buyers today, that talent is the single most important customer that we have, not that the customer is always right, but we cater. So when looking at artists that we think are obviously appropriate, we want them to be really nice.

PB: Although it may be a financial consideration, are you able to take a chance on up-and-coming artists?

MD: Sure. Giving someone an opening slot is probably one of the greatest gifts we can offer. Now, we don’t always control the ability to put on an opener. The main headlining act, the reason people are buying tickets to the show, they can control and they deserve to have the say, so sometimes they bring their own opening acts; a different market might give it to a friend, you never know, but for us it’s a chance, when the space is there, to give it to someone we like and can’t draw that many people, and hopefully we’ve made a pairing that the audience, that’s there for the headliner, will really love this artist and it’s a discovery for them.

As we’ve been building our new locations after Chicago, we’ve been trying to add a special small room as well, a 150 capacity room - in Boston, in Philadelphia, in New York, that’s being built in Nashville, so we’re looking to have a small room inside which will also allow us space to work on smaller audience artists.

PB: In your recently published memoir, 'Indulge Your Senses,' you discuss the challenge of negotiating tough business deals. That said, what advice can you offer to a business newcomer?

MD: You’ve got to love what you do. You’ve got to be willing to put in the work. Last night in Boston, I gave a lecture to Emerson College students, young entrepreneurs. I love talking to young people to explain that I’m still working my ass off. You know, I’m working really, really hard. That hasn’t stopped. To think that you can pose and position yourself with the idea that you have out of college, that someone is just going to fund it, it’s easy street and you’ll go to the Hamptons for three or four days of the week, that it’s easy, and you’re immediately going to start flying in a corporate jet, that’s just fantasy. It requires a lot of work.

A lot of the stories that I try to put into the book; here’s what I say when I talk to people: I slept on my futon under my desk for almost two years as a way to save money. I needed to do that. I still am working really hard but it’s easier to put in those hours and it’s easier to not look at it as work and almost look at it as play. There’s a philosophy, it’s not mine, but I have always thought along these lines, that you can’t divide a difference between work and play, if you love what you do so much, if you’re in it because you’re waking up and enthusiastic, excited about talking to people, motivating people, designing and developing — if you love what you do, then it’s not really work. It’s something in-between, and at some level in the grey area of between work and play then you can do it all day. You can do it until you pass out.

Seven, ten, eleven hours, that’s a long day. I believe balance is important. I believe exercise and yoga and family and one-on-one dinners and one-on-five dinners, these are all important parts of life that need to be integrated. You can’t ignore that, but how do you integrate it?

Walking out the door at just five o’ clock thinking that the day’s over is just naïve. People keep asking, "How did you find the time to write the book?" I got up and I was excited by the project. I had to weave it into everything else that was going on. It wasn’t like I took a year and stopped working. What’s that saying? When you need to get something done, ask a busy person. Yeah, you can just be efficient with your time.

PB: Was writing the book a cathartic experience?

MD: I think, there was a little bit of catharsis. If I understand the word, it means you’re coming out of the process feeling better, less guilty, whatever. In that sense, I wouldn’t use the word cathartic. I certainly found it to be fulfilling. There was a purpose to it. The purpose wasn’t to make me feel better about being ripped off, in fact, some of the sores reminded me, so it was the opposite of cathartic.

I felt it was important to get down into print some of the stories and some of the lessons for my kids, for students, to learn from what I did. People need to make their own mistakes, but you don’t have to make all of what other people did; hopefully you’ll make your own mistakes and learn from them, but even if the lesson is just to learn to learn from your mistakes that’s a great lesson in itself. People are going to screw up; the key is to bounce back from that, to be able to look at it and go, "What can I do better? What can I do differently next time?"

PB: You talk about the process of creating communities in your venues. Have you come up with a formula?

MD: No. I don’t think we look at it as a formula for community. We understand our job. Our job is to create a venue and a connection between the artist and their fan. We’re trying to create the greatest connection point possible, and if we’re doing that the artists enjoy themselves even more in their performance and the fans enjoy themselves even more because the artist is on top, so it’s truly a one plus one equals three.

