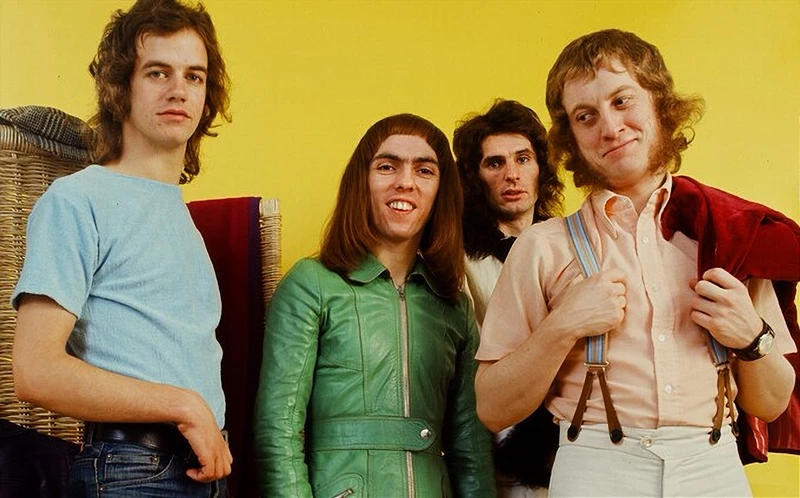

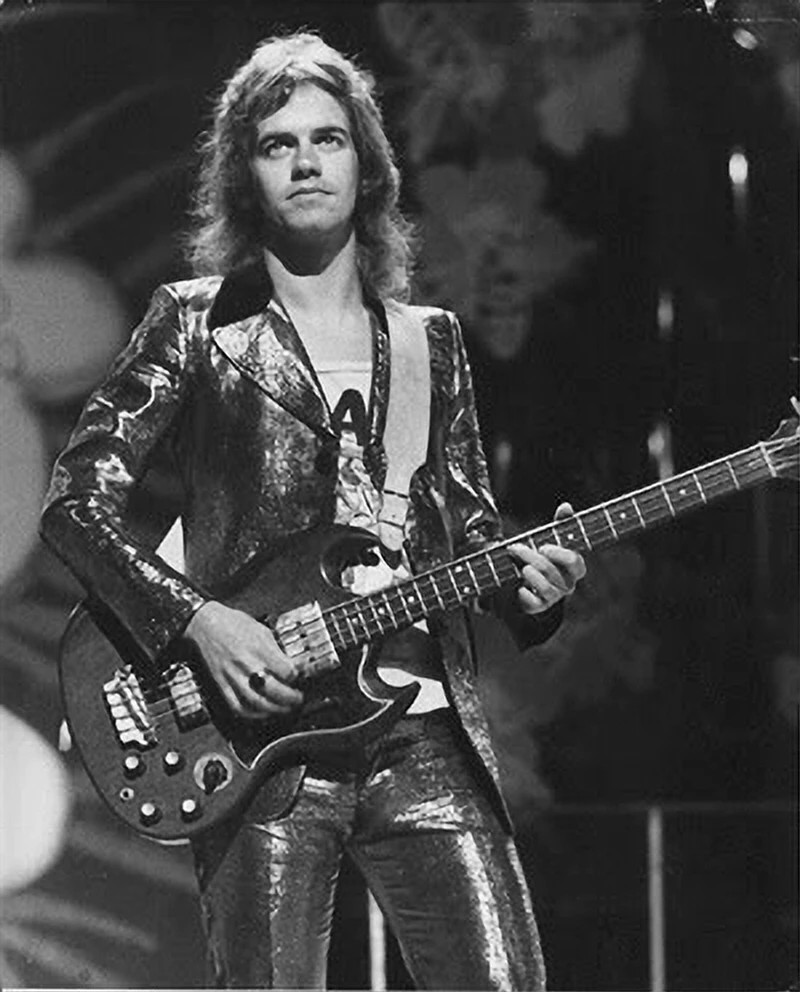

Although he insists he is no architect (despite having essentially designed the house which he still lives in with his wife Louise to this day), James Whild Lea is most certainly the architect of some of the most iconic songs in musical history. Along with Neville John Holder's great lyrics (that’s Noddy to you!), James wrote many of Slade’s greatest hits which still sound as LOUD, as electrifying and as beautiful (We must not forget the many incredible ballads that Slade wrote and recorded such as, ‘Everyday’ and ‘My Oh My’) as they ever have. It is this, alongside Slade’s raucous, edgy and frantic live shows that ensured that Slade would be forever cemented in the Mount Rushmore of rock music, if such a thing existed. An accomplished and virtuosic musical prodigy from a young age, whilst he didn’t realize he was doing so at the time, James even wrote the beginning of what is surely one of the greatest songs ever written, ‘How Does it Feel?', when he was just 13 years old. James’ musical wizardry and versatility in his ability to play so many different instruments is certainly one of the many things that set Slade apart from the rest. There weren’t many rock bands that had a violin player in the 1970s! As the ‘70s ended and the ‘80s began, James formed the rather excellent The Dummies along with his brother Frank. This was perhaps the first time that James had the opportunity to showcase his excellent vocals in his own right. James also ventured into the world of music production and soon found himself as an in-demand producer. James’ recent solo work is nothing short of breathtaking and is a testament to his extraordinary musical talents. His voice is perhaps better than ever before and listeners finally have an opportunity to hear how incredible James’ voice really is. With two Number One songs on Mike Read’s Heritage Chart Show and a brand-new album on the way this year, it’s a great time for the musical genius from Wolverhampton and for his legions of loyal supporters all over the world. Adam Coxon went to meet James and his brother Frank for a career spanning interview PB: I will start by saying that we're here at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, the scene of a recent Q&A that you did with Don Powell, which completely sold out in under five minutes! JL: Two minutes, actually! Two minutes! PB: How does it feel to be so popular after all these years, James? JL: I'll tell you, I don't know about Don, but it seemed to me when we were just walking from the back of the stage to get on the stage I felt lifted. The crowd stood up and everybody started clapping and cheering. It wasn't a riot type of thing, clapping like a football match. It was reverential. That's what it was. So, everybody feels warm and in with it, and we're all here for a reason. It was sort of religious, you know. I'm not religious at all. But, you know, it was amazing. I couldn't believe it. And instead of having the audience coming up with questions, where you end up with a battle going on, who's going to get over the other one, we had Daryl Easlea, the author, as the compere, so to speak. He's written a load of books. I think he's written novels as well. I'd seen him on a Channel 5 programme about the ‘70s and when he was talking about Slade he really knew his stuff, you know, so it was a really big thing to get him to compere it and adjudicate. He got questions from all fan sites all over the world. Daryl asked the first question, “Are Slade going to get back together again?” And Don just went, “No!” Daryl looked at me and said, “What about you, Jim?” And I just said, “It's just another filthy rumour!” PB: Well, I definitely wasn't going to ask if Slade are going to get back together because I'm sure you’re sick to death of being asked that question. It seems that you've only performed a couple of times in your own right since Slade disbanded. I was wondering if you had any plans to do any future live performances? Is that something that you've got any interest in at all? JL: Yeah, the only thing is, as you get older, your voice isn't the same. And also, the fact that I had cancer. It’s 20 years ago since I did the gig at The Robin in Bilston. I got the bass player from Bootleg Beatles at the time and he just turned up and did the gig. We were just going on doing all these numbers like ‘Shaking All Over’ and ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ and the drummer, he also turned up just before we went on. He did a great job though; he was a grand lad as well and I didn't know him at all. I knew the bass player but as we were walking on stage they said, “Jim, we thought we were going to come in here for a laugh. We thought we were gonna be in a pub, up a corner, nobody taking any notice of us.” He said, “We didn't expect a proper gig, A compressed Wembley!” It