published: 6 /

10 /

2010

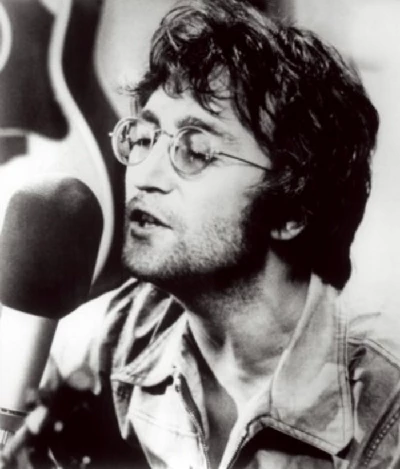

In our 'Soundtrack of Our Lives' column, in which our writers write about the personal impact of music on their lives, Lisa Torem writes of the reconciling effect that John Lennon's songwriting has had at various difficult points in her life

Article

“Here is a song I wrote. A lot of people thought it was about my parents, but it’s about 99% of the parents alive or half dead,” John Lennon says casually, on a You Tube video. It looks as though he’s chewing gum, his face looks relaxed. Looking rock-star cool, wearing blue-tinted glasses and a faded army jacket, he doesn’t appear shaken or victimized by his widely-publicized, broken childhood.

'Mother' was on the album, 'John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band'(1970). I was riveted to the song because I had been exploring my own feelings of abandonment, seeking a self-help treatment or simply a quick fix.

Lennon’s voice is set against a simple, but resounding piano. The lyrics were simple, also, but deep. “Mother, I had you, but you never had me/I needed you, but you didn’t need me…” His voice is extremely child-like at first. His line of “I just gotta tell you goodbye” is also casually performed, but soon his voice emits some raw, grasping tonalities, some almost indistinguishable, unapologetic death rattles.

The song did not come about merely as another album filler. Lennon had been introduced to Arthur Janov’s Primal Therapy, a process which theoretically allowed the subject to return back to earlier states of development when excruciating pain had occurred. Janov’s book, the 1970 ‘Primal Scream’ had garnered the songwriter’s attention in a powerful way.

Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono were prime candidates, but especially Lennon who, at age five, was asked to choose between living with his sea-faring dad Fred and beautiful, spirited mother, Julia. Ultimately, his Aunt Mimi and Uncle George got custody, but Lennon had delighted in spending time with his young, but enthusiastic parent, who was so different in personality than his strict, no-nonsense aunt.

But, sadly, when Lennon was a teenager, his biological mother got struck dead by an off-duty, drunk policeman, steps from his Aunt Mimi’s home. Julia was musical, while Aunt Mimi had warned the young idealist that he’d never make a living playing his six-string friend.

Lennon spent much of his life thereafter trying to come to terms with his overwhelming sense of abandonment and Primal Therapy was a sincere cry for help. But, it also served as a catalyst for some of his most aggressive and emotional balladry. Lennon had once said, “In the therapy you really feel every painful moment of your life.”

Lennon had coined the song, ‘Julia’ for 'The White Album', the Beatles ninth official album in 1968. That was the most haunting song I had ever heard. Always inspired by poetry, Lennon had been moved by the line, from Kahlil Gibran’s work, ‘Sand and Foam,’ which read: “Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so that the other half may reach you.” In ‘Julia,’ Lennon had used this first phrase, and then added: “but I say it just to reach you, Julia…”

Like Lennon, Gibran, was a searcher, writer and painter. He had written this work in 1926. Lennon became an immigrant, of sorts, later moving to America, where his life would be sadly interrupted by the senseless bullet of a crazed fan, Mark Chapman. This time, it would be millions of fans who would feel the desolate sting of abandonment.

I had always been stunned by the beauty of this songwriter’s lyrics. When I first heard him sing, “Here I stand/Head in hand/Turn my face to the wall/If she’s gone I can’t go on…” I was somehow emancipated.

Lennon, a huge Dylan fan, was attempting to capture what he considered that troubadour’s poignancy. But, though I considered Dylan a proficient poet, I was never deeply moved by his works. I was moved by Lennon time and time again, however, and this is why.

When I was growing up, I had a flock of doting aunts and uncles. They would come over and bring heaps of food and tell humorous stories on Sunday afternoons. I was rooted to them; one aunt, who later became a professional comedian, was eccentric, but wildly vivacious.