Now around that are going to be like-minded people who are excited that there are fellow enthusiasts for that same thing, and in that sense there is a community that has formed around the luxury concert experience or the indulging of your senses around our space. And I love that. That’s a by-product that has come out of it. It wasn’t our intention or our formula of work to develop a tight community, and the community is going to get together outside of City Winery to go upstate and do kumbaya; I think we’ve developed a community but they’re really about fans of City Winery and the overlap is great, but it’s a by-product.

PB: Can you elaborate on the term “enlightened hospitality”?

MD: The running joke these days seem to be, as I finally have a book, that I still sell more Danny Meyer (New York restauranteur) books, 'Setting the Table', than I do my own. Anywhere I go, I promote 'Setting the Table' because I love Danny Meyer’s philosophy of “enlightened hospitality.” Every employee who works for us gets a copy and obviously there’s turnover, so we’re always buying and opening up new places - so I’ve probably bought 3000 copies of 'Setting the Table'. I believe that’s a little more than I’ve sold so far of my book (laughs). That’s just me, one customer, but I’d love it if Danny bought a thousand copies.

If we could be known as the music venue, the music company that has the highest level of service in the business, I feel, that for that alone, I’ve achieved something, so we aspire to be an enlightened hospitality company that uses our philosophy to treat our customers, treat the artists, treat the world with as much white tablecloth as we possibly can.

I would say, the cool thing is that we’ve been able to take that and add just one last little bit of table dust to Danny’s philosophy in that we bring in music and that’s where the “indulge your senses” takes it to another level. We take enlightened hospitality on the service and we pay attention to all the sensory components of the space, and then we add music, which is a sensory element - the live performer just isn’t in typical restaurants. Usually, that is creating this moment where there is a connection for at least a couple of hours between the artist and the fan. If all these other components are working really well, we’ve created a magical evening that will last for a lifetime. And I think we have a better chance in that environment of a live concert with the greatest service, food and sensory to create a magical memory well beyond a regular restaurant experience. And so, take that Danny!

PB: You described yourself as being “still an analogue kid” in 1997. That said, what convinced you to jump on the digital bandwagon?

MD: I’ve always been a new technology/early adapter or a person interested in using the newest tool in order to work. I’m far from a Luddite. We use a lot of technology in what we are doing; our own ticketing system, but that’s to have a better service relationship with our customer, the data we collect so we can better market to our customer. From sound to lights, we’re deep in technology in order to create a better experience.

For the two hours within the space, we really want to be delivering so much of that basic physical, tactile, “atoms” experience, that just can’t be digitised, that just can’t be recreated, no matter how well it’s videotaped, rebroadcast on some 3D goggle plasma thing, it’s just not going to be the same. You can’t digitise wine. You can’t digitise sperm. These are a few things that require human contact and or atoms.

What I figured out with City Winery was I’d gone overboard during the build-up of the dot.com with the Knitting Factory. I was looking at expansion and how to digitise everything. That that was the be-all and end-all. And it wasn’t, and in fact, on some level, I’m going the opposite direction in terms of that experience. I’ve no interest in getting involved in intellectual property rights and having a record company and being a media mogul and all that kind of stuff. I want to create experience.

PB: In your book, you also claim that the record company was at its peak in 1999, but “it turned a blind eye to the new technology.” What should have happened?

MD: There’s no question… Many history books are starting to look at this — the music industry felt they weren’t going to be touched by the online, the new media, that this would be another format that they could control.

I don’t think they anticipated Napster and the aftermath of Napster, which is where kids trade music files and go to YouTube today or pay $4.99 for all-you-can eat music. What that would be like was that they would not be making money from records anymore. The record industry has been decimated. They took a long time to realise that they would be vulnerable to it, but I don’t know what more they could have done.

Apple obviously jumped in quickly. Now with Spotify there are a lot of services, but the artists are still not making any real money from producing their work. They’re using their work to pay attention to them and eyeballs to them - their revenues, a little bit coming from publishing, but mostly it’s from live performance so that’s been a 180-degree switch since I’ve been in the business.

PB: During the span of your career, you have gone beyond achieving the status quo. For example, after establishing yourself as a restauranteur and talent impresario, you went on to study the process of producing your own wine. Can you address the topic of acquiring new skill sets mid-career?