went so well though. And it's sort of legendary now. There was a guy from one of the music shops in Birmingham who did a bit of roadie work and he was trying to put a plug in at the back through the gig. When he got back to the shop, the guys at the shop asked him what the show was like. He said he’d never seen anything like it. The guys he worked with asked him what he meant. He said, “Well, it was loud.” They said, “Well yeah, we know what loud is. What else?” and he said, “No, there’s loud and then, there’s JIM loud!” He said that he was trying to plug something in at the back of the stage but it wouldn’t go in because of the volume of the sound was shaking the equipment too much! But anyway, it went really, really well. And right to this day, they’re still talking about it. It was 2002, I think. It's just 20 years ago. PB: And other than that, there was 20 minutes that you did in 2017. Am I right in thinking those are the only two performances you've really done? JL: They are. We were intending to do something else, but COVID came. We did a Q&A and I went and played along to these backing tracks too. ‘Jimmy-oke’, I call it! PB: There's footage of it on YouTube and you look like you're having the time of your life. You look great. You sound great. And I think people would just love to see you live again. JL: They would. Who knows what might happen?! PB: Let’s take it back to the beginning. When you guys were growing up, your parents owned a pub in Bilbrook, right? JL: No it wasn’t in Bilbrook! FL: The Grange! JL: No, no, no. There was a posh pub there and it's got rolling lawns. Our younger brother, he says, “James, everybody's always asking me, why were you brought up in a pub with rolling lawns where you could just go out playing and do what you like?” He said, “And we were just in a council house!” Which we all were, actually. So, it became quite a thing. Whoever put that on the internet? I was actually born in a pub just on the ring road here. It was where a pub was but it’s now the ring road. The Melbourne Arms. PB: So this Grange in Bilbrook has nothing to do with you guys? JL: No, there was a pub called The Grange but there’s no connection to our family. PB: Did you grow up in a musical household? JL: Oh, yeah, from birth. My grandad, who I never knew, he died a year before I was born. When the year was coming to pass, and my mum's told me this, my grandmother was hoping I was a boy. We had an older brother, who sadly died from dementia. I was a month overdue and my mum did not have an easy birth with me because I was massive. So, the thing was that, it turned out that I was born on exactly the same day that my grandad died. He sadly died from throat cancer and had a really bad time with it. Then out I popped out and my grandmother and my mum, I think they thought it was like some sort of Jesus Christ, you know. FL: No James, they said, “Jesus Christ!” Ha ha! JL: More like, “Jesus Christ, he’s fat!” So anyway, as I grew up, we moved away from the pub. There was a building here when grandad came back from the First World War, I think it was called the Electric Kinema with a K. But they didn't have all the audio and mobile phones then. So, they used to have an orchestra there playing for the music for the film and my grandad was the lead violin in the Hippodrome before he went to the war. So he went, and he went for a long time. Three years or something like that. As soon as he came back, they sent him to Ireland. He was the leader of the orchestra, the Hippodrome down here, and then they used the orchestra for the cinema. All the uncles and everybody, they could all play. There's my uncle Frank. He could play the piano, the accordion, violin and viola. My grandad played violin and viola. But when the fan club secretary, the historian, found something on one of these ancestry sites and it said Frank Whild Lea. Do you know my middle name is Whild? PB: Yes. JL: So it said Frank Whild Lea has returned from the war and he was the lead violinist at the Hippodrome but he's been asked once again to be the leader of the orchestra at the Electric Kinema and he said he agreed and as he came down he took a standing ovation. And it got on the top, 1920. I thought, bloody hell. You know, so it was the 14 -18 war. So, there must have been a gap somewhere. But anyway, so he took over, and then he went to Northern Ireland. My mum liked music. My dad was a great singer. Our grandmother played the piano. At the grandmother's house, it was always full of music, because the musicians used to come around from the orchestra to see grandad, and they'd have a drink, and then they'd have to play on the piano and the violin. Mum said there was music constantly going on in the house. PB: You joined Staffordshire Youth Orchestra in 1961, and you excelled in your violin exam. JL: Yeah, I don't know why, I didn't practice very much. The beat boom had arrived and I didn't