My grandfather, a tailor, had designed her many period costumes. She owned one which made her look like a 1920’s flapper. She had promised me that someday I would have my pick. She had encouraged me to keep at my piano playing. Being in “the business,” unlike, Aunt Mimi, she told me that I would always “make a living.”

Another uncle had offered to send me to law school later down the road. My parents didn’t have the kind of money that would allow for such an offer. I was stunned, as I didn’t feel I could undertake something that serious at any point in my life, but was still flattered. I felt secure having this roost of elders.

But, when I entered my early teens, some unexplainable rift developed. To this day, I don’t know what transpired, but the three of my mother’s siblings disowned us. When my maternal grandmother died in 1989, I tried desperately to find out where and when the funeral would take place (she had moved to Florida by that time), but no one would return my calls.

I tried to ignore subsequent feelings, but would find this brush with abandonment rearing its head at many turns thereafter. I would go to a party, attempt to forge a friendship, then skulk back into the comfort of solitude; never quite trusting the simplest request of others wishing to know me, never quite understanding the limitations, or the definition of what was required to create an internal pact, as rejection felt so comfortable and undeniably familiar by this point.

During a humanities class, my teacher asked us all to create something original for a project. I was never a whiz at math or science, but had recently bought a second-hand guitar. I wrote a song called 'I Would Rather Be a Loner'. I played it hesitantly for the classmates. My eyes were squeezed tightly shut and my nerves were fever-pitched. I won’t pretend the kids reacted with thunderous applause. They were anxious to get their own projects over and done with, but I survived and received a respectable grade. Mainly, it felt gratifying to come out in the open with my insecurities and self-doubts. I also discovered that music was a guaranteed sanctuary, and I would never be quite that lonely again.

On Lennon’s 'Plastic Ono' album, I found a kindred soul. Lennon’s sense of abandonment was genuine and fortunately, the production was low- tech, allowing for his plaintive voice to fully resonate with loss. Other rockers had performed gritty vocals, but Lennon’s talent was, to me, so much more accessible. Ironically, Lennon never liked the sound of his voice on recordings, and was generally up for vocal over-dubbing. I’m not sure that mattered, one way or another, as it was the sincere quality of his voice, not the layers, which counted most.

When my father died, several years after the infamous 9-11 catastrophe in the States, I turned to Lennon again and 'My Mummy's Dead', the final track on the 'John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band'. “My mummy’s dead/I can’t get it through my head/Though it’s been so many years/My mummy’s dead.” I remember the disbelief I felt while grieving over this man who had been so central to my life.

I walked into a café, the next day, my face wet from the warm tears streaming down my eyes, and witnessed people reading newspapers, ordering coffee and greeting friends at cozy tables. I wanted to scream, “Don’t you know that my father is dead?”

It took months for me to forgive that group of everyday, but clueless strangers. But, after that event, I realized that there is a demarcation for those that have experienced similar grief. It is a line of sand that finely separates those that have succinctly grieved and those who have not. Lennon was the master at illustrating the gravity of that boundary using little more than a stark progression, an honest vocal and a lifetime of isolation.

There are those who have not forgiven the man John Lennon. True, like his own father, some people feel he abandoned his own son, Julian. He rose to fame quickly as a young father and was asked to hide his wife Cynthia and child from the fans at first. Later, when he met Yoko Ono, he hurriedly asked his first wife to end their marriage, doing so in a cruel way.

Yet, in Liverpool, I saw an exhibit put forth by both Cynthia and Julian. It was in honour of John and there was much symbolism about the purity of a single, white feather which had reminded them of their loved one. Cynthia and Julian had obviously moved on and forgiven John and, in her books, Cynthia had confessed that her former husband was a man who had experienced deep pain. Fortunately, for all of us, that pain was poured into his music and resulted in providing closure to fans around the world.

Many fans held candlelight vigils to honour Lennon’s October 9th birthdate. I’m not going to suggest that he was a saint or argue about whether his status as a martyr made his memory more colourful post-mortem than it might have been otherwise. I’m simply grateful that after struggling to piece together segments of my life that were wracked with misery, I found someone to help glue me back together again.

Band Links:-

http://www.johnlennon.com/

https://www.facebook.com/johnlennon/

https://twitter.com/johnlennon

Have a Listen:-