MD: Part of it is a desire to just always be learning and what a luxury that could be. The Knitting Factory was an improvisational business plan. I was flowing with the waters going down the stream. The decision to do City Winery: I had a family, I was using other peoples’ money…

The Knitting Factory was my own money. It was just me. I was a kid. I didn’t have any responsibilities. So if it was a failure, not that I’d be happy or satisfied, but I could have gotten on a plane, flown back to Wisconsin and probably lived at home and found a job. I feel very lucky.

When it came time for City Winery, it was much more calculated, much more serious in terms of a business plan, and I studied it, so the combination of a wine-making facility, an urban winery, with a music venue, while unprecedented on some level was creative, no question, but it was also very calculated in that this would differentiate us completely from Live Nation, House of Blues, over there. I mean, Isaac Tigrett? (American businessman/club owner). A genius. House of Blues had a unique style that was its own. It became a chain and was sold to Live Nation and maybe it’s lost a little bit of that vibe and soul, now that he’s not building them and designing them, but it was a differentiated space.

I took that and went well beyond the idea of differentiation and created a winery, which some people would say is insane, but that really made us very, very different, and I think also added a level of authenticity that today’s society really demands. People want to make sure stuff is for real because we’re living in this Orwellian weird time that our president thinks everything is fake. If we’re going to call ourselves a winery, we want to get into it. It’s not going to be Vegas, insert certain smells into the air, fake it all out. We could do all that, but we want it to be super authentic. That was very calculated.

PB: You discussed the high points of your career, but also your dealings with the “vultures.”

MD: I learned a lot around the mistakes of accepting agreements that I just felt, because I had overdosed on technology I wanted the money, I really wanted to drive the whole deep technology integration into media, and so I accepted things, because, like many of us in the dot.com, we believed that our business would be worth a billion dollars, so it’s okay.

So the venture capitalists, that I like to call “vultures,” were very aggressive in their deals and I accepted that fate. On some level, the Trinity Church lease thing, in the end, our lease always said that there’s a 12-month demolition clause. I had that for the first eleven years. We got a really below market rent and I accepted that. I was a big boy but with that, differently, I was looking into a member of the church’s eyes, who said, "You can have three years, five. Don’t worry about it. We’ll give you two-and-a half years notice. You’ll be fine. "

Or when it came to the renewal of the new lease, the vulture capital deals that I signed, I accepted, but I knew that there was still risk. I wasn’t told, looking into the eyes of the venture capitalists that I trusted, and they didn’t say, “Don’t worry, we’ll never screw you.” Then, I’d feel even worse. These deals pretty much said, “we’re going to screw you.”

The church, on the other hand said, "Look, we’ve got some boiler plate in here that you ought to know about, but don’t worry. We’re not going to screw you. We’re going to give you more notice", but when it came to moving into the new space there was real clarity that we are going to be able to recapture our investment over three years minimally. And that fact that it didn’t happen, that’s where, really for the first time, I had to litigate and we’re in a battle and we still are and it’s wild. It’s so wild, that the day before Yom Kippur, our Jewish law firm received notice that the judge needed to hear oral arguments on the case, finally after six months, the next day on Yom Kippur. Is that a weird coincidence? We did survive. The motions were dismissed so things are looking good for us in this legal battle but it’s the first time I ever had to litigate, whereas the venture capital? I didn’t have any real grounds to litigate so the overall thing i, you really have to keep your eyes wide open. It’s important to know who you’re doing business with.

PB: In terms of philanthropy, can you update us on the Michael Dorf Presents series? In the past, you’ve honored legends such as Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and Simon and Garfunkel. Who else is on the horizon?

MD: At Carnegie Hall? Well, Carly Simon will be coming in March. We’re over 1.5 million dollars in donations to music education. I want to someday look forward to Stevie Wonder. It’s such a fun project to do, to pick your favourite artist, then have the next twenty artists do the favourite music of your favourite artist. The fans love it and it raises a lot of money for charity.

PB: Thank you.

Lisa Torem would like to thank Dan Conroe, Chicago City Winery for his assistance on this article.

Photographs by Philamonjaro

www.philamonjaro.com

Band Links:-

https://www.michaeldorf.com/

https://www.facebook.com/michael.dorf

https://twitter.com/Michaeldor

Picture Gallery:-