want to be doing Tchaikovsky. PB: So, was that the sort of transition, when you heard rock and roll? JL: I wasn't interested in rock and roll. My older brother Ray got a record player. He was playing it one day and I said, “What's this rubbish?” It was just Bobby Vee and I couldn’t stand it. Then one day I was coming downstairs and there was some music coming up through the floor. When I was upstairs, I could only hear the bass drum. As I walked downstairs, the sound coming from this old Bacolite radio it was ‘Apache’ by The Shadows. Something took me by the neck and said this way! And that was it. That was the moment. It was literally an epiphany. Yeah, it was, being biblical. PB: Were you already starting to experiment with songwriting at this age? JL: No. PB: Not until after you joined The ‘N-Betweens? JL: Yeah. The songwriting came from necessity. I’ve just realized. I got the job for The ‘N Betweens in the same place where my grandad played which I’ve just walked past on the way here to meet you today! PB: Really? That’s incredible! Obviously, I know you're rooted in this area, but I didn't realize we'd be quite so close to places that have been so significant in your life. JL: Yeah. It's over there. We've just walked past where I did my audition. PB: Wow. That’s really amazing! You did the audition when you were 16? JL: Yeah. February. Cold. I'd been in a band called Nick and the Axemen by then. When I was learning to play the guitar, I couldn't go in a pub or anything. I mean, there were bands all over the place playing in pubs and I used to stand at the front of the stage and just watch them. So, they knew I was watching them, so I'm literally just looking. And I was very, very shy and I didn't want to talk to people I didn't know. I was just looking at these guys and I thought, hang on, if I play the lead guitar, people are going to be looking at me, and I don't want that. I thought I'd play rhythm guitar instead. And then the rhythm guitarist in the band I was in left. And I said, “Look, I'll play the bass and we won't have a rhythm guitar. We'll just be like Johnny Kidd and the Pirates.” But when I got the bass, I mean, it was as big as me. I knew that I didn't just want to be playing the bass. I knew I wanted to be a lot more than that. And it got noticed when I did the audition here. I was talking to the singer; Nod wasn’t with us then. His name was Johnny Howells, and he said I could hear the bass going and at first it was ‘Mr Pitiful’ and then he said it was just, ‘WOW!’ PB: What was your first impression of Chas Chandler when you met him? JL: I was in awe of him. As I said, it was the beat boom, and, of course, as it was going on, there were a lot of bands filling up the charts. So, you know, The Shadows were struggling, and, although it was wonderful, they are gods to me, you know, lovely, but it was getting rawer and I liked that. PB: So, you sort of naturally sort of merged into Ambrose Slade, really, didn't you, from The ‘N-Betweens? JL: The singer and the rhythm guitarist left the band. They disappeared and I'd done the audition. I knew I'd done alright and I knew I'd be like nobody else. So, in fact Dave Hill said, “Can we just cool it down guys?” He said, “Hey son, come here.” I wasn't even fully grown. I didn't even look 16. And so, he said, “Come over here. You play ever so fast and I can't tell whether you're bluffing or not.” And I said, “Okay!” He broke a guitar string and Don called me over. He was sitting on the drums. It was just like a movie really. We had an agent up here who knew a guy who was a producer and an arranger and that type of thing and he got an audition with Fontana Records. The boss of the A &R of Fontana Records said,” I want to sign the band.” He said, “I think they're really interesting.” And he said, “They don't need a producer. The bass player can do it.” PB: So you got into production that early? JL: Yeah, I did all the arranging and it got in the newspaper. It said, Jimmy Lea, the youngest producer. Of course, the others didn’t like that at all. I mean, they were three years older than me. In those days, when you’re 16, three years is a lot. I was shy as well. It was a big problem for me. He wanted us to have a London management. And so, he got this guy named John Gunnell. Him and his brother owned the Rickey Tick Club, where Georgie Fame used to play, and John Mayall. And so, he came down, but he was going out with a mate of his which was Chas Chandler, and they both got their wives with them. It was dark and the tables there were low down. It was almost like the old speakeasys. Like a Bogart film. He was talking to me, and I knew he was from Newcastle, but it was supposed to be John Gunnell who was talking to me. And it was me he called over. So, Chas, the last time I ever spoke to him before he died, I said, “What made you sign us?” He said, “I was coming down the stairs, and I turned around to John Gunnell, I said, ‘This is a great version of this record.’” He got in the club and it was us playing.” And he said that he thought, “Wow, if they can do that, they can do other things.”. He said, “I was watching Dave at first and I thought that he’d make a good little pop star, and that he could tell that Don knew what he was doing. And he said, “Then they moved and then I could see you, and I thought, ‘Oh, that's where it's all coming from.’” When we made the film (‘Slade in Flame’), Chas said that David Putnam he wants some sort of theme music for the film. Chas pulled me over to one side and he said, “Would you be able to do some music for the film”? And I said, “Yeah, I’ll have a go.” And we were coming back from the film set and Johnny Steele, who was the drummer in The Animals, he became a fixer for us and a fixer for Chas, a useful bloke. And so I said to him, “Do you know Johnny? I've got a challenge. If I could write something for the theme, for when the film starts.” And I said, “You can tell him that I've got it. In the house that we were living in when I was 13.” There was a rotten old piano that got rained on. It was on an outside veranda. I used to sit in there and I used to pretend I was Paul McCartney and play this piano. I didn't even know anything about the piano. I just got on with it, you know. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I’d written the start of, ‘How Does it Feel?’. I remembered this idea from back then and worked on it and finished it. So when Chas called me on the phone, he said, “Hey, Johnny Steele says you've got the theme.” I said, “Yeah, I've got it. Yeah, we can do it.” And of course, I would imagine of all the tracks we did that that's the one that across the board everybody liked. That was our first number one, I mean it was amazing to have a number one I went over to Nod with my violin and I said, I've got an idea. This was after ‘Get Down and Get With It.’ And so we'd had a hit that had got to number 14. And he said, “Well, what are you coming here for?” We’ve got a hit, and we're done.” I said, “No, we've got a hit now. And we have to keep having hits and I've got something that I think is going to be another hit.” And he was very reluctant to let me into his council house. I said, “Oay, if we're not playing next week on Tuesday, I'll come back and you can do the lyrics,” and that became ‘Cuz I Luv You’. And I think it was that right around the time Marc Bolan was around and it was like ‘Hot Love’ and we wanted it to sort of creep along as well. We were just lucky. Well, we all know what happened after that. So I used to write the songs. I used to take them to him. And I said, “this is what we'll do. I'll write the songs. But I'll always have some lyrics. And then you finish it off.” And it worked really, really well. But we had to keep it coming, you know? PB: Surely you must have felt under an enormous amount of pressure at the time to keep churning out hit after hit after hit, which you were doing, but to have that in the back of your mind must have been difficult. Wasn't there a period where Chas was particularly pressurizing you to churn out these hits, or you churned out one that he didn't particularly like? JL: Yeah, I did feel under pressure to keep coming up with hits but I didn’t have a problem with Chas as he liked everything I wrote. PB: What were your experiences of America? JL: We'd been in America for a long time. We were playing with ZZ Top and The Allman Brothers who were the big thing back then. So, we decided we were going to try and ‘do’ America. And so, we tried to sound more American. PB: So you were trying to constantly adapt your sound for the market at the time? JL:Yeah. We did America and it's funny, you know, the ‘Slayed ‘album. I think that was in the American chart for about three and a half years. Right down the bottom, the album chart. But there it was. And the last interview I ever did with Malcolm Dome from ‘Kerrang’. all he wanted to do was to tell me that you know what's going on in America. I said, “I don't know what you mean. I hated America. I don't want to go back there ever. I don't want to get on a plane ever. Not ever again.” But he said, “All the young bands over there are all listening to Slade” PB: You guys have influenced so many band. So many bands have cited Slade as an influence. Kiss, Nirvana, Motley Crue, The Pistols, The Clash. The list goes on. I don't know how to describe it, but the sound of Slade seems very rooted up here. I don't know if that's just because of the characters in the band, but the sound feels very Black Country or Wolverhampton somehow. I don’t know how else to qualify that. But you read stories and you hear stories that you never wanted to stay in London. You always wanted to come back. I guess it was the same when you went to America in the mid -70s. You didn't really want to stay there. JL: No. FL:Can I just put my tuppenny-worth on that? The sound of Slade, this is from the beginning. Dave and Nod had what I called a manky guitar sound but it worked. It was unique. But when the band broke up, me and James did some recording together. PB: Was this The Dummies? FL: Yeah, And I played the drums and then James played the guitars and the bass and that. And I said to James, “What does this sound like?” This was the only the only rehearsal we did. He said, “It sounds like me and you playing.”. I said, “No. it sounds like Slade” and I then said, “Take the bass out.” And he took the bass out. So, a big portion of the sound came from this power bass going off. Of course, there was Don there as well, you know, but a big portion, it was as clear as possible. Take him out of the equation and it was a good band. Put him back into the equation, and the whole thing changed. And I proved it. PB: Yeah, not many bands had violin players. JL: There was, what was that one in the 60s with Darrell Way and Stewart Copeland. PB: Oh, Curved Air. They’re incredible. They’re still playing. While we're on the subject of the sound, I read one quote from Steve Jones from The Sex Pistols, who said simply, the reason that Slade were great is because they never compromised. I thought that was a great thing to say. JL: He's a big fan, isn't he? PB: What a great legacy, though. JL: Big fan, Steve Jones. Oh, yeah, he's a big fan, yeah. PB: Yeah, what a great thing that you've done it on your own terms. I thought that was great. FL: James came up with a good line to do with that, which was true actually. It was when Slade had all the hits, people then started copying all the records and sounding like Slade, and then James said, the thing is, everybody all sounded the same, so Slade had to find something to move on to. JL: It happened with The Beatles as well. I did have a conversation with Paul McCartney. He wanted to talk to me, I didn't want to talk to him, I felt a bit overwhelmed, to be quite honest. But we were talking and I said, “How did you write so many songs?” And he said, “Well. of course, John was doing it as well, you see, and George was doing it as well.” And we started to talk. This was four years after John Lennon was killed, and we were all in this studio together. Paul McCartney was making ‘Goodbye to Broad Street’ and he wanted to ask me about ‘My Oh My’ and he said he thought it was a tremendous album and a great record. You don't hear it on the radio very often but when you do it's like Lancasters coming over you. So, I said to him, “I know that you and John fell out.” He said, “It was funny, James. We were great mates right from middle through the teenage year, but I spoke to him againnot long before he died and I told him there's this band who are like us, man, like when we were number one all the time.” And he said, “Have you heard them over there?” and John said “Yeah. They sound rough. Really rough. Like we were but rougher.” PBM: Incidentally, we’re a couple of weeks away from the 40th anniversary of the release of, ‘My Oh My’, which I think is a criminally underrated Slade song. JL: Well, Paul liked it! He said, “James, you’re a great songwriter. You’re better than me!” I said, “Course I’m not better than you! Look what you’ve done! You bloody took the world over! You and that other bloke!” Paul was overly complimentary about my songwriting. He said, “Do you want to come over to my house sometime?” I said, “We’ve gotta do this album,” and we were going to America but there was a lot of things wrong. I was ill. The first time was alright when we were in New York but the second time we were in Los Angeles and we did not fit in at all. They just didn’t get it. I was ill and I had to go home. So, everybody went home. Then the time came to go back again. Ozzy Osbourne had got his band together because of the Randy Rhodes thing and the first show was Cow Palace, which is just a great big building. PB: In San Francisco? JL: Yeah. The crew got the equipment set up and it just wasn’t right somehow. The guy from the label was called Tony Scottie. He’d ring me up. It was always 9:15 at night. I couldn’t work out why he’d always call me at that time. He said, ‘”Jim, you wanna come over here? We got it all set up. It’s gonna be a massive tour with Ozzy etc.” I bought a cottage which was very, very tiny and I said to Lou, my wife, “This is gonna be no good, We can’t buy this.” She just said, “No, let’s buy it.” So, we bought it and I designed a house! It was making ‘the’ house into something different. Basically, it was smashed to pieces. I’m not an architect or anything. I’d written a couple of songs. ‘My Oh My’ and, ‘Run Run Away’. ‘My Oh My’ got to Number Two and it was ‘The Flying Pickets’ who held us off the Number One spot. ‘Run Run Away’ was also a Top Ten hit in the UK and I think it might have got top 40 in America. I like the songs. PB: Yeah, great songs! So you guys decided to form The Dummies in 1979. Was this just because you wanted to refocus on the music? As you were saying, Frank, everyone that was coming out at this time was starting to sound like Slade, and you just wanted to work on your own thing? FL: No, the idea was, I used to say to James, because they had such a unique sound, everybody knew Slade when they came on. People were missing how good the songs are. And on the albums, there are some great tracks. I said, “They're never going to be covered, because it always sounds like Slade, and a lot of people can't see past that.” So, I said, “Why don't we do an album with Slade tracks? So that people can hear the song without Noddy screeching down the vocals and we'll do that.” And it worked. It was when we had ‘When the Lights Are Out”, it would have gone a lot further but it was record of the week on Radio 1. And it was in the radio charts for three and a half months, wasn't it? JL: Yeah, the DJ Paul Burnett made it his record of the week and they kept it on the playlist. You know, we were getting there, weren't we? FL: I was an ideas man but I didn't know how distribution works. And that's how we sort of missed the boat a bit. Well, I got PRT (Pye) to bring it out but we'd missed the boat. And then the same happened with when we did, ‘Didn’t You Use to Use to Be You’. That was A listed on Radio 1. Every single show 24 hours a day was on. But I'll tell you now, that that wasn't bad distributions. Chas Chandler, I had a fist fight with him by the way. I lost! What had happened, that should have been a top five record or even a number one I mean the press were well behind it. What had happened was we brought it out and straight on the A list and Radio !. All the commercial stations jumped on it because they follow Radio !. So, I phoned James and said, ‘”Okay James, the first day sales were great’” Then the next day it did whatever it did, and it was all going in the right direction and there was a fucking bank holiday, so we missed the day’s sales. When it came back the sales went down to like 10/15 a day. So, I phoned BMG, spoke to the head of sales, and I said, “I's Frank here. What's going on? We've gone over a week. We're losing the record.” He said, “We're not selling it anymore.” “What?! What you mean you're not selling it anymore?” He said Chas phoned us and said he's got a Slade record coming out and he doesn't want this to get in the way. JL: He fucked it up. FL: But if I’d have turned around to Chandler and said, “Chas, will you manage this?” then he'd have agreed because then he would have got the glory and the ego, but he couldn't see me coming from a village having a top five record. PB: Did Chas have that much sway with BMG at the time? FL: Chas? Yeah. I mean, he bought Jimi Hendrix over here. PB: I know his track record was pretty good. JL:You know, Chas says this, and that’s how it went. FL: So he phoned up and he took it off. There wasn't a new Slade record coming out soon at all but he used that excuse just to get rid of it. PB: Well, didn't you guys own a record label called Cheapskate. Did that not cause a bit of friction at the time? FL: Well, the way that it works, we had Cheapskate Records because it was all done on the cheap. I mean, even James would be there and he'd be loading the car with records in the rain, down to the pressing plant. But it's all great fun, isn't it? It's all brilliant fun. Chas became a 50% partner in Cheapskate because he had Barn Records, or ‘Bomb Records’, I used to call it. Never had any radio play, never had anything. But we were making quite a name for ourselves with Cheapskate. Naturally, there was some animosity towards Chas after he fucked it up with us for The Dummies. The way it worked was Chas had to come in with 50%, He wasn’t too worried about James but he didn’t want me to over shadow him. And then the deal was, whoever bought a record in, kept the majority of the money. Well, of course, we were working together, and it started going really well for us, and that's when Chas started fucking things up, because he’d have got nothing,besides financial, He wouldn't have got any credit, nothing. The ironic thing was there was a Japanese company I went to see. I don't know what they were called now. They were publishing from the record company and I had a few meetings with them about The Dummies. I gave them the cassette of the album and they came back and they said, “Can you come in the office?” I went back down to the office and they said, “We’ve heard back from the record company and they said that they think this is absolutely brilliant.” They wanted us to go over to Japan. They didn't want us to be a band. They wanted us to be a cartoon band like Gorillaz, but this was years before Gorillaz. A fictional band around the tracks. They said, “Can you come over and we'll talk and we'll work a deal out and all that?” So, I turned around to James and said, “James, you never guess what?” I explained to James what had happened. At the time Slade were taking off again and James said, rightly so, I suppose from his point of view, he said, “Frank, I've got a day job. I'm in Slade. I can't just go to Japan when I'm writing again.” There was an obstacle all the time with anything we did. That idea would have been brilliant in Japan. So, we were way in advance to Gorillaz if that had happened. But there was always an obstacle. PB: Tell me about the now legendary Slade performance at the Reading Festival, James. JL: When we got there, Chas pulled me to one side and he said he didn't know how the gig was going to go because it was the ‘New Wave of British Heavy Metal.’ I have got to tell you when we arrived there, there was the caravans where all the bands would get changed to walk on the stage. And it was quite a warm day, it was sort of dusty, and there was traffic going down between there as well. And the four of us were walking down. It was like Clint Eastwood walking out at the OK Corral! Everybody's going, “Look at that. Is that Slade? Are you Slade? Fucking hell! We thought you'd died! So we were at the stage, and Tommy Vance, who hated us when we were skinheads, said, “Hey guys, there's a real buzz out there. You weren't on the adverts, but everybody's up for it. Word’s getting around.” So, we went on the stage and it sort of went quiet, you know, and we were plugging in. And then Tommy Vance introduced us, “Ladies and gentleman, get your stomping boots on. Of course, this is Slade!” You know, typical American type thing. It was alright at the beginning, but then it began to build a momentum. The crowd were going bonkers. And by the time we came off, Chas was on the side of the stage, Frank was on the side of the stage. They both had got tears in their eyes. PB: Really? JL: Well, you know, it's like the movie, but it was real. Dave Hill didn’t want to do it. He thought we were going to get booed off, which we didn’t. Reading really broke us into the field of rock. We wiped the floor with everybody else. PB: Wasn't it sort of really supposed to be your farewell gig? JL: Yeah. PB: And then obviously the reception you got, sort of made everybody stop and think, hold on. JL: Well, it's legendary now. Def Leppard went on after us. I was ever so sorry for them! They got ‘canned’ off the stage! PB: Where did the ‘Therapy’ album come from after all those years? JL: ‘Therapy’. I started writing songs that deliberately didn't sound like Slade, but I wanted to have some philosophy in there. PB: Your voice sounds great on that album. JL: Well, thank you for the compliment! I told Brian May about it, and the next time I spoke to him, he said, “I heard your ‘Therapy’ album, and I didn't like it. I just didn't like it.” He said, “But I liked Dead Rock UK’”, which mentions Freddie. He said Freddie would have loved that. With ‘Therapy’, I had to do some bits that were like Slade. So, it ended with this big raucous thing. I wish I hadn’t put that on the end. Even that was about therapy though. It was about a crooked psychotherapist. In midlife, I started psychotherapy. And then I went to psychotherapy college in the inner circle of Regent's Park. I did really well there. They didn't want me to go, but I did. I wrote a song on the ‘Therapy’ album, about Keith Moon. “I want to go, I want to see four miles. I want to go over the moon. I want to lean up a leg. I want to stay in bed.” PB: Congratulations on having two Number One’s in The Heritage Chart with ‘The Smile of Elvis’ and ‘Universe’. They’re both incredible tracks and I love the videos you’ve made for them. The original version of ‘Universe’ came out not long before Slade split up, right? JL: When it first came out we went to Germany, Holland and Belgium with it and appeared on TV shows out there that were similar to ‘Top of the Pops’. It’s a song I’d always really loved but I wanted to do a brand-new version of it and I think it came out pretty good! PB: You’ve recently been recording with The N-Betweens again as well? JL: Yeah, only one track. We're thinking of doing another one. We're going to do’ Move Over’ by Janis Joplin. We did a great version of this with Slade and we’re not exactly sure how we’re going to approach the new version that we’re going to record together. PB:: When’s your new album going to be released? JL: We’re trying hard. The album is done, it’s all ready. We’re just fine tuning the tracklisting. My grandson came into the piano room yesterday and I was playing bits of the new album and he said, “Who’s that grandad? Don’t tell me it’s you?! I think that’s fantastic!” FL: It’s a strong album. There are no fillers on it. James doesn’t do fillers! It’s got to be out this year. JL: After everything, I’m glad I can be my own man. It's a really nice thing. PB: Thank you. Special thanks to Frank Lea. Main photograph by Adam Coxon.

Band Links:-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Lea_(musician)https://www.facebook.com/JimLeaMusic

https://www.facebook.com/Sladeforlife

Play in YouTube:-

Picture Gallery:-

Visitor Comments:- |

| 5466 Posted By: John Barker, Leeds on 24 Jan 2024 |

|

What a brilliant interview. In-depth and factual. Great work.

Kind regards from John, admin of 'Slade Are For Life - Not Just For Christmas' Facebook page and social media accounts, which fully supports Jim, and all members of Slade...

https://www.facebook.com/Sladeforlife

|

| 5465 Posted By: rob mowlam, Dorchester on 23 Jan 2024 |

|

great interview but we know wyy don wont work with dave would be nice if jim would say why he wont work with him. jim was always the brains behind the music that matched noddys voice. would love to see jim do a live show with a proper dvd made of it.

|

| 5463 Posted By: Chris Selby, Aldridge on 23 Jan 2024 |

|

Excellent interview. Thank you . I'm the "historian" who gets a mention . I am also admin on Jim's official Facebook page . Come and join in the fun . https://www.facebook.com/JimLeaMusic

|

intro

Slade violinist and multi-instrumentallst James Whild Lea with his brother Frank Lea talks about his career with the 70's rockers, working with legendary manager Chas Chandler and his and Frank's underrated other band The Dummies.

most viewed articles

current edition

Screamin' Cheetah Wheelies - Sala Apolo, Barcelona, 29/11/2023 and La Paqui, Madrid, 30/11/2023Anthony Phillips - Interview

Difford and Tilbrook - Difford and Tilbrook

Rain Parade - Interview

Oldfield Youth Club - Interview

Autumn 1904 - Interview

Shaw's Trailer Park - Interview

Cafe No. 9, Sheffield and Grass Roots Venues - Comment

Pete Berwick - ‘Too Wild to Tame’: The story of the Boyzz:

Chris Hludzik - Vinyl Stories

previous editions

Microdisney - The Clock Comes Down the StairsHeavenly - P.U.N.K. Girl EP

World Party - Interview

Michael Lindsay Hogg - Interview

Ain't That Always The Way - Alan Horne After The Sound of Young Scotland 2

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

Dwina Gibb - Interview

World Party - Interview with Karl Wallinger

Barrie Barlow - Interview

Joy Division - The Image That Made Me Weep

most viewed reviews

current edition

Marika Hackman - Big SighSerious Sam Barrett - A Drop of the Morning Dew

Rod Stewart and Jools Holland - Swing Fever

Loves - True Love: The Most of The Loves

Ian M Bailey - We Live in Strange Times

Paul McCartney and Wings - Band on the Run

Autumn 1904 - Tales of Innocence

Roberta Flack - Lost Takes

Banter - Heroes

Posey Hill - No Clear Place to Fall

related articles |

|

Slade: Interview (2019 |

|

| Slade's classic hit 'Merry Xmas Everybody' inspired hordes of fans much to the hard-working band's delight. Nick Dent Robinson speaks with lead guitarist Dave Hill about its success, the group's 80's reformation and his autobiography. |

Pennyblackmusic Regular Contributors

Adrian Janes

Amanda J. Window

Andrew Twambley

Anthony Dhanendran

Benjamin Howarth

Cila Warncke

Daniel Cressey

Darren Aston

Dastardly

Dave Goodwin

Denzil Watson

Dominic B. Simpson

Eoghan Lyng

Fiona Hutchings

Harry Sherriff

Helen Tipping

Jamie Rowland

John Clarkson

Julie Cruickshank

Kimberly Bright

Lisa Torem

Maarten Schiethart